More than Just a Crash of Rhinos

A Self-Study of My Time as a Wildlife Interpreter

Alexandra M. Burris

Toledo Zoo & Aquarium and Indiana University

P.O. Box 140130

Toledo, OH 43614

Alexandra.Burris@Toledozoo.org

419-385-5721 x2049

Abstract

This study seeks to fill a gap in research on interpretation by using my experience as an interpretive guide to critically examine the goals of interpretation and the use of the best practices of interpretation. In particular, this study examines conflicts that arose between my own goals, the goals of the visitor, and the goals of the institution. I utilized self-study methodology including conversations with critical friends, journal entries, visitor evaluations, a literature review, and a review of video data of my own tours. Qualitative analysis of the data triangulated evidence from these sources to find emergent themes. The paper also discusses the growth that occurred in my own teaching as I struggled with utilizing the best practices of interpretation. I investigated two main areas—the goals of interpretation and the types of practices used to achieve these goals. Themes that arose included tensions with the establishment I worked for, tensions with the perceived goals of visitors, as well as struggles with the use of humor, personal connections, and silence. Findings from the study suggest a need for greater communication about goals and practices within informal and free-choice learning institutions. Implications for using self-study as a tool for improving interpretation are discussed.

Keywords

self-study, interpretation, free-choice education, wildlife education

All over the country free-choice and informal learning institutions have interpreters interacting with visitors on the front lines as teachers, entertainers, and ambassadors for their organization. These establishments, which include diverse venues such as zoos, museums, and aquariums, often have their own ideas on what makes a “great” interpreter. Perhaps it is someone able to effectively entertain the visitor, someone who successfully teaches the key concepts of their mission statement, or someone who inspires visitors to take action (Beck & Cable, 2011). Others assert that there are also certain factors specific to individuals that make them great at their job such as confidence, content knowledge, or public speaking ability (Stern & Powell, 2013). Particularly for free-choice institutions, which are distinct from formal and informal learning establishments in that the visitor chooses whether or not to come (and how spend their money), it is important to utilize best practices of interpretation that not only serve the mission but also serve the needs of the visitor.

To date, these sorts of claims regarding the best practices of interpretation have often been asserted from an “outside” perspective by utilizing visitor questionnaires and experimental treatment groups to determine the desired qualities among interpreters. While useful, these studies fail to account for the real, lived experiences of interpreters. Ethnographic and qualitative research is lacking in the field of interpretation, particularly those using self-study methodology. Self-study benefits the field by providing a look inside the actual practice of interpretation and providing useful data for improving our teaching methods and training employees at free-choice and informal education centers. Self-study requires rigorous analysis of one’s own practice that involves actively challenging deeply held assumptions. I argue that although self-study is not often used within the field of interpretation, this method will not only help researchers learn more about the act of interpretation but aid in creating more reflective practitioners that seek to improve their craft.

This study seeks to fill this gap in the literature by focusing on my time as an interpretive guide at a free-choice wildlife education center. My job at this institution was to provide interpretive tours aboard a “safari” type excursion while providing interpretation of the animal species and conservation topics. The self-study consisted of conversations with critical friends, journal entries, visitor evaluations, a literature review, and a review of video data of my own tours. In particular, this study examines the conflict between my own goals as a doctoral student in science education, the goals of the visitor, and the goals of the institution I was working for. The paper also explores many of the struggles I had in utilizing the best practices of interpretation and the growth that occurred in my own teaching as a result of this study. I end with implications for organizations and individuals that practice interpretation and discuss how self-study can be used as a method for practitioners to analyze and critique their work as interpreters and educators.

Review of Relevant Literature

I begin this self-study with a brief review of literature on interpretation meant to shed light on some of the most common purposes of interpretation as well as the best practices of interpretation as supported by theory and empirical evidence. The review consists both of empirical studies and professional development literature that provide a wide base of support for some key pedagogical and personal attributes of quality interpreters. The background is provided here to illustrate the qualities of interpretation that I used as a reference in this study to compare my own practice to widely held “best practices” and is organized to set up my two main research focuses: the goals/purpose of interpretation and the best practices of interpretation.

Purpose of Interpretation

No review of interpretation would be complete without mentioning Freeman Tilden. Tilden defines interpretation as: “the work of revealing, to such visitors as desire the service, something of the beauty and wonder, the inspiration and spiritual meaning that lie behind what the visitor can with his senses perceive” (Tilden, 1957). Modern definitions have not changed much with Beck and Cable (2011) defining interpretation as “an informational and inspirational process meant to elicit a response from the audience including wonder, inspiration, and action.”

