Journal of Interpretation Research

Volume 23, Number 2

A Comparison of Traditional and Facilitated Dialogue Programs in Grand Teton National Park

An Evaluation for the Future of Interpretive Programs

Pat Stephens Williams, Ph.D.

Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture

Stephen F. Austin State University

Nacogdoches, TX 75962-6109

stephensp@sfasu.edu

936-468-2196

Ray Darville, Ph.D.

Department of Anthropology, Geography, and Sociology

Stephen F. Austin State University

Nacogdoches, TX 75962-3047

rdarville@sfasu.edu

936-468-2256

Matthew McBroom, Ph.D.

Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture

Stephen F. Austin State University

Nacogdoches, TX 75962-6109

mcbroommatth@sfasu.edu

936-468-2469

Abstract

As part of finding their path for the next hundred years, the National Park Service is exploring diverse ways to engage the public and help create systemic changes in the way that the public interacts with each other. Facilitated dialogue in interpretive programs has been one of those ways. Traditionally, the public has embraced programming based on the expert and delivery, whereas the new direction leans toward an audience-centered, facilitated experience. To determine how this shift is affecting the experience related to interpretation in the parks, Grand Teton National Park (GRTE) conducted a study in 2015 and 2016. This multi-method study (this article presenting one slice) is based on the research model by Stern, et al (2012), which examined program and visitor characteristics among 56 live interpretive programs in Grand Teton National Park. Our goals were to compare traditional program with facilitated dialogue programs and to compare program characteristics over these two years. Findings indicate that traditional programs were significantly more attended than facilitated dialogue programs. However, when examining program characteristics, facilitated dialogue programs received significantly higher program evaluation scores than traditional programs. Adherence to the four-step Arc of Dialogue model was strongly and positively correlated with program characteristics.

Keywords

natural resource interpretation, facilitated dialogue, interpretive programs, Grand Teton National Park

Introduction

Historically, visitors have sought out and enjoyed interpretive programming that has often been essentially “sages on stages” as they have dispensed facts and figures in one-way directional communication about their respective parks. Anyone having visited Grand Canyon, Grand Teton, Yellowstone, or dozens of other national parks can envision the ranger dressed in uniform standing and providing what amounts to a lecture, or talk, to visitors. This essentially one-way communication has been used for decades and is a time-honored tradition. Many individuals visiting parks seek out these experiences and enjoy them greatly. However, as the National Park Service has celebrated its centennial on August 25, 2016, some park managers and interpreters are considering anew their approaches to non-personal and personal interpretation to more effectively reach park visitors. While they have maintained this interpretive approach historically, an innovative approach is beginning to receive attention—audience-centered using the facilitated dialogue approach. This approach is a two-way form of communication designed to encourage more active engagement of visitors in critical thinking and communication about park values, goals, and meanings. This approach is more of a “guide on the side” approach in which visitors are encouraged to talk with the ranger and with each other in a focused facilitated program. The National Park Service hopes this approach may reach beyond the boundaries of the parks to continue to facilitate stewardship, but also to increase the skills of society to work together for common positive goals.

This research study of interpretive programs in Grand Teton National Park had two broad goals: (1) to examine interpretive program characteristics of both facilitated and traditional programs and (2) to study attendee characteristics. The study’s focus was on evaluating selected programs offered during the summers of 2015 and 2016.

Our specific objectives for this study were to gather data on attendees at interpretive programs, examine program characteristics, and compare traditional programs with facilitated dialogue programs.

Literature Review

Natural and cultural interpretation in parks, especially national parks, has been ongoing for over 100 years. Stephen Mather, the first NPS director, may have led interpreters toward the “sage on the stage” approach when he commented that appreciation would come only through education. And, thus, it is one of the most important duties of any interpreter to provide facts and figures (education) to the American public (Shankland, 1970). Enos Mills (1920), one of the early interpreters used term “nature guiding” to describe his form of interpretation. Stephen Mather provided more acceptance to this emerging field when he discussed interpretation as a legitimate process to be used in a variety of settings to get visitors more knowledge of and sensitivity to a cultural or natural object. By the beginning of World War II, “interpretation” had replaced “nature guiding” as the chosen vernacular. When Tilden first wrote Interpreting Our Heritage in 1957, interpretation was accepted widely as an important activity to be conducted. While Tilden’s background was as a newspaper reporter and author, he turned his attention to understanding and analyzing resource interpretation in several United States national parks. Through his research, he defined interpretation as a profession and then he articulated effective methods of interpretation (what are called best practices today). These six principles continue to be taught in collegiate-level interpretation courses and continue to inform interpreters throughout the world.

