Journal of Interpretation Research

Volume 23, Number 1

Every Kid in the Woods: The Outdoor Education Experience of Diverse Youth

Aracely C. Montero

Nina S. Roberts

Jackson Wilson

San Francisco State University

Lynn Fonfa

Golden Gate National Recreation Area

Author Note

This study was made possible by the wonderful support of the education and interpretation staff at Golden Gate National Recreation Area, especially Education Specialist Lynn Fonfa. Thank you to the Department of Recreation, Parks, and Tourism at San Francisco State University, specifically Dr. Nina Roberts and Dr. Jackson Wilson. Finally, thank you to all the teachers who assisted in making this study possible—their help has been greatly appreciated. This paper is based on Montero’s graduate Applied Research Project. For more information contact Aracely Montero, Aracely_Montero@nps.gov; (415) 289-1832.

Abstract

The purpose of this qualitative study was to evaluate the experience of underserved fourth-grade students participating in the National Park Service’s Every Kid in a Park (EKIP) initiative through the Into the Redwood Forest (IRF) education program at Muir Woods National Monument. The project’s aim was to understand the experience of underserved diverse students (i.e., race and ethnicity, gender, and Title I schools) participating during the 2015–2016 school year. The study included six teacher interviews and document review procedure of 60 student journals. The findings reveal that the EKIP exposed students to parks, the inquiry-based learning proved effective for outdoor learning, and the impact of the nature experience encouraged environmental stewardship. Implications and recommendations for further implementation of both the EKIP initiative and IRF at Muir Woods are discussed.

Keywords

Every Kid in a Park, Muir Woods, experience, diversity, education

Every Kid in the Woods: The Outdoor Education Experience of Diverse Youth

Mature trees are growing in the woods

All trees are growing tall and growing cones

Tall trees drop cones, cones drop and drop seeds

Up in the sky sun shines to the trees

Running water through streams

Each person pass through pick up trash that they see

Tall old trees fall knock down other trees

Rain starts to fall, small flower grow in the green ground

Each tree drops seeds

Every tree is happy in Muir Woods

—Haiku poem by fourth-grade student, Class 6, Journal 7

Youth of color traditionally have been underserved in natural spaces, such as national parks (Outley & Witt, 2006). The limited presence of racial and ethnic minority populations in national parks prevents youth of different backgrounds from having meaningful and powerful experiences in nature. The U.S. Census Bureau claims by 2020 more than half of children in the nation are anticipated to be non-white (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). According to Jarvis (2016), the future of protected natural spaces is dependent on the growing diverse population; national parks will not continue to thrive and garner public support if underserved youth remain without meaningful experiences in nature. Outdoor education programs, such as Parks as Classrooms programs within national parks, have been around for decades working towards engaging diverse youth through hands-on outdoor learning (Kiernan, 2012). The expected growth in the number of youth of color will require an increase in services and programs, and a rethinking of how they are designed and presented (Outley & Witt, 2006). For the new generation to experience America’s great outdoors, the Every Kid in a Park (EKIP) initiative was established for fourth graders and their families to experience national parks free of cost (White House, 2015).

In 2015, President Obama asked for a $45 million budget increase from Congress for youth engagement across the Department of the Interior; $20 million was dedicated for bringing one million fourth graders from underserved communities to their local parks and waters (McGrady, 2015). The EKIP initiative committed to giving every fourth-grade student from a diverse background a free pass to federal lands and waters for one year from September 2015 to August 2016. According to the White House (2015), the goal of the EKIP program was to connect youth of all backgrounds with the great outdoors. National parks play an important role in supporting EKIP through their Parks as Classrooms curriculum-based outdoor education programs.

Established in fall 2015, EKIP is a relatively new initiative. Therefore, gaps exist in research about the program’s outcomes, especially the experience of underserved youth participating in Parks as Classrooms programs. While the National Park Foundation has taken the initiative to collect and evaluate quantitative evidence to support their 2015–2016 Park Field Trip Grant Program, there has been no qualitative evidence reported about the experience of underserved youth participating in EKIP. This current study, with multiple sources of qualitative data, was conducted to understand the experience of diverse fourth-grade students participating in EKIP (i.e., race, ethnicity, gender, and Title I schools). The data reveal information about the experience of students and impact of the IRF program at Muir Woods National Monument.

Muir Woods National Monument (Muir Woods), a unit of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA), supports Every Kid in a Park through a Parks as Classrooms grant-funded program, Into the Redwood Forest (IRF). Muir Woods was established in 1908 and is home to one of the last remaining old-growth redwood forests near San Francisco (GGNRA, 2016). The Coast Miwok indigenous tribe resided in the San Francisco Bay Area near Muir Woods for over 10,000 years and used the land for hunting, fishing, and gathering (GGNRA, 2017). Today, Muir Woods is a distinct national monument visited by hundreds of thousands of people each year (Auwaerter & Sears, 2006).

In 1992, the National Park Foundation (NPF) and the National Park Service (NPS) jointly launched a national education initiative called Parks as Classrooms (U.S. National Park Service, 2003). The NPS-funded initiative was a call to action to raise awareness of the intrinsic value of national parks to student learning through interdisciplinary hands-on programs and stewardship-based project learning (U.S. National Park Service, 2003). Parks as Classrooms also shifted program focus from traditional environmental education to curriculum inquiry-based programs embedded in the natural and cultural resources of national parks (National Park Foundation, 2001). Parks as Classrooms at GGNRA uses an inquiry-based curriculum that includes the Understanding by Design framework, California Common Core Standards, Next Generation Science Standards, and History-Social Science Content Standards.

IRF is a curriculum-based outdoor education program that welcomes approximately 1,000 students from Title I schools in San Francisco, Marin, Contra Costa, and Alameda counties (L. Fonfa, personal communication, September 25, 2014). IRF is made possible by the collaboration of three organizations: Muir Woods National Monument, Save the Redwoods League, and The Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy (L. Fonfa, personal communication, September 25, 2014). In 2015, the NPF also provided considerable support for the implementation of EKIP at Muir Woods through the Every Kid in a Park Transportation Grant, which aims to remove this barrier for underserved and urban communities to accessing public lands and waters (National Park Foundation, 2017).