Specific to wildlife education facilities such as zoos, aquariums, and national parks, the goals of interpretation for these organizations often align with the broader goals of the field of environmental education. The most basic definition of environmental education was proposed by the Tbilisi Declaration (UNESCO-UNEP, 1978) which states that the purpose of environmental education is to develop among citizens a combination of content knowledge as well as the skills, attitudes, and motivation needed to take responsible environmental action. Similarly, Falk, and Heimlich (2009) assert that behavior change should be the major goal and outcome of free-choice environmental education. In particular, most wildlife education centers have conservation, protection, or preservation of species as their primary mission (Merriman & Brochu, 2009). We know from the business world that mission statements are extremely important in focusing the activities of an organization (Pearce & David, 1987). As an interpreter, an understanding of one’s mission is important because most wildlife facilities now include education about conservation as a key means of achieving this mission (Falk et al., 2007).

Best Practices of Interpretation

Many books and articles have been written on the best practices of interpretation. These often take the form of lists of strategies for improving the learning of visitors. Tilden’s (1957) six principles are still the most widely cited and used of such lists. Tilden’s principles illustrate the importance of relating to the visitor and creating a cohesive story. His use of words such as “revelation” and “provocation” define interpretation as an art form rather than simply a transmission of information.

In a more modern theoretical piece, Larry Beck and Ted Cable (2011) listed 15 principles of interpretation, but upon close examination, their list does not stray far from Tilden’s original six. Common elements of these works include relating to the participant, utilizing passion and inspiration in speaking, developing a cohesive theme, and using different techniques for different audiences. Once again we see words such as “intentional,” “thoughtful,” and “inspire.” The National Association for Interpretation (2009) emphasizes that interpreters need to use passion and enthusiasm to facilitate a connection between the interests of visitor and meanings of the resource (National Association for Interpretation, 2009). Additionally, studies from broader fields of education and psychology suggest internal states such as intrinsic motivation for tasks and self-confidence are equally if not more important for successful interpretation than these extrinsic behaviors (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Empirical Studies. While these lists are handy, perhaps more convincing are studies that back up these principles with empirical research. One such quantitative study by Stern and Powell (2013) sought to determine the characteristics of interpreters most associated with positive visitor outcomes by utilizing ranking to examine correlations between interpreter/program characteristics and three outcomes: visitor satisfaction, visitor experience/appreciation, and intention to change behavior. In general, the visitor outcomes were affected as much by the characteristics of the interpreter as the use of the aforementioned “best practices” of interpretation. Interpreter and program characteristics that correlated with positive visitor outcomes included: the confidence of the interpreter, authentic emotion and charisma, appropriateness for the audience, thematic organization, personal connections with guests, humor quality, consistency, a clear message, responsiveness, and multisensory engagement. Those that detracted from visitor outcomes included making false assumptions about the audience and an overly formal tone (Stern & Powell, 2013).

Interestingly, interpreters who expressed that a primary goal of their program was to increase the knowledge of the audience about their program’s topic had lower visitor experience/appreciation scores than those aiming to change their audience’s attitudes, appreciation, understanding, or desire to learn. Additionally, programs where the interpreter explicitly targeted behavior change as an intended outcome were more successful at doing so. This aligns with behavioral theory that interpretation shouldn’t be expected to change behavior unless that behavior is explicitly targeted (Stern & Powell, 2013).

A similar study by Stern et al. (2013) correlated more subjective and qualitative assessments of quality of guides with the same visitor outcomes discussed in the previous study. Some of the qualitative traits that seemed to most influence the visitor outcomes included the comfort of the interpreter (using a conversational tone), their apparent knowledge, eloquence, passion, charisma, humor, responsiveness, introduction quality, appropriate sequence, transitions, telling a holistic story, having a clear theme, and linking the introduction to the conclusion. These qualitative findings were very similar to the quantitative findings above but also provided specific examples of each of the qualities and best practices. For instance, the authors found that the most effective type of humor was the interpreter’s ability to poke fun at things rather than just using corny jokes (Stern et al., 2013).

Other similar studies that correlate best practices and visitor outcomes (both enjoyment and behavior change) in a quantitative manner reiterate these same themes. Skibins, Powell, and Stern (2012) found that best practices with the most influence on guests were: actively engaging the audience, tailoring to the audience, affective persuasive messaging, and demonstrating how to take action. Visscher, Snider, and Stoep (2009) found that interpretive scripts that included stories resulted in higher visitor outcomes compared to interpretive scripts that were only facts-based. Knapp and Benton (2004) undertook multiple case studies of interpretive programs in national parks and found that programs that related to the visitor and used innovative teaching techniques were most successful. Means of relating to the visitor included reading the audience and connecting to their prior knowledge while innovative techniques include avoiding didactic techniques, promoting interaction, and encouraging critical thinking via more constructivist teaching techniques (Knapp & Benton, 2004). Finally, Grenier (2011) examined docents considered to be experts and looked at the characteristics that set them apart. These included: extensive subject matter knowledge, utilizing prior experiences, adaptability, enthusiasm and commitment, and a sense of humor. The best docents integrated their past experience to learn how to do their job better and adapt to change (Grenier, 2011).