Tardona and Tardona (1997) make a compelling argument, which acts as a partial foundation for facilitated dialogue. They argue that the United States is increasingly becoming more culturally and ethnically complex. Furthermore, culture and learning must be considered by any interpreter because people have diverse backgrounds and learn in different ways. The traditional interpreter, while effective with some individuals, simply is out-of-step with other visitors. These scholars call for interpreters to acknowledge that different visitors learn best or have better experiences when a teaching method best matches their learning style. A strength of facilitated dialogue is that it allows visitors with different backgrounds, values, perceptions, beliefs, and other cultural notions to express themselves openly in a safe place. Facilitated dialogue allows visitors to learn from each other, not simply an interpreter. In other words, facilitated dialogue allows for peer learning to take place and possibly a paradigm shift in understanding different perspectives by engaging with visitors different from themselves. Facilitated dialogue allows social diversity to be on display as individuals seek to understand natural places and their places in the world.

Facilitated Dialogue as an Interpretive Technique

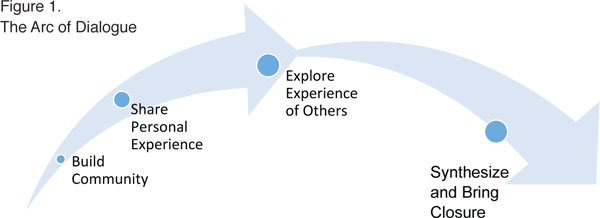

Recently, professionals have sought to create a more active, engaged interpretive experience for visitors to parks, museums, and other appropriate venues. Facilitated dialogue (National Park Service, 2014) is a “form of interpretive facilitation that uses a strategically designed set of questions—an “Arc of dialogue”—to guide participants into a structured, meaningful, audience-centered conversation about a challenging or controversial topic.” This interpretive technique (Figure 1) is designed to assist visitors to have a structured conversation centered on controversial topics such as climate change, race/ethnic relations, slavery, endangered species, and other such areas of interest. Interpreters employing this approach are encouraged to move the participants through four consecutive phases: (1) Building Community, (2) Sharing Personal Experiences,

(3) Exploring Beyond Our Own Experience, and (4) Synthesizing and Bringing Closure to the Dialogue (National Park Service).

In “Building Community,” the interpreter (facilitator) builds safety and acceptance and provides information regarding the topic and the purpose of the dialogue. During this phase, a facilitator should engage in a variety of techniques to “break the ice” and to have participants develop a sense of community and safety in this non-traditional type of program (National Park Service, 2014). Several of these techniques, or similar ones, may be found in other places, such as in rhetorical practices, conflict management and mediation. Sample questions might be to ask attendees where they are from, or to ask them to describe themselves in five words or less. At the end of this phase, attendees should feel welcomed and not threatened. They should feel accepted. They should be ready for more personal sharing when, in phase 2, they are asked to share a meaningful, personal experience.

In phase 2, sharing our experiences, a facilitator asks participants to think about their own experiences concerning the topic and to share those with one another. Questions to generate this form of sharing should be open-ended and welcoming so that everyone is perceived to be equal among group members. This sharing should be done non-judgmentally. Questions should allow, even encourage, members to share different experiences, not simply similar experiences. This phase allows attendees to begin to think about other’s experiences, which are different from their own.

Then, in phase 3, exploring experiences of others, a facilitator encourages participants to move beyond their own experiences so that they engage in inquiry and learn with and from one another (especially those whose experiences are different from their own).

Finally, in synthesizing and bringing closure to the dialogue (phase 4), a facilitator helps participants to connect ideas, perspectives, and information gained during the program. Ideally, the facilitator will use this model (or something similar) as he or she plans the program. And, it is critical that the facilitator makes it all the way through all four phases of the Arc so that there is a sense of closure to the program.