The IRF program concentrates on the relationship between culture and lands of the redwood forest. The program’s inquiry (e.g., guiding) question is: How do living things thrive in their habitat? Furthermore, IRF includes the following three elements: 1) Pre-visit lessons facilitated by the classroom teacher and NPS staff—emphasizing redwood ecology and the cultural history of Coast Miwok, 2) A three-hour field session in the woods led by NPS staff, and, 3) Post-visit lessons in which students demonstrate their understanding of what they learned. Students carefully document the classroom lessons and field sessions in the IRF student journal, a hard copy booklet supplied by the NPS. Overall, students delve into approximately 12 hours of redwood-focused activity, with an additional four hours of study for teachers that attend a preparatory workshop. At the end of every IRF field session, each participating fourth grader receives an EKIP voucher they can exchange for an EKIP pass at the national park of their choice. NPS staff distributes a voucher to each student, explains the intent of the EKIP, and encourages students to return to Muir Woods and/or other national parks to deepen their experience.

Literature Review

Outdoor education programs deliver opportunities for youth to experience nature in a personally meaningful way. Participation in outdoor education programs nurtures curiosity, improves motivation and attitudes, and engages youth through participation and social interactions (Brody, 2005). Spending less time outdoors can lead youth to experience negative effects on their life. For example, Louv (2008), who coined the term nature-deficit disorder, claimed that modern youths’ lack of time spent outdoors resulted in a wide range of behavioral, health, cognitive, developmental, and spiritual problems. The EKIP helps mitigate this nature-deficit disorder by “ensuring every (underserved) American has an opportunity to visit and enjoy outdoor spaces” because “more than 80 percent…live in urban areas…and many lack easy access to safe outdoor spaces” (National Park Service, 2015).

Experiences of Youth in Outdoor Education Programs

Learning in nature teaches about environmental problems, biodiversity, and environmental action as manifested in environmentally sound behaviors, and helps develop ecological appreciation in nature (Brody, 2005). Furthermore, Scott, Boyd, and Colquhoun (2013) identified that participants experienced elevated levels of motivation and interest in learning about nature, developed and improved relationships with nature, and reinforced positive attitudes towards environmental issues.

The need for more structured nature-based learning experience is partially caused by increases in urbanization and less than half of racial and ethnic minority youth who live in urbanized areas have not had prior experiences in nature (Aaron & Witt, 2011). They identified the following student perceptions toward nature: freedom, excitement to be in nature, fear, perception that nature increased healthy behaviors, and increased intentions for stewardship (Aaron & Witt, 2011). Previous research supports the thesis that outdoor education programs can facilitate positive learning outcomes for youth, and such organized educational experiences may be especially critical for urban youth (Aaron & Witt, 2011; Brody, 2005; Scott, Boyd, & Colquhoun, 2013).

Underrepresented Youth in Outdoor Education Programs

Outdoor education experiences are often costly and difficult to access, especially for racially and ethnically diverse students with fewer economic resources (Larson, Castleberry, & Green, 2010; Paisley, Jostad, Pohja, Gookin, & Rajagopal-Durbin, 2014; Tardona, Bozeman, & Pierson, 2014). Economic barriers, misogyny, and racism have contributed to outdoor spaces in America being primarily for the recreation and education of white, economically privileged, masculine, and able-bodied individuals (Paisley et al., 2014; Warren, Roberts, Breunig, & Alvarez, 2014). Despite findings that diverse youth benefit from outdoor education (e.g., Paisley et al. 2014; Tardona, Bozeman, & Pierson 2014), youth of color often have fewer opportunities to learn environmental concepts through primary experience in nature (Larson et al., 2010). Additionally, research shows experiences in outdoor adventure education do not include a diversity of students and can be profoundly isolating at times (Paisley et al, 2014).

Inquiry-Based Learning in Outdoor Educating

Inquiry-based learning is defined as a “question-driven learning process involving conducting scientific investigations, documenting and interpreting narrative or numerical data, and summarizing and communicating findings” (Wu & Hsieh, 2006, p. 1290). The learning process highlights active participation and responsibility to discover new knowledge (Pedaste, Mäeots, Siiman, de Jong, van Riesen, et al., 2015). The inclusion of inquiry-based learning in outdoor education is important because it allows students to experience meaningful learning in nature while creating awareness of the natural environment around them (Rozenszayn & Assaraf, 2011). According to Marx, Blumenfeld, Krajcik, Fishman, Soloway, Geier, and Tal (2004), inquiry education can be successful among urban students as long as it includes culturally relevant knowledge and relates to beliefs held by youth from diverse backgrounds. Coupled with inquiry-based learning, culturally relevant pedagogy offers an effective approach in outdoor education because the students’ prior knowledge and prior experiences help frame the program design and delivery.

Evaluation of Curriculum-Based Outdoor Education Programs

Evaluation is essential to measure the value and quality of the EKIP programs, especially for undeserved communities. According to Thomson, Hoffman, and Staniforth (2003) the evaluation of outdoor education programs is critical because “a good evaluation program can improve program quality, improve student learning, and ultimately assist the program to achieve its goals, which may include such things as a higher degree of student involvement and benefits to the environment” (p.16). Furthermore, Monroe (2010) maintained that the goal of most outdoor program evaluation is to make judgments about the value of programs to decide improvements, marketing, expansions, and changes for the program. According to Monroe (2010) evaluations need to answer the difficult questions of: Why is the program successful? and, what factors describe the success? Evaluation is fundamental to understand further how to implement curriculum that is inclusive and relevant for students of color who participate in EKIP.

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the experience of the fourth-grade students who participated in Every Kid in a Park through the Into the Redwood Forest education program at Muir Woods National Monument. The primary research question was: What are the experiences of underserved fourth-grade students who participate in the EKIP program? The experience of traditionally underserved diverse students (i.e., race and ethnicity, gender, Title I schools) was investigated during the 2015–2016 school year. Specifically, the study included seeking responses to: What were the value, meaning, and impact of youth experiences in Muir Woods? What were the learning outcomes during their experiences?

Methods

A qualitative design with multiple sources of data was used for this study. Data included individual interviews with fourth-grade teachers, as well as entries from student journals. First, teachers were interviewed to elicit their perceptions of students’ experiences and learning outcomes. The interviewer used an open-ended approach, opening the door for a holistic view from the educators of their perception of student experience and learning outcomes gained from IRF (Brannen, 2005). Their altruistic assessment is central to the study since teachers are the adults with the most ongoing contact with the students through facilitation of the curriculum, observations of students in the field, and coordination of post-visit demonstrations of learning. Subsequently, an analysis of student journals more directly assessed the students’ experience.