All of these studies point to many similar characteristics of effective interpreters. In particular, connecting to the audience, confidence of the interpreter, and clear organization emerged as front-runners. But it should be mentioned that visitors often have a bias toward ranking their satisfaction for interpretation as very high perhaps because of sympathy toward the interpreter and the differences in these studies represent more of a “good” to “better” scale rather than good versus bad (Stern & Powell, 2013).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to critically examine my own role as an interpreter in order to uncover realistic realizations of the “best practices” of interpretation from an insider’s perspective. It is hoped that by empirically exploring my own experiences, the findings will be applicable to other interpreters looking to improve their practice. The study was guided by two broad research questions:

1) What sorts of goals and motivations guide the work of interpreters when assessed from an inside perspective? How do these goals relate to the goals of institutions, visitors, and the field of wildlife education?

2) Which interpretive practices and skills emerge as the most successful in achieving these goals and how do they relate to literature regarding the best practices of interpretation?

Methods

A self-study methodology was selected in order to provide a much-needed “insider” view of interpretation. While many of the studies included in the literature review above contained qualitative components, these were the exception rather than the rule. Most research and evaluation in interpretation still focuses on surveys of visitor outcomes and pre-post tests (Hunter, 2012). Self-study fits well within the field of free-choice education research and its shift to constructivist paradigms. Modern researchers largely agree that visitors to free-choice institutions create meaning within their own personal, social, and physical contexts (Falk & Dierking, 2013). In a similar manner, self-study methodology can help practitioners explore their own conceptions of interpretation as it relates to the context of their work and motivations. Additionally, the rich description of the internal states of the researcher allows readers to better understand the ways that free-choice educators construct their own meaning of their work.

Specifically, self-study may fill in some gaps in the literature regarding interpretation by providing a systematic look at interpretation from an insider’s perspective. Self-study is defined by Dinkelman (2003) as an intentional and systematic inquiry into one’s own practice. The insider’s perspective provides the researcher with a unique perspective of special sensitivity and a shared understanding of the subject matter. Although the insider’s perspective is susceptible to bias, this may be countered by the access to information that an outsider would not have and the shift away from the dominant researcher-subject relationship present in more traditional ethnographic studies (Rabe, 2003). Key features of self-study as defined by LaBoskey (2004) are that it is self-initiated, improvement-aimed, and interactive. Self-study is more than simply reflecting on ones practice because it requires response with action and includes actively challenging one’s assumptions (LaBoskey, 2004). It is also argued that self-study advances knowledge about the field because those actually engaged in a profession are in the best position to study and improve upon the practice of that profession (LaBoskey, 2004; Rabe, 2003). The reflective aspects of self-study are particularly important for practitioners to be able to apply a critical look at their craft with the eye of a researcher trying to discover what works and what does not work in practice. The goals of self-study are to answer questions that are applicable to the broader field of education and offer fresh perspectives on established truths (Bollough & Pinneger, 2001).

While sharing some commonalities with research methods such as ethnography and auto ethnography, self-study is unique in that the former methods seek to form a rich, thick description of the subject in order to understand experience (Hamilton, Smith, & Worthington, 2008). The purpose of this self-study, rather, is to treat the self as a research subject by looking for patterns and commonalities that may be applied to practice. The researcher seeks to identify discrepancies between intention and action and get to the bottom of the cause of these discrepancies (LaBoskey, 2004). As such, the self-study incorporates interactions with others as a means of challenging one’s own thinking. These interactions with others increase the trustworthiness of the data by helping to address the bias that may be present in analyzing one’s own practice.

Context

This study took place over 11 weeks at a wildlife education center during which I was employed as an interpretive guide at the park. The center is a large conservation park in a rural area that houses animals in large open habitats. The animals housed at the center include rare and endangered species which are being conserved through captive breeding programs and research. In addition to their work with animals, the center also works with restoring and maintaining ecological function to their landscape. My job at the park was to drive passengers through the park while providing an interpretive tour to the general public. Up to 32 people may take the tour at a time and my task was to provide guests with information about the animal species and about conservation in general during the two-and-a-half-hour tour. Guides at the facility are provided training by shadowing experienced interpreters and provided with a packet of information about the main topics that should be covered, but the tour itself is largely created by the individual interpreter and may vary greatly among the staff. As a conservation park, there is an expectation among guests to receive some educational components on their tour, but the majority of guests attending the facility were families with children wishing to experience a “fun” day out.

It should be noted that I had worked at this facility for four summers prior to conducting this study. Over these four years I gained an understanding of the vocabulary and common practices utilized in the field of interpretation that put me in a unique position to delve into deeper questions regarding my own practice. However, this does point to a limitation of the study that it does not examine many of the common concerns of beginning interpreters such as fears of public speaking or the initial development of narrative. Instead, as a result of my experience, my concern was with reconciling the goals of interpretation with my actual practice.

Data collection and Sources

The primary data sources for this study were a written personal journal, visitor surveys, video recordings of my tour, and multiple critical friend meetings. In line with the broader theory of self-study, the use of multiple data sources work to triangulate the evidence for finding patterns in goals and practices. For example, rather than focusing on strict quantitative analysis of the survey, the results of the survey were used as a tool to qualitatively compare my perception of my practice with what was actually taking place and the visitors’ perceptions. Meetings with critical friends provided points of reflection that helped to address underlying bias and push my understandings of the patterns that were emerging from the other data sources. Each of these data sources is discussed in more detail below.