Interpretation Research

This slice of our multi-method research is based on a recently conducted national study model of live interpretive programs in the United States National Park Service (Stern, Powell, Martin, & McLean, 2012), sponsored by the National Park Conservation Association’s Center for Park Management. In 2011, a team of four researchers attended 376 live interpretive programs in 24 NPS cultural and natural resource units. Researchers conducted brief interviews with interpreters and collected data on 56 characteristics associated with the programs and their interpreters. Moreover, they conducted post-program surveys among the visitors, collecting data from some 3,603 program attendees. These researchers measured program outcomes, including level of satisfaction with the program, visitor experience and appreciation, and behavioral change among visitors. Their work was designed to see if they could identify best practices, which were associated with positive program outcomes. They identified 15 best practices, ranging from confidence to avoiding making uncertain assumptions about the audience. We based our research methodology on their methodology and overall research work.

Methods

The general methodology for this study was unobtrusive observation at selected interpretive programs in Grand Teton National Park during summer 2015 and summer 2016. Using direct observation with trained research assistants, data collection occurred in Grand Teton National Park. After each program, researchers completed a data collection form, which measured selected program characteristics as well as aggregate visitor characteristics, including the level of step completion in the Arc of Dialogue.

Study Site

Grand Teton National Park is in western Wyoming, south of Yellowstone and east of the Idaho state line. Long considered a flagship national park since its establishment in 1929, Grand Teton now welcomes almost three million visitors annually. The number of recreational visitors is clearly on the increase from a recent low of 1.2 million in 1988 (the year of the Yellowstone National Park fires) to a high of 3.2 million in 1977. It is annually one of the 10 most visited parks in the United States—eighth most visited in 2015 (http://www.npca.org/exploring-our-parks/visitation.html). In 2016, well over 3.1 million recreation visitors were recorded. The park has unparalleled scenery for those who simply want to take in the sights, but individuals visit the park for other recreational opportunities, including mountaineering, hiking, fishing, boating, skiing, and cycling. Besides the natural and cultural history of the park, it also has a commercial airport within its boundaries, which makes for easy access for visitors and dignitaries. For those wanting an interpretive experience, the park maintains visitor centers and ranger stations at Moose (Craig Thomas), Jenny Lake, and Colter Bay. The interpretive division at GRTE is known for its cutting-edge approaches to interpretation and is often used as a trial area for changes in visitor interaction techniques.

Programs Attended

During the period of July 18 through July 29, 2015 a total of 26 interpretive programs were attended in four districts of Grand Teton National Park: LSR Preserve, Moose, Jenny Lake, and Colter Bay. Of these 26 programs, some programs were advertised as facilitated dialogue, such as Lakeshore Conversations at Jenny Lake, while the rest were traditional interpretive programs. Based on anecdotal evidence, we believe some program participants knew what to expect in facilitated dialogue programs while some did not know what to expect; we are not certain, at this time, if there were significant differences in audience composition. In summer 2016, another 30 programs were selected for study, yielding a total of 56 studied programs. Selections, approved by park interpretation managers, were made based on attempting to balance the selected programs compared to the overall program offerings throughout the park, type of program, location of program, and logistics.

Data Collection

Two researchers attended each studied program. Researchers participated as attendees but did not dominate discussion or any other program activities. They remained as unobtrusive as possible and did participate in program activities. Upon completion of the program, the researchers completed the program demographics form and the program characteristics form. This data collection form was adapted from the Stern (2012) study, following their form closely. Thirty program characteristics were identified as being particularly important for study objectives. These all related to salient program characteristics and included such program aspects as introduction quality, transitions, verbal engagement, affective messaging, novelty, place messaging, and more than 20 others. Measurement conformed to nominal and ordinal level of measurement with some questions employing nominal measurement (such as use of props) with other questions employing ordinal measurement (such as physical engagement with four ordered attributes). Data concerning the Arc of Dialogue was discussed between the trained observers for comparison and consistency. In addition, we collected program-related data including attendee characteristics.