Sample

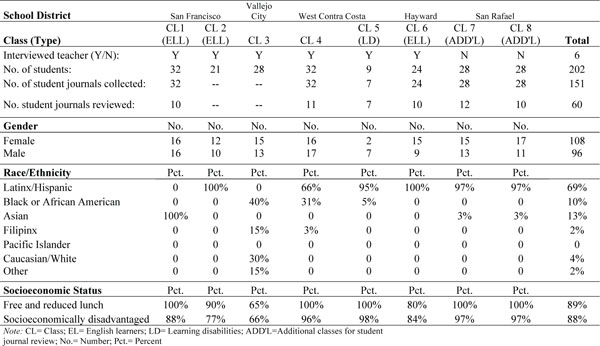

The fourth-grade teachers and students that participated in this study were from local Bay Area elementary schools in the cities of San Francisco, San Rafael, Richmond, Vallejo, and Hayward (see Table 1). Six individual teacher interviews were conducted. Teachers were purposively selected by using the following criteria: classes from Title I schools and/or at least 80 percent free and reduced lunch, new and experienced IRF classroom educators, English Language Learners (ELL) educators and non-ELL educators, schools from different geographic areas within the Bay Area, and schools that already had an established relationship with Muir Woods.

The Title I program provides financial assistance to schools with the highest numbers of students from low-income families (U.S. Department of Education, 2015). The educators interviewed teach in five school districts: two from San Francisco Unified School District, two from West Contra Costa Unified School District, one from Vallejo City Unified School District; and one from Hayward Unified School District.

A total of 151 student journals were collected from six independent classes associated with the interviewed teachers and within the same school districts as previously noted. The one exception was the student journals from a San Rafael city school were obtained in place of the journals from Vallejo City Unified School District because Vallejo programs occurred before journal collection began for the study. Journals were selected as follows: Each journal was reviewed for completeness of content; the student name was intentionally omitted from the analysis to avoid gender bias; and from 151 journals, a sample of 60 journals that were considered complete (i.e., legible, pages not left blank) were randomly selected.

Demographics of the student journals were 53% female and 47% male; 69% Latinx/Hispanic, 10% Black or African American, 13% Asian, 2% Filipinx, 4% Caucasian/White, and 2% Other. Ten student journals were selected from each class for analysis for a total of 60 student journals reviewed for analysis. Each set of student journals was labeled Class 1 through 8 (see Table 1).

Although journals from Class 7 and 8 were reviewed, the teachers of these classes did not participate in interviews. Those two teachers did not respond to multiple attempts to contact them via phone and email so they were omitted from the interview process. Despite lack of participation by two teachers, student journals from San Rafael City Schools from these classes was included due to their active participation in the education programs at Muir Woods and their geographic location. This is one of the only school districts in Marin County that includes Title I schools.

Conversely, instructors from Class 2 and 3 participated in interviews but did not supply any student journals for review because their program occurred before journal collection began for the study. Journals were collected for research purposes between December 2015 and June 2016 and Class 2 and 3 attended programs from September 2016 to November 2015. It was originally intended that 10 journals would be selected from each class for review; however, Class 5 only returned seven student journals with sufficient content (i.e., journals that were not legible or pages left blank). Therefore, additional journals from two other classes (11 journals from Class 4, and 12 journals from Class 7) were selected to maintain the total of 60 student journals for review and analysis.

Table 1. Participant Demographics from Teacher Interviews and Student Journals

Table 1. Participant Demographics from Teacher Interviews and Student Journals

Procedure

During the first phase of data collection, individual teacher interviews were conducted at six elementary schools from October 2016 to December 2016. The purpose of these interviews was to gather data about teachers’ perceptions of students’ experiences and learning outcomes. An open-ended teacher interview guide was designed based on Thomson, Hoffman, and Staniforth (2003). Two scripted interview questions included: “What do you think was the most and least enriching part of your students’ experience during the education program?” and “After completing the reflections and post-site activity, what do you think students gained from participating in the program?” It’s important to note that teachers were not asked if students “lost” anything due to participation in the program. This was debated by the authors in the design of the study; however, it was decided that it was unlikely there would be any loss associated with participation. To partially address this issue, the primary researcher was sensitized to this concern and followed up on both positive as well as negative outcomes mentioned by the teachers during the interview.

Five interviews were conducted in person at each school location and one was conducted over the phone. Each interview was 30 to 45 minutes in duration. At the conclusion, teachers were given time to ask questions and invited to contact the primary author if they had any further information or insights to share. As participant incentive, teachers received a token of appreciation from the Muir Woods gift shop.

The teacher interviews were conducted one year following their class’ participation in the program (at the beginning of the 2016–2017 school year). This time frame was intentional including goals of reflection yet this may have affected the results of the interviews. For instance, some teachers had a difficult time remembering everything about their students’ experience from the previous year, yet many did have clarity due to the uniqueness of the program.

Student journals were collected from fourth graders who attended IRF between December 2015 and June 2016. Students were unaware there was a study being conducted and therefore unaware their student journals would be returned to Muir Woods. The journals included pre-lessons, field lessons, and post-lessons. Towards the end of each field visit at Muir Woods, students were tasked to write reflections regarding what they learned and experienced during their visit. After each visit, teachers conducted one of two post-site lessons to reinforce student learning: 1) Students completed the following statement in their journal: After my visit, I think I can…in a redwood forest, because…, or, 2) Students wrote and illustrated a poem that shows the life cycle of a redwood tree. Educators were provided with pre-stamped envelopes to return completed IRF student journals and post-site lessons to the primary author.

Data Analysis

The teacher interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and then analyzed. A thematic-based content analysis was utilized to code and determine common themes and patterns of the interviews and journals to deduce replicable and valid inferences from the text (Krippendorff, 2004). The text was read and re-read a second time and research memos were developed. Based on these memos, emergent codes were developed (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

The memos and emergent codes were debriefed with the GGNRA education specialist. Although both the primary author and the education specialist were part of the GGNRA educational program, the education specialist was not directly involved in the program delivery nor the data collection. Therefore, the coding process included perspective of the primary author directly involved in programming and data collection, as well as an ancillary perspective based on program knowledge yet less involvement in the program delivery and research process.

The modified emergent codes then were compared to the research questions and grouped into major themes. This coding structure was then applied to the texts to connect the words and images of the teachers and students back to the questions (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008).