Journal. Throughout the course of the study, I kept a personal journal after each day of touring. The journal included my own thoughts and reactions to the tours I gave, my interactions with guests, and other situations I encountered that seemed relevant. In each entry I reflected on things I did well as well as areas for improvement.

Survey. In order to examine the outcomes of my tour and how my visitors perceived my tours, I created a survey that assessed visitor’s satisfaction with the tour and included open space to elaborate on what they learned from the tour. I included many questions related to how well they believed I achieved certain “best practices” (such as relating to their daily lives, content knowledge, passion) in order to compare my own thoughts about the tours to what guests were perceiving of me. I also asked visitors to rank how important many of these best practices were to them (for example, how important was humor to them on the tour). All of these rankings were Likert scales from 1 to 4 (not at all important to very important) with the exception of satisfaction from 1 to 10 (not at all satisfied to very satisfied). Sixty-nine surveys were collected from visitors at the end of 13 tours over the duration of the study. These surveys helped to triangulate findings from my journal and recordings by comparing my own perceptions with those of the visitor.

Video Recordings. At three points during the summer, I video-recorded my tours. I did this by asking three children between the ages of six and 12, two females and one male, to wear a GoPro camera strapped to their chest. This technique was chosen due to quality of recording (good audio and visual are gained from GoPro cameras) and the ability to capture some subset of guests’ real-time responses to my tours (Burris, 2017). The age range was chosen based on prior experience that families are more amenable to their children wearing cameras rather than the adult (Burris, 2017). The use of first-person recordings also connects well with the self-study methodology by providing the insider perspective of the visitor and their meaning making during the tour. The videos were used to create a transcription by hand of my “typical” tour as well as examine the real-time responses of a few visitors.

Critical Friend Meetings. Critical friends are a technique gaining prominence in the field of education for use in action research and professional development (Costa & Kallick, 1993). This method helps to provoke the researcher to look at the data through another lens and is important to the self-study methodology to help the researcher address their own biases. The purpose of critical friends is to clarify ideas and push the researcher to examine their thoughts from new perspectives. The first critical friend was a fellow graduate student, Kelly (pseudonyms are used in all cases) also studying science education at my university. I chose this critical friend because I believed she would have knowledge of the pedagogy we are being taught in graduate school but also because she had prior experience teaching in informal settings. Our meeting consisted talking through some of the stumbling blocks and issues I had been finding in my first month returning to touring as well as my struggle with defining the goal of my tours. The second “critical friend” meeting was with two coworkers, Leslie and Rachel. In this meeting I sought to learn more about what methods my coworkers used to work through some of the issues I had been having and if they had any suggestions. The conservation also enlightened me to other issues that my coworkers were facing that I may not have thought of.

Data Analysis

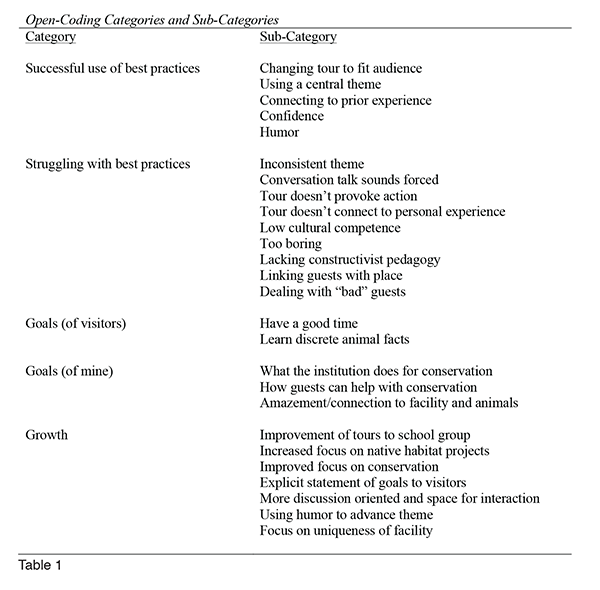

Open coding was used to break down my journal entries and critical friend conversations to look for patterns in the thoughts/ideas articulated. As I counted and tallied my references to certain topics or ideas, these were compiled into sub-categories which were then grouped together as themes and examined for alignment with the two broad research goals. Because the codes were created and combined in a movement toward creating hypotheses regarding my own thoughts, the method most resembled constant comparison (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The categories and subcategories are illustrated in Table 1.

Videos and tour transcripts were also coded in a grounded theory technique (Merriam, 2009) and analyzed in alignment with these broad categories: successful uses of best practices (fielding questions appropriately, using humor, theme development) and struggles with best practices (poor pacing/transitions, filler words, and portions that were too didactic). Any interactions that guests had with the tour were noted. The most frequent types of interactions among guests were: connecting the material to prior experience, exhibiting curiosity about an animal, answering a question I posed, restating something I said in different words, directly asking me a question, and affective statements of “liking” a certain animal. This process of open coding was emergent and new categories were created as new themes emerged (Glaser & Strause, 1967).