Data

Upon completion of data collection, researchers entered data in an Excel file. An SPSS data file was constructed using standard techniques and then data were transferred into IBM SPSS Statistics (Professional Version 24) for analysis. Once in SPSS, randomly selected data records were checked for accuracy and standard data checking techniques were employed to check for wild codes and coding errors. Finally, standard statistical procedures were conducted to answer research questions and test hypotheses.

Hypotheses

- Number of males, females, adults, children, Whites, Blacks, and Asians will vary significantly by type of program (traditional vs. facilitated).

- Program characteristics will differ significantly by type of program (traditional vs. facilitated).

- Total program scores will increase between 2015 and 2016 for both program types.

- There will be a positive relationship between total program score and score on Arc of Dialogue.

Results

Program Attendees

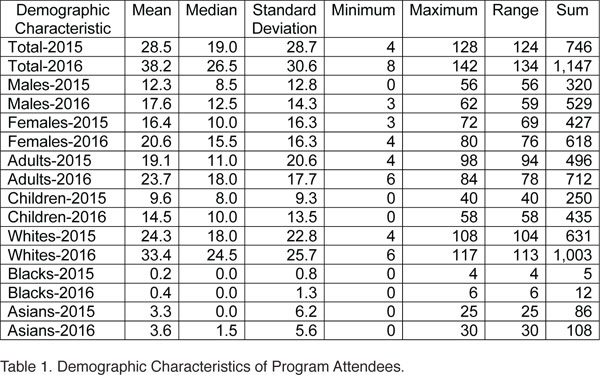

We counted the number of individuals, number of males, number of females, number of adults, number of children, number of Whites, number of Blacks, and number of Asians attending each program attended (Table 1). In 2015, the total number of attendees recorded at the programs was 747 with about 29 (M = 28.5) individuals attending each program. In 2016, we observed 1,147 attendees (M = 38.2). In both years, there were fewer males (M = 12.3 in 2015 and M = 17.6 in 2016) than females (M = 16.4 in 2015 and M = 20.6 in 2016). Adults made up about two-thirds of program attendees while children made up the other one-third. Whites made up about 89% of program attendees while Blacks and Asians made up the remaining 11%. While the number of attendees increased by 10 per program as a total and for each demographic category from 2015 to 2016, these increases were not statistically significant.

General Program Characteristics

Because one of the study objectives was to compare traditional and facilitated programs, both types were studied. Of the 56 studied programs, 71% (n = 40) were traditional compared to 29% (n = 16) for facilitated dialogue programs. These percentages are consistent with overall program offerings in the park during these two summer seasons.

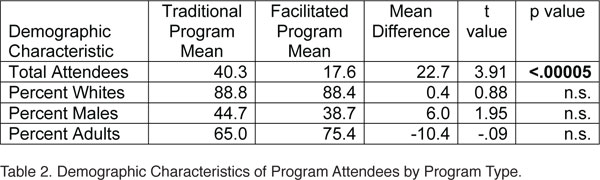

In hypothesis one (Table 2), we predicted demographic characteristics of program attendees (percent White, percent males, percent adults) would vary significantly by program type (traditional vs. facilitated). Race composition as measured by percent Whites vary very little (about 88% for both program types), and was not significant (t = 0.88, df = 54, p = .931). Gender composition as measured by the percent of attendees who were males varied between the two program types. About 44.7% of traditional program attendees were males while only 38.7% of facilitated dialogue programs were males; the percent difference was not statistically significant (t = 1.954, df = 54, p. = .056). In addition, the percent of the audience composed of adults did not significantly differ between the two program types (t = -0.957, df = 54, .351). Traditional programs were composed of about 65% adults while facilitated programs had about 75.4% adults.