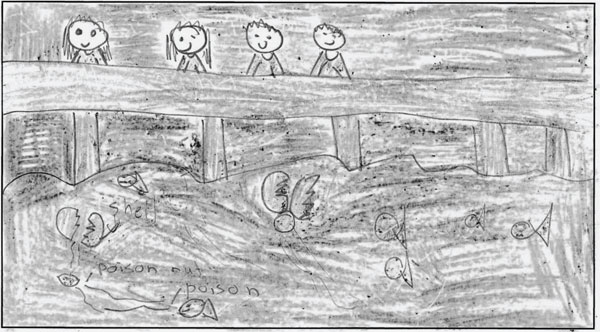

Figure 1. Student drawing illustrating how Coast Miwok people thrived at Muir Woods

Figure 1. Student drawing illustrating how Coast Miwok people thrived at Muir Woods

Results

The results derive from two sources of qualitative data, teacher interviews (TI) and student journals (SJ). Five themes emerged: 1) Exposure to National Parks and Nature (TI&SJ), 2) Impact of Experience in Nature and Stewardship (TI&SJ), 3) Learning in Nature (TI), 4) Program Enhancements (TI), and 5) Feelings about Nature (SJ). A description of each common and specific theme, and a representative quote or image, is presented to further illustrate the themes.

Common Themes

Two common themes emerged from both sources of data. Although the results focus on the commonalities between the two sources, there were some issues within each theme that were unique to the interviews or student journals.

Exposure to National Parks and Nature. All six teachers claimed that one of the most enriching parts of the education program was bringing students to their national park for the first time. Teachers stated that for many of the students, joining an IRF was an introduction to places outside of their community. The exposure to a natural place like Muir Woods was especially unique for many students. Teachers expressed that traveling to national parks outside their immediate community is nearly impossible for many of their students’ families. It was only their participation in IRF that made Muir Woods an attainable destination for the students and the adult chaperones who accompanied them.

Another reason why this field trip is really special for a lot of students, especially with our demographics. Our school is in the heart of Chinatown, and it’s really hard for their parents to travel or take them to a place like Muir Woods—across the Bay. So, having this experience, I think that just itself is icing on the cake for a lot of the students. —Teacher, Class 1

The results from student journals corroborated with the interview data. When students were asked to write reflections about what they learned and experienced, many students conveyed it was their first time at Muir Woods and/or “it was my first time to see the redwood trees” (Journal #6, Class 1). They also communicated this as being the “first time going into the wild” (Journal #3, Class 1), suggesting that this was their first time in a relatively pristine environment outside their community.

Students were exposed to hands-on knowledge about redwood ecology and cultural history that otherwise would have not occurred without their participation in IRF. Students’ description of what they learned during their experience at Muir Woods, included concepts related to redwood ecology and the cultural history of Muir Woods. When asked to journal about park aspects they were exposed to during their first visit to Muir Woods, they described “bugs, fish, trees, plants, banana slugs, [and] fungus.” Forty percent of the student journals described their pleasure in experiencing the forest for the first time as reflected in the student quote below:

Today I learned things that I would have never learned in my life! I would never known that new redwood trees can grow out burls. I also seen many things that I have never seen in my life such as the tannic acid from a redwood tree. Thank you so much! I hope I’ll see you again! —Journal #4, Class 1

Students also typically explained learning about how redwood trees thrived (e.g., tannic acid or burls) and/or expressed how Coast Miwok people connected with the land using natural resources. The reflections completed at the Muir Woods at the end of the program included students writing or drawing what they learned. The post-site lesson (completed back in their classroom) for which students composed a poem encouraged them to creatively give voice to what they had learned by writing acrostic or haiku poems and drawing pictures. Figure 1 is an example of a student drawing (completed at Muir Woods at the end of the program) illustrating what the student learned about how the Coast Miwok people thrived in the redwood forest by using the buckeye nut to fish in creeks.

Teachers and students also confirmed IRF contributed to their awareness of the EKIP initiative. When teachers were queried of their awareness of the EKIP, four out of six teachers replied that they did not learn about EKIP until their students participated in IRF. All six teachers verified the education program helped make students more aware of EKIP and the park system; for example, “…the awareness of what the park system is, where it is, where the different locations are, and some of the programs that are there, you know…that sense of belonging” (Teacher, Class 6).

All six teachers substantiate the notion that if it weren’t for IRF, students would not have been informed about EKIP, and would not have known to pursue a free voucher. One hundred percent of the students who participated in IRF received a printed EKIP voucher and were encouraged to return to Muir Woods to exchange their vouchers for an official EKIP pass. Students wrote about how they wanted to return to the park because they now had passes. Their involvement in IRF produced a sense of belonging in the park since they realized that they could return free of cost with their special EKIP pass. Teachers shared that they hoped the vouchers would inspire students to tell their families and friends to return to Muir Woods or other national parks. All six teachers relayed that they knew of at least one student in each class returned to get their official pass. Parks that teachers reported students visited with their EKIP pass included Muir Woods, Yosemite, Yellowstone, Fort Point, and other unnamed national parks.

Impact of Experience in Nature and Stewardship. The data suggest that students’ stewardship attitudes may have resulted from their experience at Muir Woods. The sample of teachers interviewed proclaimed the visit to Muir Woods impacted students desire to have future experiences in nature. Educators proposed that the inquiry-based learning at Muir Woods motivated students to be more curious about nature at school and in their community. Three of six teachers expressed that students brought their redwood curiosity back to the classroom. For instance, students proceeded to want to research the redwood ecology and the cultural history of Muir Woods, or made connections between what they learned in the program to other science lessons in their classroom. Furthermore, teachers claimed the visit to Muir Woods invigorated students to have more interest in science and even realize they liked science, in general.

Some of them realized that they like science more, I mean by being out there (Muir Woods). I noticed on the bus ride back…he’s (referring to a student) looking around and it seemed like he enjoyed it out there…. I was in the group with him too (at Muir Woods), and he never raises his hand and he raised his hand in class to share (about Muir Woods). So, it was just nice to see that they got that experience and that it’s perking their academic interest. —Teacher, Class 4

Data from both teachers and students suggest that, for at least some students, as they become more revitalized in the nature setting, they started to lose their fear of nature. Teachers articulated that before the trip to Muir Woods, they noticed some students displayed fear about interacting with nature but, after the visit, they observed students were more comfortable. Consequently, students indicated feelings of overcoming their fears of nature in the student journals.

Students outlined conquering their fears through descriptive phases such as: “I can be brave in the woods” (Journal #3, Class 7); “banana slugs are not gross [anymore]…” (Journal #6, Class 7); and “I am strong! I am Tarzan!” (Journal #3, Class 4). The design of this study does not allow these comments about courage to be directly connected to those students that were more fearful before the experience. However, it does suggest that overcoming fears of perceived danger from the natural world was part of the experience of at least some of the students. All students who proclaimed conquering their fears, also described wanting to care for the environment around Muir Woods. Hence, hinting at the beginning of stewardship principles became clear.