Trustworthiness

This study falls within a qualitative and constructivist framework and thus follows standards for credibility as discussed by Lincoln & Guba (1985). The internal validity of the research is inherent in the level of critical self-reflection and descriptions of my own world views and orientations. However, external sources of data were also included in the study to improve its reliability such as member checks with my critical friends and external review of the themes by my advisors (Merriam, 2009).

Findings

Throughout the study, a few main themes emerged. In accordance with self-study methodology, the most interesting themes were the ones that challenged my thinking regarding interpretation (LaBoskey, 2004). In particular I discuss the conflicts posed by my two overarching questions—what goals guide the work of interpreters? And what types of interpretive practices should be used to reach these goals? Each theme is supported with data from journal entries, critical friend meetings, video recordings, and visitor surveys. The nature of this data is focused on my own lived experience of what was happening in the moment. I conclude with a discussion on how I used my reflections on these themes and conflicts to improve my practice over the duration of the study.

Goals of Interpretation

In answering the first research question regarding the goals and motivations for interpretation, a few main themes arose: the conflict between my own goals and the goals of the institution, the tension between my goals and my perceived desires of visitors, and my own difficulties in executing these various goals during my tours.

Tension with the Establishment. The goals and purposes of my tours were a common point of reflection in my journals. Many times this manifested with my own frustration that my personal goals felt different from the ones proposed by the institution and the motivations I perceived that my visitors had for visiting.

My first frustration came upon hearing of a new mission of the institution. The old mission stated that the main goal of the institution was conservation while the new mission statement did not contain the word conservation and instead emphasized connecting guests with wildlife. Throughout the season I expressed my frustration that conservation was no longer a key component of the mission statement.

Connecting people with animals is great … but conservation should be the number one goal of our facility! But now that word isn’t even in the mission at all. (Journal Entry, 5/9/2016)

This came up in my discussions with my critical friends as well. In both informal and formal discussions with coworkers, all of us agreed that despite the change in wording of the mission, conservation was still the central focus on our tours. In fact, critical friend Rachel even indicated that she still recited the old mission as part of her tour.

This tension with the institution extended into my views on the training we received as interpretive guides. Multiple times in the summer I discussed with coworkers and friends that I believed that as guides we were trained to provide our guests with plentiful information about the animals, but information about conservation and conservation education were lacking. In particular, I asserted that the institution could benefit from an evaluation program—something that had not been done for the general public tour.

Me: I believe the general public tour should be equally valuable if not more so than the education we offer at our camps. People should come away from our tours passionate about [the institution] and if we do our jobs right in that way, they will want to spend the money to help conservation like management wants them to. (Critical Friend Communication, 7/19/2016)

Upon further reflections I found that some of my frustrations and tensions with the goals of the institution may have stemmed from differences in ideology from my courses and experiences in my Ph.D. program. In particular, I had just taken a course on environmental education (EE) and resonated with the principles of behavioral change that are an integral to quality EE.

Me: I talk about what we do … but I don’t really show them how they can help.

Kelly: Well, maybe making them aware of what [the institution] does can help them feel more connected. Awareness is step one.

Me: I feel like that’s just what zoos say to make themselves feel better

Kelly: Even just learning a fact about an animal may inspire them to learn more about the animal then they might share something about it on Facebook and this just begins a trajectory where they feel connected to want to protect the animal.

Me: I guess that’s true. But I feel like what we learned in class is that people don’t naturally just do stuff with awareness only … you have to teach them how. (Critical Friend Meeting, 6/12/2016)

This conversation points to my frustration with the underlying goals of zoos to only increase awareness about animals. Instead, I felt that it was my (and the institution’s) duty to provide visitors with concrete tools for taking action on behalf of conservation.

Building connections with animals while entertaining them may ultimately build appreciation … but is that a just cop-out because it’s easier to do than changing people’s actions? It’s a tough question because I guess in some ways the reason I am where I am today is because I went to zoos and developed a love of animals which started me on this path. (Journal Entry, 6/13/2016)

Despite the mission of the institution and my own admission that fostering an appreciation for animals is important, I was not completely satisfied with simply connecting people with wildlife. I felt that my underlying goals aligned better with those of environmental education—to provide visitors with the knowledge, motivation, and skills for taking responsible environmental action (UNESCO-UNEP, 1978). To me it was unclear if the institution’s mission aligned with these goals or if they believed that our job was primarily providing visitors with opportunities to connect to our animals via informative tours. This sort of discussion was not initiated by management throughout my time working at this institution, but in the future I believe these sorts of conversations about goals and purpose would benefit both interpreters and management at zoos and other wildlife education facilities.

Tension with Visitors. Throughout this study, it was my perception that visitors were primarily concerned with having a good time and learning facts about animals, and this perception created a tension with my goals for conservation education. Based on the cost of the tour and the high proportion of families with children, it isn’t unwarranted that guests would feel entitled to having an enjoyable experience. So the question becomes how to reconcile the visitor’s need for entertainment with the mission of the institution for conservation without decreasing the value of the experience.