Interpretive Program Characteristics

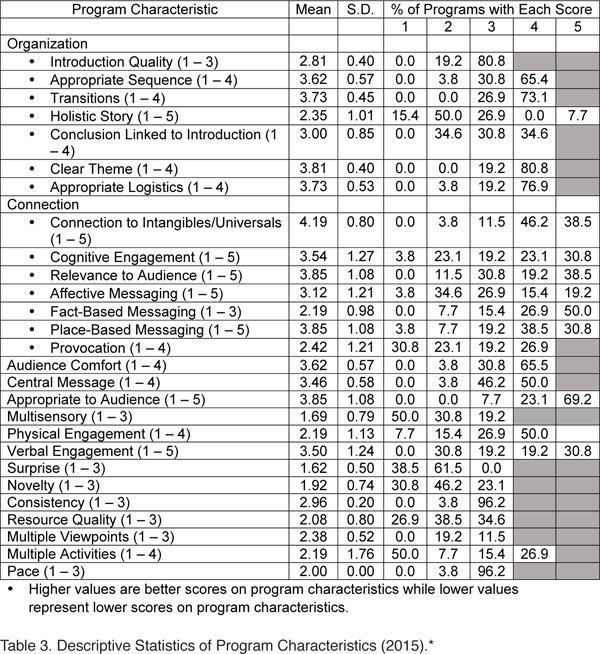

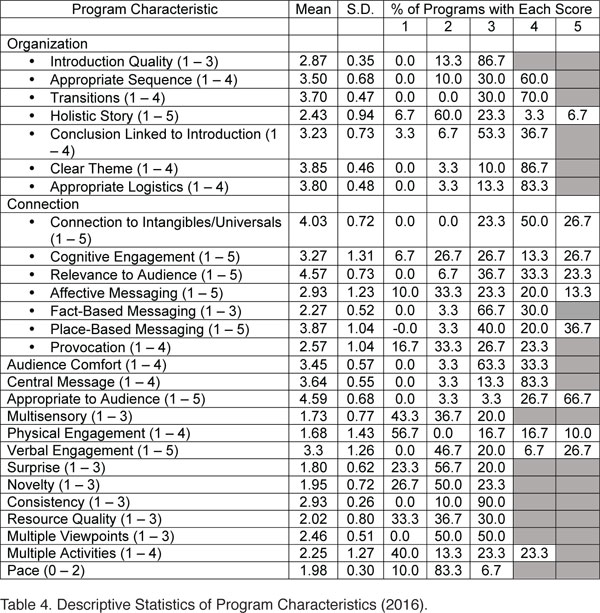

We measured 30 program characteristics for each program by the researchers based on the pre-developed coding system (Tables 3 and 4). Scoring was nominal and ordinal level following the methodology of Stern, et al. (2012). For each characteristic, the percent of programs with each score was calculated as well as the mean and standard deviation for each program characteristic. Relative to the maximum possible score, programs had the highest performance for pace, consistency, clear theme, introduction quality, traditions, and audience comfort. Programs had the lowest performance for multisensory, physical engagement, multiple activities, surprise, holistic story, and unexpected circumstance.

With hypothesis two, we predicted that mean program characteristics would vary significantly by program type (traditional vs. facilitated). Significant mean differences (Table 5) were detected for seven (25%) of the program characteristics: cognitive engagement (t = -5.62, p. < .001), relevance to audience (t = -2.75, p. = .011), affective messaging (t = -3.42, p. = .002), fact-based messaging (t = 3.20, p. = .008), provocation (t = -5.51, p. < .001), verbal engagement (t = -3.17, p. = .004), and multiple activities (t = -3.07, p. = .005). For all tests except fact-based messaging, facilitated dialogue programs had significantly higher means.

For organizational characteristics, no significant mean differences for the seven items were detected, and thus on these program characteristics, traditional and facilitated programs were much the same. However, for the connection dimension with its seven characteristics, five significant mean differences were found. Facilitated programs were rated significantly higher on cognitive engagement, relevance to audience, affective messaging, and provocation, while traditional programs were rated higher in fact-based messaging. Finally, facilitated programs were rated significantly higher in verbal engagement and multiple activities.

Total Program Characteristics

We assessed programs based on the coding form established by Stern, et al. A total program score was created by summing all item scores (Cronbach’s alpha = .91) for the programs for all program characteristics, yielding a possible low program score (assuming a program received the lowest possible score for each item) of 26 and a potential high score of 104 (assuming a program received the highest possible score for each item). We recognize that items do not have all of the same number of codes, or scores. However, because our study was a replication of the Stern study, we decided to follow their approach completely so that we could compare results across studies. Total program scores ranged from a low of 63 to a high of 102. There was a mean score of 79.2 (SD = 11.44) with a 95% confidence interval from 76.2 to 82.2. Facilitated dialogue programs (Table 5) had a significantly (t = -2.375, df = 24, p = .026) higher mean score (M = 84.8) compared to the traditional programs (M = 75.8). Significant mean differences were detected for seven program characteristics: relevance to audience, fact-based messaging, cognitive engagement, verbal engagement, affective messaging, provocation, and multiple activities. Facilitated dialogue programs had significantly higher means for six of the seven comparisons (relevance to audience, cognitive engagement, verbal engagement, affective messaging, provocation, and multiple activities), but for fact-based messaging, traditional programs had the higher mean (as should be expected).