Today I learned to hug trees and more about redwoods trees! I learned not to touch bad things because I want to stay safe and carefree. I learned about to not keep trash on the floor, because if we do then animals will probably die. Help other animals! —Journal #2, Class 4

When teachers were asked to formulate what they thought students gained from their experience at Muir Woods, many answered with ideas related to stewardship. Teachers expressed that students left Muir Woods with a deeper understanding of why and how to care for nature. A couple of teachers suggested that students left the forest with more insights as to why it was important to have natural places like Muir Woods. Similarly, when students were asked by rangers to share what they learned at the end of their visit to Muir Woods, many wrote about how they learned to care for nature. Words used in response to this final writing prompt included “respect,” “protect,” “important,” “special,” and “take care” of elements of or a more generalized concept of nature.

Some students responded to this final writing prompt by describing the importance of minimizing anthropogenic pollution that negatively impacts the health of animals and degrades the environment. Students came up with the following descriptive phrases to report how they could care for the environment: “Today I learned, how animals are important…when people throw trash they come out and eat the trash, they are not supposed to…they can die (Journal #7, Class 4). Furthermore, some even discussed their thoughts about the human impact on nature and the value of redwood trees, “After my visit, I think I can make a change in the redwood forest and I can make my life and animal’s life better. Play and treat others the way you want to be!” (Journal #11, Class 4); “Today I learned that humans need to take care of the forest and national parks” (Journal #10, Class 7); “After my visit, I think I can take care of the trees because I want more green plants living” (Journal #2, Class 6). These quotes, and other data from journals, suggest that at least 50 percent of students left the forest expressing empathy for nature and/or understood some ways how humans could impact nature. This suggests that students’ attitudes towards stewardship and knowledge of some conservation behaviors were developed as part of the IRF program.

Furthermore, the journals demonstrated that multiple students wanted to share their knowledge about the forest with others. For example, “After my visit, I think I can teach my brother about what I learned because I learned it in my field trip” (Journal #12, Class 7).

Specific Teacher Interview Themes

Two themes were unique to the teacher interviews: Learning in Nature and Program Enhancements. These themes offer insight into the effectiveness of EKIP through the IRF curricula and teacher recommendations for program enhancements.

Learning in Nature. The teachers discussed the effectiveness of learning in nature through their students’ involvement with the IRF education program. Learning in nature was the focal point for many of the educators. They pointed to the ability of learning in nature as the most effective way for students to comprehend science and experience a natural setting through a new lens. All six teachers stated that nature education gave students an opportunity for hands-on experiences. Four out of six teachers proposed that the IRF curriculum was effective due to the direct relevance with the California State Content Standards. They also stated that IRF provided Title I students with an important opportunity for applied natural science, because many times natural science was the subject they are forced to overlook due to state testing:

That the opportunity to have science because in all honesty the pressure’s so much on language arts and math of our schedule although it’s written into our schedule - It’s science and social science...the first thing that gets pushed away. —Teacher, Class 4

Three of six interviewed taught students who were English Language Learners (ELL), students who are unable to communicate or learn easily in English. ELL teachers declared that IRF was enriching for their students because of the bilingual curriculum, bilingual student materials, and bilingual park rangers who taught the program in different languages (Spanish and English). A fourth-grade ELL teacher asserted the following: “having the bilingual rangers and curriculum was very great that I put that as a high priority for making the program enriching” (Teacher, Class 6).

The teacher interviews also revealed that learning in nature was most enriching due to the program’s focus on interactive student engagement throughout the program. The IRF program supports inquiry-based learning and stimulates students to engage in place-based inquiry science and historic investigation of the cultural history of Muir Woods. During the interviews, teachers repeatedly acclaimed the importance of inquiry for students.

Going into the forest… the questions that came out of them (students), which just really amazed me and it kind of carried over back to the classroom and other areas as well. They got more curious…but just that spirit of wanting to investigate and having interest and being active with finding things out. —Teacher, Class 3

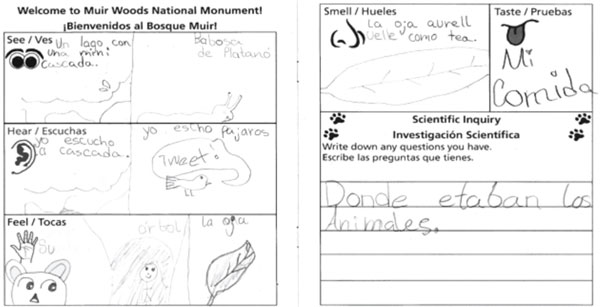

The inquiry-based learning sparked curiosity and motivated students to want to take part in future inquiry at school. Additionally, teachers mentioned it was beneficial for students to take part in nature through a sensory experience. During the Muir Woods visit, students were engaged in learning by writing or illustrating what they saw, heard, felt, smelled, and tasted. They were encouraged to ask questions throughout the field lessons (see Figure 2).

Teachers expressed that the sensory experience helped students connect more with nature. For example, using their hands to feel the leaves, trees, and bugs allowed students to directly engage with the environment. Teacher interviews suggested that this was specifically helpful for the ELL students whose first language was not English, and the special education students who had a difficult time reading and writing.

Figure 2. Student Journal – field notes (Note: IRF student journal field notes by fourth-grade student in ELL class. Field notes are in Spanish. Left side top to bottom translations: a lake with a waterfall; a banana slug; I heard a waterfall; I heard birds; a tree; a leaf. Right side top to bottom translations: the bay laurel leaf smells like tea; my food; where are the animals?

Program Enhancements. When educators were asked to determine the least enriching aspect of the IRF program, they suggested one pre-site change and two changes to the forest immersion experience. One of the most common areas for improvement was the vocabulary lesson. That is, teachers are asked to review vocabulary words prior to the NPS classroom visit and Muir Woods field trip. They stated the vocabulary lesson was confusing and not interactive enough for students. Teachers advised for the lessons to be more visual and hands-on by including illustrations of each vocabulary word or including lessons that have students act out the vocabulary word. Second, the Coast Miwok culture lesson also was identified as needing enhancement. Teachers confirmed it was difficult for students to forge a connection between the cultural history and ecology of the park by stating the following, “the connection between what we learned about the Coast Miwok should be more evident in their (forest) experience” (Teacher, Class 6). Finally, teachers expressed that more time in the forest would allow students to engage in a longer outdoor/nature experience and, therefore, form a closer connection with the environment of Muir Woods.