One thing that is predictable is that most people just want to learn about quirky facts. I really don’t know how to, 1. get through to them the more general stuff like conservation and adaptations, and, 2. get them to realize that counts as learning. (Journal Entry, 5/25/16)

In some respects my perception was supported with the data from the surveys. When I asked visitors to rank certain statements for how important they felt they were in a tour, “facts about animals” had the highest average ranking for importance to visitors while the average for “what I can do for conservation” was considerably lower and often ranked as not important.

These views were further complicated by my own misconceptions that talking about conservation was inherently at conflict with my guests “having a good time.”

I guess really my purpose has always just been for my guests to have a good time and feel like they learned something. Ultimately I don’t have any misgivings that my tour is actually going to lead them to change their behavior. Which may be why people don’t report they are going to change their behavior on the surveys. If I don’t believe I can get them to change, why would they believe it? But is it my place to even try? For one, everyone hates when they feel like they are being preached at. And if they feel uncomfortable that takes away from their enjoyment of the experience and probably any learning they would come out with…. Is it so wrong I just want my guests to have a good time? Maybe it’s enough for them to leave with a positive view of [the institution] and our mission. (Journal Entry, 6/8/2016)

At that time I believed my goals for behavior change and conservation education conflicted with my ambition for my guests to leave the institution feeling like they had a good time. As a free-choice institution dependent on revenue from admissions, the importance of visitor satisfaction should not be ignored. But I found that my early conceptions about conservation education being incompatible with entertainment were flawed. As the summer progressed, I began to use different techniques to mediate my discomfort in conservation talk being “too preachy.” These will be discussed in the next section.

Best Practices of Interpretation

Right off the bat, I felt that the best practices of interpretation resonated well with my goals and the implementation my tours. After four years of guiding, I had a high level of confidence in my tours. I felt that I connected well with my guests and that most of my guests left having had a good time. In surveys distributed after my tours, every guest ranked their satisfaction as an 8 or higher with the average a 9.8 on a scale of 1 to 10. The most commonly used word to describe their tour guide (me) in the comments section of the survey was “knowledgeable” followed by “entertaining,” “friendly,” and “confident.” One typical response: “She was great, fun, and descriptive. [She] is awesome!” (Survey response, 6/4/2016)

If my primary goal was visitor satisfaction, then for the most part I was achieving it. However, I still wasn’t completely satisfied with the tours I was putting out. Most of my unease stemmed from my underlying goals as discussed in the previous section. Was I really doing all I could do to get my visitors to connect with the theme of conservation? With this overarching question in mind, my struggles with the best practices of interpretation were enacted in three themes: struggles with thematic development/story telling, difficulty making personal connections, and discomfort in using constructivist pedagogy.

Thematic Development: Conservation versus Humor. It was clear from the beginning of the study that my main goal and theme for my tours had to be conservation. Despite the mission change, the institution is still considered a conservation facility and the information we were given in our manuals about the animals includes how the animals are being conserved at the facility and in the wild. As was made clear in the prior section, my primary goal was to provoke visitors to feel connected to the institution after their tour in such a way that they would be compelled to take action for conservation. In examining the transcript of my tour, I was doing a decent job of articulating this theme/purpose toward the beginning of my tour but my mentions of conservation became much less frequent toward the end of my tour.

Most of my tours at the beginning of the summer included the following line as we entered the animal enclosures: “Each and every animal is here for a purpose for conservation and it’s my job to talk to you about that.” However, this was precluded by a safety speech and a discussion about the history of the institution rather than being stated at the very beginning to frame the rest of the tour.

As my early tours continued, they quickly became dominated by my “really bad jokes.” These were three jokes that I emphasized in a “self-deprecating” way. For example: “Time for another of my really bad jokes: Why can’t we play monopoly here? Because we have too many cheetahs!” At the beginning of the season I always ended my tour with the culmination of these jokes: “Here’s a joke I’m really proud of because I wrote it myself—you better laugh at it! Why do we have so many traffic jams? Because we have a big ‘crash’ of rhinos.’” This joke was followed by jibes at the visitors that the joke was just to test that they had been paying attention earlier when I told them a group of rhinos was called a crash.

At this point in the season, despite the fact that I was giving out solid information about our conservation programs throughout the tour, the underlying theme of the tour was being overshadowed by the corny jokes. Furthermore, in examining the surveys, this progression of jokes seemed to result in a large number of guests writing down that they learned “a group of rhinos is called a crash” in the open-ended section of the questionnaire (15 out of 43 answers). Additionally over half of guests wrote down some stand-alone fact about animals as what they learned during their tour, many of these being featured in one of my jokes.

I feel like with all my jokes and sarcasm I’m just making my tours into more of that attraction/theme park thing … which is exactly what I said I don’t want these places to be. But I do want people to like me. (Journal Entry, 6/15/2016).