Furthermore, we examined total program score by number of attendees. We did this was done to determine if program scores varied by size of audience keeping in mind the idea that interpreters could change their approach due to the size of their audience. The number of attendees was recoded into quartiles: 1-15, 16-25, 26-41, and 42-102. Mean program score was significantly and inversely related (r = -.564) to number of attendees (F = 9.16, df = 3 and 52, p = <.0005). The highest mean program score was associated with the smallest group size (M = 89.0) while the lowest program score was associated with the largest group size (M = 71.2). The two pairs of significantly different means were: (1) 1–15 and 26–41 and (2) 1–15 and 42–102.

Total program score was analyzed by gender of interpreter. Programs led by women scored 80.0, on average, while programs led by men averaged 77.5. The mean difference was not significant (t = 0.752, df = 54, p. = .455).

We hypothesized total program score would increase from 2015 to 2016 based on two factors: (1) we knew interpretive program staff was almost the same from year to year and with another year of experience, improvement should be seen, and (2) interpretive staff received additional training in interpretive techniques during May 2016 before the 2016 summer season. For traditional programs, total score increased slightly from 75.19 to 75.46, but the mean difference was not statistically significant (t = -0.090, df = 38, p. = .928. Among facilitated dialogue programs, mean program scores increased from 86.70 to 92.17; however, the mean difference of 5.5 points gain was not statistically significant (t = -0.944, df = 14, p. = .361).

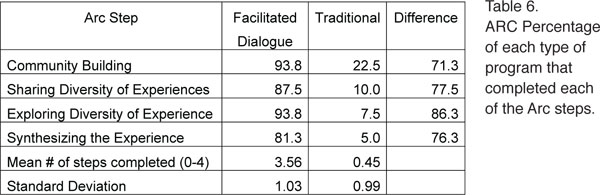

ARC Achievement

We counted the number of steps in the Arc of Dialogue that each program completed; the number could be as low as 0 (no steps) through 4 (all four steps). The results (Table 6) show that 12 of the 15 (77.5%) traditional programs did not reach even the first step of the Arc, but one traditional program did complete the entire Arc. Ten of the 11 facilitated dialogue programs reached at least step 3 of the 4, while one program did not reach any of the Arc steps.

Relationship between ARC Total and Program Characteristics

We hypothesized a positive relationship would exist between Arc total and program characteristics total score. The hypothesis was supported with a positive, very strong correlation (r = .69, p < .00005). The greater the Arc score for programs, the higher the program characteristics score. In addition, we performed an ANOVA test to see if Arc total was related to significant mean differences in total program scores. Significant mean differences were detected (F = 9.91, df = 3 and 22, p. < .00005). Programs having a total Arc score of 0 had a significantly lower mean (M = 73.8) compared to those achieving an Arc score of 4 (M = 91.1).

Conclusions and Recommendations

During summer 2015 and 2016, 56 traditional and facilitated dialogue interpretive programs conducted in Grand Teton National Park were studied using unobtrusive observation of park interpreters and their programs. Attending these programs were 1,147 individuals with number of attendees ranging from a low of four to a high of 128. Programs had a mean of 29 attendees with a median of 19. Attendees were more likely to be female (57%), adult (67%), and white (89%). Programs saw significant increases from 2015 to 2016 in all demographics measured: total, males, females, adults, children, Whites, Blacks, and Asians. Traditional programs had significantly more attendees than did facilitated programs for these demographics: total number of attendees, number of males, number of females, number of adults, number of children, number of Whites, and number of Asians.