Specific Student Journal Themes: Feelings about Nature

There was only one common theme that emerged from the student journals: Feelings about Nature. Students aired positive feelings about their experiences in the redwood forest. Common words students used to express positivity included “fun,” “awesome,” “good,” “wonderful,” “beautiful,” “safe,” “carefree,” “cool,” “love,” “special,” “calming,” and “stress-free.” Students wrote and illustrated poems that conveyed happiness while learning in the forest, “Muir Woods Nature (title of haiku poem); Muir Woods is peaceful; It is calm and wonderful; It is beautiful” (Journal #3, Class 7).

Many of the poem words and illustrations students put in their journals describe a high level of comfort during the novel experience in an old-growth redwood forest. However, it was not surprising to learn that some students brought an internalized fear of nature. Although students confirmed overcoming their fears, many still pointed to being scared. Students affirmed their fears by using the following language in their student journals: “a little scared,” “the forest felt really scary,” and “the forest is a dark and creepy place.” Findings indicated that students who harbored fears also described uncomfortable thoughts: “it was cold” and “being in the forest makes me feel worried and nervous.” A student even indicated being uncomfortable because of what they think they might encounter in the forest: “After my visit, I think going to the woods was fun because there’s a lot of exploring and a little scary because I think there are clowns in the woods” (Journal #6, Class 4). However, although students expressed fear of the forest, most students expressed positive feelings about their experience in Muir Woods.

Twenty percent of students communicated wanting to return to Muir Woods. After the experience in the redwood forest, students were asked to write about what they could do at Muir Woods. Some recorded phrases such as, “After my visit, I think I can come back to Muir Woods again, because I got a pass for a whole year” (Journal #7, Class 7). One of the main reasons some students of color wrote about a desire to return was because they received their EKIP vouchers to visit free of cost. They used reinforcing language to express their feelings of wanting to return to the park, “I hope I can return” (Journal #7, Class 7) and “I felt that I wanted to go back” (Journal #6, Class 6). Data from journals suggest that receiving EKIP vouchers made students feel welcomed to the national park and stimulated a desire to return to Muir Woods.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand the experience of underserved fourth graders participating in an Every Kid in a Park (EKIP) program through the Into the Redwood Forest (IRF) education program at Muir Woods. One of the primary goals of EKIP was to bring youth of color to their local national parks and waters. This is the first qualitative research focusing on the experience of racial and ethnic minority students participating in EKIP programs nationwide. The data from the student journals and teacher interviews suggest that these diverse students who participated in EKIP through IRF had authentic natural experiences appearing to increase their knowledge of natural places and national parks. Additionally, teacher interviews suggest that using natural places effectively enhances student learning about natural science and cultural history.

Affective Learning Coupled with Inquiry

Learning in nature contributed to the meaningful experience students formed during their participation in the IRF program. Teachers claimed the IRF curriculum effective because it was also inquiry-based pedagogy that satisfied the California State Standards. The access to quality hands-on natural and social science lessons were perceived as especially valuable because science is sometimes considered sidelined due to incentives for schools to focus on increasing or maintaining student scores on standardized exams. The process of inquiry-based learning offers students an opportunity to “…develop meaningful understandings and construct scientific explanations by exploring the natural and scientific phenomenon” (Wu & Hsieh, 2006, p. 1289). Overall, teachers were satisfied with the hands-on learning that took place in nature and confirmed it allowed their students to have meaningful, inclusive learning experiences in the redwood forest.

Intersection of Cultural History and Natural Science Curriculum

The IRF Parks as Classroom program includes both the cultural history of indigenous Coast Miwok and the natural science of Muir Woods. Coupling these two disciplines with open-ended questions is a characteristic of inquiry-based learning that allowed students to connect their experiences in the program with previous knowledge. This intersection differs from other outdoor education programs that focus solely on natural science and fail to equate the subject to students’ everyday reality.

While acknowledging the existing strength of the program to help students connect the learning in the program to other areas of their life, interviews with teachers suggest this aspect could be further extended. Teachers recommended more culturally relevant lessons that stimulated students to think about their own traditions to develop a deeper understanding and historic empathy for Coast Miwok. According to Patchen and Cox-Peterson (2008) culturally relevant pedagogy (CRP) is contingent upon respect for student thinking, prior understandings, and active learning. Furthermore, Patchen and Cox-Peterson (2008) stated that CRP “depends not only upon recognizing students’ experiences (Nieto, 1994) but also upon teaching to and through those experiences, while connecting them to broader social contexts” (p. 997). Including more culturally relevant curricula would strengthen student connection with the natural science of Muir Woods.

Student Knowledge and Attitudes about Nature. Students expressed both feelings of comfort and fear towards their experience in the redwood forest. The data suggest that positive feelings helped students shape a promising steward ethic toward nature. For instance, multiple teacher interviews confirmed that some students’ stewardship attitudes and behaviors increased after their experience. According to Brody (2005), learning in nature inspires “environmentally sound behaviors” (p. 605). The perceptions of insecurity some students expressed towards spending time in the redwood forest may have been related to having prior “scary” images or an ignorance of what to expect (Aaron & Witt, 2011).

The positive valence expressed by students further illustrated a desire to spend more time in nature. Students expressed feelings of wanting to return to Muir Woods. This intention was supported by a desire to use their “free pass.” It is outside of the design of this study to know how many acted on their desire to use their free pass and acquire a “free pass”; however, it is known that 1,391 fourth graders did acquire a free pass in the 2015–2016 period as obtained from the Muir Woods database. Further research is needed to know what the rate of acquisition is for students similar to those in this study, communities that have traditionally been underserved by the National Park Service.

Intentions of Every Kid in a Park. EKIP at Muir Woods exposed underserved youth, specifically racial/ethnic and low-resourced youth to nature (e.g., from Title I schools). This helped fulfill the goal of EKIP to connect youth from underserved and low-income communities to national parks (National Park Service, 2015). Teachers recognize that the majority of their students would not have enjoyed an opportunity to visit their national parks without participating in IRF. The EKIP pass only removed one economic barrier that discourages these students and their families from visiting national parks and other wild areas.

During the interviews, multiple teachers claimed that although the IRF program exposed students of color to national parks and made students aware of EKIP (e.g., voucher), transportation, food, and other costs associated with visiting national parks were likely to continue to prevent many families from using the passes.

Figure 2. Student Journal – field notes (Note: IRF student journal field notes by fourth-grade student in ELL class. Field notes are in Spanish. Left side top to bottom translations: a lake with a waterfall; a banana slug; I heard a waterfall; I heard birds; a tree; a leaf. Right side top to bottom translations: the bay laurel leaf smells like tea; my food; where are the animals?)