They only remember the stuff that is incorporated in jokes. I guess I just need to make more jokes where the punchline is conservation. (Critical Friend Meeting, 6/12/2016)

Clearly I was concerned not only with making the tour enjoyable for visitors, but also the simple element of human nature to want to be liked by others. I feared that too much conservation may result in a bad taste in the visitors’ mouths. Therefore, I had to be thoughtful in how I changed my discussions of conservation by subtly shifting the organization of my tour. The first step was to improve my wrap-up speech in order to tie in the conservation theme. I did this by emphasizing the goal of my tour after the final joke about rhino crashes in the following line: “But more than the fact that I hope you learned a group of rhinos is a crash, I hope that you learned something about what we do for conservation.” The first day I added this line was also the first day that someone wrote that they “learned about conservation” on their survey.

My coworkers had a few suggestions for staying on the conservation theme, many of which focused on using humor to support conservation rather than simply being silly.

Me: I just find that whenever I talk about conservation it comes off as boring.

Leslie: Ask them questions to get engaged with conservation in particular.

Rachel: Reward them for what they already do for conservation.

Me: What I need is a joke about conservation, because I’m a pretty hilarious person in general … this just gets turned off whenever conservation comes up.

Rachel: Nine out of 10 wetlands have disappeared … hold up 10 fingers. Okay, now drop nine of them. How many are left? One. And what can you do with one finger? Well just about nothing except pick your nose. (Critical Friend Meeting, 6/15/2016)

In addition to providing some examples of using humor to advance conservation messages, Rachel also suggested emphasizing how unique the institution is throughout the tour. While I had been mentioning conservation, I hadn’t really been accentuating how special the place was to the practice of conservation. Thus, I made it my goal to tell guests a story where the institution was the main character and conservation was the theme. By the end of the season I felt like I had made strides toward this goal with a more in-depth discussion of conservation centers for species survival throughout the tour and emphasizing in my closing speech the number of programs done at the institution for conservation.

Personal Connections: How much is enough? One of the most frequently cited best practices in literature is to relate content to the lives of the visitor. Throughout the study I attempted to do this in small ways although I found this to be easier with school groups compared to the general public. Perhaps this was because of my experiences with teaching elementary students as part of my Ph.D. program and knowledge of the topics they were learning in school.

Today I started the tour by asking them what they already knew about animals with prompts like adaptations and habitat but I think I’d like to try to focus more on the connecting to previous knowledge as I continue on. Today it was just as simple as asking them about the kangaroo exhibit at the zoo to explain the salli-port and the kids remembered that the fences were “to keep the animals from getting into the parking lot” … too funny. (Journal Entry, 5/16/2016)

Despite these successes with school groups, I felt that my feeble attempts at relating to the visitor on my general tours were somewhat weak. For example, I compared the separation of animals between the enclosure as similar to brothers and sisters needing their own room. I also contrasted the cheetah’s claws to those of house cats.

My feeling of low efficacy for achieving personal connections with visitors was further supported by the surveys. The statement, “the material discussed by my tour guide related to my everyday life” was the lowest ranked item on the survey and this was a frustration of mine throughout the study.

And relating it more to them and their daily lives, that’s still lacking. Which stinks because it’s the number one best practice of interpretation, I just have no idea how to do it. Especially since these are rare and endangered animals … I feel like there shouldn’t have to be a connection to their daily life for them to care about animals! (Journal Entry, 7/21/16)

Even so, it appeared that guests were relating some of the material to their daily lives without my intervention, as evidenced by the videos of my tour. For example, the focal families would often reference prior experiences or other personal attributes:

Me: Their horns can get up to four feet long!

Child (to parent): That’s as tall as me … that’s cool! (Video Recording, 6/9/2016)

But are these self-initiated attempts to connect the material to their daily lives enough? Or should I be doing more to nudge them in this direction? This is a question I don’t think I ever quite reconciled over the summer, but my attempts at making my tours more discussion-based may have helped. Similarly, I believe that giving guests specific examples of what they could do in their daily life for conservation could be a good start, but throughout the summer I struggled to think of ideas that did not come off as cliché.

I think the one thing that is still lacking is the “What can you do for conservation?” and “Let me show you how,” partially because I don’t know what to tell them. (Journal Entry, 7/21/2016)

Me: Like, they already know recycling … that’s been shoved down their throats forever. And if I just list off things they can do, that’s still pretty preachy and impersonal.

Rachel: You just have to mention conservation along the way. Embed it subtly in everything. (Critical Friend Meeting, 6/15/2016)

Rachel also suggested rewarding them for what they already do as a means of connecting to them because people want to feel good about themselves. And it would still get them talking about conservation.

In sum, to reach the goal of connecting to the lives of visitors, I felt that given more time I could have restructured the whole tour and embedded more prompts for people to think of their own ways the material relates to them. In other words, my suggestion would be to encourage guests with the connections they are already making as they recall prior experiences with their families and reward them for making connections specific to conservation.