We assessed programs based on the Stern, et al. (2012) coding form, assessing programs on 30 characteristics using nominal and ordinal classification schemes. There were some differences in program scores from 2015 to 2016, but the differences were not substantial. This could be taken in two ways. First, the stability across years could be considered a good outcome by managers. Effective, consistent programs should be a goal of interpretive managers. However, considering 2016 represented the second year of facilitated dialogue programs in the park, no or few performance increases might be viewed as demonstrating little growth among interpreters giving the programs.

Furthermore, we hypothesized that the two program types would be differentiated based on program characteristics. Facilitated dialogue programs had a significantly higher mean score on our 29 program characteristics compared to the traditional programs. For those interpreters and managers who value facilitated dialogue, this outcome is welcomed and helps to validate facilitated dialogue program effectiveness. Is facilitated dialogue appropriate for all interpreters? No. Is facilitated dialogue appropriate for all programs and/or content? No. Is facilitated dialogue appropriate for all audiences? No. However, facilitated dialogue programs out-performed traditional programs on total and on several individual program characteristics, including consistency, clear theme, introduction quality, traditions, appropriate logistics, appropriate sequence, and audience comfort. As expected, traditional programs performed well in fact-based messaging.

In terms of Arc adherence, designed facilitated dialogue programs averaged 3.4 of the four steps and generally were in line with facilitated dialogue expectations. There were significant mean differences between facilitated dialogue and traditional programs, suggesting that interpreters were approaching and delivering programs appropriately based on pre-determined program type. The Arc of Dialogue is not simply an important conceptual model for interpretation, but given our results, adherence to the Arc can produce meaningful program outcomes.

So what are some of the implications from this research beyond those already discussed? First, understand that the research presented here is just one part of the multi-method study conducted in the Tetons. An additional slice was the collection of email addresses from willing visitors attending programs and the subsequent completion of an online survey about their experiences (OMB approved). Data analysis is occurring now and results will follow in a not-too-future article. Another slice was using the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) for the returning interpreters to see if those who were conducting facilitated dialogue programs seemed to fall into certain type categories. Much to the chagrin of some of the interpreters, it appeared that this technique can be learned and implemented with success by all of the identified MBTI types (at least at this park). The lack of embracing the “new” technique by all was not lost on us at the initial meeting in 2015 when one long-seasoned interpreter crossed his arms and articulately expressed his disdain for changing the way he had been conducting programs for over 20 years. And in his defense, knowing his expertise and program content, visitors were and are attending his programs for the “sage on the stage” experience.

In addition, know that when we started this research project, there were no known studies looking specifically at the effects of using facilitated dialogue on visitors, rangers, or parks. Our goal was to not only try to gather data about the use of the technique and effects on visitor experience, but also in testing different methods of data collection to obtain meaningful information and results about the technique, visitor preferences, and the ultimate holy grail of measuring change in visitor perspective. One of the goals of using facilitated dialogue has been to reach beyond park boundaries and into the community—meaning the visitor goes through the experience of paradigm shift and learning the technique of exchanging perspectives to reach that shift and ultimately would apply those changes in their home base—learning about different perspectives, shifting behavior to more accepting of differences and similarities of the human species, etc. Since this research was conducted, two key details have occurred: 1) the NPS has been expanding its focus on facilitated dialogue to a more holistic approach of audience-centered interpretation with facilitated dialogue providing one key technique to meet that goal; and 2) we are hearing through the grapevine (mostly anecdotally) of additional efforts to conduct site specific research so results of those efforts may be forthcoming in the near future. We suspect, given the movement toward more audience-centered interpretation, that research efforts may lean more in that direction.

After two years of closely studying the use of facilitated dialogue, there are additional observations that may be of interest to trainers, managers, and other researchers. It is important to strongly state that at no point was this study meant to assess or judge the interpreters’ abilities or performances. It was also important that this was conveyed to the interpreters. Their willingness to share their efforts and growth were essential to helping us understand the full picture of using facilitated dialogue. In fact, at one point we discussed how conducting programs using the technique was actually changing the interpreter. Given that most of the interpreters were longtime seasonals returning to other jobs in home communities, we pondered how their own paradigm shifts were affecting their winter communities.