They get to the (EKIP) card, you can go anywhere (parks), but for a lot of our parents and families, how do you get to these places? Well, you know it’s good to get in there (parks), but I (the students’ families) also have to consider…to have to eat somewhere. You have to pay for gas, etc. —Teacher, Class 2

Therefore, further research is needed if students from diverse communities, such as the ones in this study, acquire their passes at lower rates than students from more affluent communities. Yet beyond just knowing if there is a difference, new research must result in greater understanding of the strength and pervasiveness of the constraints causing students from such communities to acquire their passes at a lower rate. Additional programs to increase access to national parks and other public lands, such as the EKIP program, need to consider how to ameliorate transportation, or other constraints, that reduce participants from using “free passes.” Otherwise, such programs may simply provide a benefit to families that would have already visited the parks and merely provided an incentive for a small portion of non-visitors to visit natural spaces.

Results from this study reveal experiences in the IRF program were overwhelmingly positive. However, it is possible that such short-term experiences simply expose these students to what could potentially be difficult for them to experience later on. This phenomenon could theoretically lead to a level of dissatisfaction yet, again, further research is needed.

Limitations

The researcher’s direct involvement with implementation of the IRF education program may have had a direct influence on the study results. The first author is the lead park ranger of the IRF education program and the education programs manager at Muir Woods National Monument. Emergent codes were developed and, subsequently to help mitigate bias, professional feedback was obtained from the GGNRA education specialist to determine reliability of coding categories and themes. Second, the lead researcher had prior relationships with all the teachers who participated in the interviews. Because of this, participants may have answered questions based on social desirability. However, this limitation was addressed prior to the interview by stressing to the teachers that their answers would not affect future participation in IRF education programs. The teacher interviews were not conducted right after their students’ participation in IRF; instead they were conducted between a few months to one year after (at the beginning of the 2016–2017 school year). This may have affected the results of the interviews because some teachers had a difficult time remembering the prior experience of their students. Nonetheless, many others conveyed great clarity and recollections because of the unique experience of the program.

This study included only six teacher interviews to comply with the NPS Office of Management and Budget (OMB) federal regulations. The OBM limits the number of people (including teachers) who can be asked the same questions to 10 people or fewer, unless they are park visitors (U.S. National Park Service, 2006). Also, the number of student journals utilized for the study (n=60) was low in size due to the lack of content in student journals. That is, only completed journals with writing and/or illustrations were selected for analysis. Several students from the Title I classes participating in the research had low reading and writing comprehension, therefore less ability to use their journals to write or draw their experiences.

Conclusions

Understanding the nature experience and learning outcomes of fourth-grade students is deemed important to evaluate the effectiveness of the EKIP initiative. More specifically, this helped begin the process of measuring the effectiveness of the Muir Woods Parks as Classrooms goal of providing an authentic park experience for underserved students of color from low-resourced communities. This study also added to the limited qualitative evidence, to-date, of the impact of the EKIP initiative.

Into the Redwood Forest

Teacher interviews indicated that park educators and practitioners need to consider ways to make the IRF classroom lessons more interactive for students to attain a greater connection with nature. Moreover, the results suggest the IRF program can further incorporate culturally relevant lessons in the inquiry-based curriculum that encourage students to connect with the natural environment of Muir Woods (Marx et al., 2004).

Future research about prior forest fears connected to students of color could also offer greater insight for NPS staff regarding how to design a relevant and more welcoming program. Evidence illustrates those with less direct experiences can be most frightened of nature (Bixler & Floyd, 1997), for a variety of reasons that differ across cultures (Warren et. al.,2014). According to Bixler and Floyd (1997), those with few direct nature experiences associate fears based on messages from parents, peers, negative media images, or ignorance. Their research suggests that outdoor youth programs should demonstrate the rewards of being in nature to help apprehensive youth make fitting perceptions of unpleasant fears. This present study could potentially assist underserved students of color in clarifying their fears, thus shaping greater connections with park environments.

Outdoor Education Programs for Underserved Youth

Connecting underserved youth of color to national parks is critical for the survival of public lands and waters because more than half of children in the nation are anticipated to be of different race and ethnicity by the year 2020 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015). As Outley and Witt (2006) affirmed, many racially diverse youth have historically been considered “underserved” in experiencing and learning about the natural environment. Subsequently, through this first adventure into a redwood forest, students in this present study were exposed to new concepts of nature and the cultural traditions of the first/indigenous people of Muir Woods through inquiry-based learning. For these youth, nature generated positive feelings of happiness, excitement, and wonder, which prompted them to lessen their fear of nature, and even to champion an emerging environmental stewardship ethic. Students communicated the experience also developed empathy for nature and led them to discover reasons to value and care for the environment. Youth from different racial and cultural backgrounds felt welcomed by discovering many aspects of comfort displayed by the NPS rangers along with the fact they could return to the park with their EKIP passes. However, to successfully provide students of color with programs that are more relevant to them, park professionals need to design programs that are modeled on the appropriate cultural framework and connect to students’ lived realities (Outley & Witt, 2006). IRF attempts to reflect a cultural framework and the Muir Woods park staff has already identified areas of improvement based on this study. This current investigation also demonstrates how and why other national parks might analyze their programs to integrate an interdisciplinary approach rooted in the culture of the park’s audience.

Every Kid In a Park. The goal of the EKIP program was to connect underserved youth of all backgrounds with the great outdoors (The White House, 2015). The National Park Foundation committed to providing transportation grants to schools in need to help remove barriers for underserved youth to access public lands and waters (National Park Foundation, 2017). However, transportation funds for one-time visits may not be enough for underserved students of color and their families to access parks in the future. The National Park Foundation (2017) established EKIP with a purpose of helping “engage and create our next generation of park visitors, supporters and advocates” (About Every Kid In a Park section, para. 2).

Underserved youth should have more than one opportunity to visit their national parks to create long-term meaningful relationships with these crown jewels and these spectacular environments. Thus, understanding how many students used their EKIP vouchers to return to Muir Woods or other national parks is an important way to track the value and success of the program. Although, EKIP passes were tracked at each national park site, they were not individually tracked by program, such as Parks as Classrooms programs. EKIP should be aware of these challenges and develop ways to actively mitigate these barriers with underserved and low-resourced communities.

Muir Woods offers profound experiences for the young eyes that look up at the majestic trees. The forest extends incredible opportunities for underserved youth to experience their senses, curiosity, joy, and empathy towards one of the last remaining old-growth forests proximal to an urban center (i.e., San Francisco Bay Area). Programs like EKIP empower youth, in general, to be present in natural places that are sometimes rarely entered by many underserved youth of color, specifically.

The EKIP initiative is another step towards reducing certain barriers that discourage youth of color and their family from visiting national parks and other wild areas; however, the National Park Service and other interested agencies must think critically of new ways to reduce or remove other constraints to participation. This, and other research (e.g., Aaron & Witt, 2011; Brody, 2001), suggests that authentic primary experiences lead youth to enjoy natural spaces, and therefore encourage appreciation of nature. Without formulating such positive attitudes, underserved youth are unlikely to develop the behaviors needed to conserve these areas (Outley & Witt, 2006; Paisley et al., 2014; Warren et al., 2014). And, such failure would limit the future of both this growing demographic across America and potentially predict a bleak future for citizens’ support of national parks and other wild spaces. The consequences could be devastating for all people.

References

Aaron, R.F., & Witt, P.A. (2011). Urban students’ definitions and perceptions of nature. Children, Youth and Environments, 21(2), 145–167.

Auwaerter, J. E., & Sears, J. F. (2006). Historic resource study for Muir Woods National Monument. Retrieved May 6, 2017 from https://www.nps.gov/muwo/learn/historyculture/upload/muwo-hsr2006.pdf

Bixler, R. D., & Floyd, M. F. (1997). Nature is scary, disgusting, and uncomfortable. Environment and behavior, 29(4), 443–467.

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40.

Brannen, J. (2005). Mixing methods: The entry of qualitative and quantitative approaches into the research process. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(3), 173–184.

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

Brody, M. (2005). Learning in nature. Environmental Education Research, 11(5), 603-621.

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area (2015). Education. Retrieved September 24, 2015 from http://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/education/index.htm

Golden Gate National Recreation Area (2016). Education. Retrieved May 13, 2016 from http://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/education/index.htm

Golden Gate National Recreation Area (2017). Ohlones and Coast Miwoks. Retrieved May 6, 2017 from https://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/historyculture/ohlones-and-coast-miwoks.htm

Jarvis, J. (2016, November 22). National parks turn into classrooms to turn a new generation into nature lovers. Retrieved March 07, 2018, from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/national-parks-turn-classrooms-turn-new-generation-nature-lovers#transcript

Kiernan, T. (2012, April). Connecting youth to our national parks. Huffpost. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/tom-kiernan/national-park-week_b_1441694.html

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Larson, L.R., Castleberry, S.B., & Green, G.T. (2010). Effects of an environmental education program on the environmental orientations of children from different gender, age, and ethnic groups. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 28(3), 95–113.

Louv, R. (2008). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. New York: Workman Publishing.

Marx, R. W., Blumenfeld, P. C., Krajcik, J. S., Fishman, B., Soloway, E., Geier, R., & Tal, R. T. (2004). Inquiry-based science in the middle grades: Assessment of learning in urban systemic reform. Journal of research in Science Teaching, 41(10), 1063–1080.

McGrady, V. (2015, February). President’s ‘Every Kid in the Park’ initiative offers free access to fourth graders and their families. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/ vanessamcgrady/2015/02/19/presidents-every-kid-in-a-park-initiative-offers-free-access- to-fourth-graders-and-their-families/#5f6a31e515fc

Monroe, M. C. (2010). Challenges for environmental education evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33(2), 194–196.

National Park Foundation (2017). Every kid in the park. Retrieved May 8, 2017 from https://www.nationalparks.org/our-work/campaigns-initiatives/every-kid-park

National Park Service (2015). Administration launches every kid in a park pass. Retrieved May 8, 2017 from https://www.nps.gov/resources/news.htm?newsID=69ECDF5E-0728-8C3F-A49B876FBCFB8C93

National Park Foundation. (2001). PARKS: Parks as Resources for Knowledge in Science: National Program Evaluation Final Report. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University Printing Facility.

Outley, C.W., & Witt, P.A. (2006). Working with diverse youth: Guidelines for achieving youth cultural competency in recreation services. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration, 24(4), 111–126.

Paisley, K., Jostad, J., Sibthorp, J., Pohja, M., Gookin, J., & Rajagopal-Durbin, A. (2014). Considering students’ experiences in diverse groups: Case studies from the National Outdoor Leadership School. Journal of Leisure Research, 46(3), 329–341.

Patchen, T., & Cox-Petersen, A. (2008). Constructing cultural relevance in science: A case study of two elementary teachers. Science Education, 92(6), 994–1014.

Rozenszayn, R., & Assaraf, O. B. (2011). When Collaborative Learning Meets Nature: Collaborative Learning as a Meaningful Learning Tool in the Ecology Inquiry Based Project. Research in Science Education, 41(1), 123–146. doi:10.1007/s11165-009-9149-6

Scott, G., Boyd, M., & Colquhoun, D. (2013). Changing spaces, changing relationships: The positive impact of learning out of doors. Australian Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 17(1), 47–53.

Tardona, D.R., Bozeman, B.A., & Pierson, K.L. (2014). A program encouraging healthy behavior, nature exploration, and recreation through history in an urban national park unit. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 32(2), 73–82.

The White House (2015). Administration launches every kid in a Park Pass. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/09/01/administration-launches-every-kid-park-pass

Thomson, G., Hoffman, J., & Staniforth, S. (2003). Measuring the success of environmental education programs. Ottawa: Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society and Sierra Club of Canada.

United States Census Bureau (2015). New census bureau report analyzes U.S. population projections. Retrieved March 15, 2017 from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2015/cb15-tps16.html

U.S. Department of Education (2015). Programs: Improving basic programs operated by local educational agencies (title I, part a). Retrieved May 17, 2017 from https://www2.ed.gov/programs/titleiparta/index.html?exp=0

U.S. National Park Service (2003). Field guide to national park labs. Washington, DC: National Park Foundation.

U.S. National Park Service (2006). Guidelines and submission form for expedited review of NPS sponsored public surveys, focus groups and field experiments. Washington, DC: National Park Service.

Warren, K., Roberts, N.S., Breunig, M., & Alvarez, M.G. (2014). Social justice in outdoor experiential education: A state of knowledge review. Journal of Experiential Education, 37(1), 89–103. doi:10.1177/105382591351889.

Wu, H.K., & Hsieh, C.E. (2006). Developing sixth graders’ inquiry skills to construct explanations in inquiry-based learning environments. International Journal of Science Education, 28(11), 1289–1313.