At GRTE interpreters had complete support by administrators to invest in building their craft with this technique and that investment showed in the delivery of the programs. The chief of interpretation had hosted a national training previously and continued to provide training support for the rangers. In addition, the superintendent at that time and current director of NPS, David Vela, stated they had permission to fail in the name of trying new ways to engage with the public and effect change. The result was we observed a deep level of engagement by the interpreters to hone their craft using this technique. The facilitated dialogue technique discussed here uses the Arc of Dialogue as its key concept model. Several of the interpreters expressed the challenge of overlaying the model on programs when taking into consideration some of the differences in attributes, such as content, length, site, and number of attendees. For instance, one interpreter talked about the difficulty of reaching all four components of the Arc in a 15-minute program. Another example was a two-hour lake hike with a high number of attendees. Though that would seem to be extremely challenging, the program was identified as one of the best examples of fully meeting the intent and concept of the technique. In the end, use of the technique seems to mirror what we already know about interpretation in general—that it is as much art as it is science and its success depends on a combination of many components. It was obvious that the interpreters were much more comfortable, no surprise, in their second year of design and delivery. It was also pointed out that many of them use some form of the Arc for their program in an effort to engage and include the audience in the experience of the program and the park.

The programs developed and identified to be facilitated dialogue remained the same over the two years of the study. Each of the four regions of the park had at least one facilitated dialogue program. The titles and descriptions of the programs were listed in the park newspaper schedule. In a discussion with the research team, some suggested that the titling may need to be a bit more “exciting” and that the descriptions may need to be more clear on what the visitor might expect and written in a more compelling way. Of course, this also goes back to the discussion of what experience the visitors are searching for in attending programs. Are they looking for enlightenment through discussion, escaping the deep thinking of day-to-day life, learning about the park’s natural and cultural uniqueness? The facilitated dialogue approach increases the variety of interpretive experiences available for the visitor and their families and adds one more tool for interpreters to use in helping those visitors connect with the resource.

Finally, we still have a long way to go in understanding how all of this may work in helping the NPS sort out its identity and role in the next century of its existence. Here, we have just begun to chip away at how facilitated dialogue fits into the mix of current and future interpretation. Both traditional and facilitated dialogue programs have strengths and both can be effective in national parks. Park interpretation managers and interpreters carefully consider a host of factors when designing and presenting interpretive programs and should continue to do so. Some key factors are revealed in this study. Given cultural, social, and demographic changes to the American society and national park visitors, effective natural and cultural resource interpretation is more important and necessary than ever.

References

Alderson, W.T. & S.P. Low. (1985). Interpretation of Historic Sites (2nd edition). Nashville, TN: American Association for State and Local History.

Beck, L. & T. Cable. (1988). Interpretation for the 21st Century: Fifteen Guiding Principles for Interpreting Nature and Culture. Sagamore Publishing.

Knudson, D. M., T. T. Cable, & L. Beck. (1995). Interpretation of Cultural and Natural Resources. State College, PA: Venture Publishing, Inc.

Mills, E. A. (1920). The Adventures of a Nature Guide. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page and Co.

National Park Service. Interpretive Facilitator’s Toolkit. Retrieved from http://idp.eppley.org/Interp-Toolkit.

National Park Service. (2014a). The Arc of Dialogue. Retrieved from

https://www.interpnet.com/NAI/nai/_events/Workshop_2014/Handouts.aspx

National Park Service. (2014b). What is Facilitated Dialogue. Retrieved from

https://www.interpnet.com/NAI/nai/_events/Workshop_2014/Handouts.aspx

Shankland, R. (1970). Steve Mather of the National Parks. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Stern, M J., R. Powell, E. Martin, & K. McLean. (2012). Identifying Best Practices for Live Interpretive Programs in the United States Park Service. Research Report for the U.S. National Park Service.

Tardona, J.H., & D. R. Tardona. (1997). Natural Resource Interpretation and Conversation Education in a Global Society. The George Wright FORUM. Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 44–50.

Tilden, F. (1957). Interpreting Our Heritage: Principles and Practices for Visitor Services in Parks, Museums, and Historic Places. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Tilden, F. (1967). Interpreting Our Heritage: Principles and Practices for Visitor Services in Parks, Museums, and Historic Places. (revised edition). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.