Constructivism: Fear of Silence. Finally, a few concerning factors of my tour became apparent after watching the video recordings. First, while I had been proud of the strides I had made compared to my first year in terms of making my tours more interactive, I found that most of my instances of “interactive” actually consisted of asking a bunch of rhetorical or trivia questions. For example: “Do you guys know what the camel stores in its humps?” or “Do you know how many neck bones a giraffe has?” While these did spark some interactivity in guests (many of the focal children proudly answered these questions to their parents or to me), they are shallow at best and do not relate to the central theme of conservation.

Additionally, I observed that many children on my tours were burnt out and restless by the end of the tour. This was particularly true when the animals were not very close to the bus and led to frustration that I had to carry the burden of being entertaining when the animals failed to do so.

Not the best tours today. Some of the kids were like “I’m bored” which is super discouraging and one asked me how much time was left and that made me sad but I don’t really know what else I can do to make it better because I do my song and dance and the jokes but if the animals aren’t there, they aren’t there … it’s just not hands-on and kids need the stimulation. (Journal Entry, 6/21/2016)

These realizations were met with more confusion and fear of opening my tour up to deeper conservation-focused discussion.

Starting to realize my tour is a lot more talking at them than talking with them … but it’s really hard. How to make it more constructivist??? Especially if the people don’t want to talk to you. Is just asking them questions they don’t have the answer to enough? I’m probably scared to lead a real meaningful discussion … like most teachers out there... Meaningful discussions are scary! You don’t know where they are going to go. Maybe I’ll give it a shot sometime. It’s really hard when you are rushed tho … because you have to either drive and talk and if you are stopped it’s usually by an animal and they want you to talk about it. (Journal Entry, 7/6/2016)

Clearly there was a fear of the direction that my tour might take if I opened it up to real meaningful discussion, particularly within the constraints of a two-hour, 30-minute time limit. Once again, the surveys supported this lack of minds-on learning since the statement, “My tour guide challenged me to think,” was consistently second lowest in agreement, just edging out the item about making connection to their daily life. Recalling from the literature on best practices that “mind-on” learning should be the goal, this prompted me to make some changes to my tour.

In one of my final tours of the summer, I tried to incorporate many of the components I had identified to make my tour better align with my goals. The main component I was going to try out was trying to have real discussions about conservation. I also tried to make it more interactive by incorporating a semi-hands-on activity throughout the tour.

Well, I tried the best I could. I started the tour with open discussion on what conservation means. People were fairly involved in that. I even did it before the safety talk. Then I handed out brochures and told them to make sure they checked next to the animal every time they found a baby—because that is what conservation success looks like for wildlife. So the whole theme was about conservation and I think I succeeded at that. I tried to make it more discussion rather than just rhetorical questions. A good example was when I didn’t just ask them what a camel uses its humps for but I opened it up and asked people to think about what traits a camel uses to survive in the desert. Most of the kids and some adults got involved. I even did the “pick your nose” conservation joke. (Journal Entry, 7/21/2016)

At this point in my tenure as a guide, I no longer felt any anxiety before my tours, but I was pretty anxious before this particular tour. I think this was partly to do with moving away from the auto-pilot speech and making myself vulnerable to the ideas of my guests. However, I found that one way to overcome this fear was just to treat “talking about conservation” as my new “shtick” instead of it being the jokes. I still told jokes, but they were better incorporated into the tour.

I think once you get into character that you are going to be serious about conservation it’s not as hard as I thought. And you can still make jokes and stuff, I think they still generally had a good time. Anyway, I felt proud of today’s tour. (Journal Entry, 7/21/2016)

I was most proud out of my tour when I was able to successfully represent how unique the institution is and emphasize how each animal fits into the bigger picture of conservation. And I felt most successful at doing this when I was able to open up to visitors and really get their thoughts about what conservation means and check for their understanding of the concepts. Adding in a more interactive element did seem to help the kids from getting bored so this may be an area worth developing for future tours at the institution.

Discussion

From my first day on the job over six years ago, the quality of my tours has changed tremendously. Starting off as a new guide, I was overwhelmed with learning the content, learning to drive the bus, and watching out for the safety of guests. As such, the sorts of insights I present in this paper represent many years of reflection and growth after these initial hurdles are overcome. However, despite the obstacles of entering into a new interpretive position, I believe my experience speaks towards the types of discussions that could reasonably be incorporated throughout the development of free-choice and informal educators. The implications of the study are discussed in relation to the major stakeholders in the field.

Implications for free-choice learning institutions include improving communication with and training of staff. Most notably, my journal entries and conversations expressed my frustration that the institution wasn’t providing me with a clear indication of what they wanted to be the goal of their education program. I would suggest that the mission and goals of interpretive tours should ideally be mediated between the front-line workers and the wider institution. More open communication and reflective evaluation practices could improve this. The self-study opened my eyes to the importance of a clear mission that permeates day to day business of the organization. National Association for Interpretation (2009) recommends that a mission statement be present in every aspect of interpretation. When this isn’t the case, guides are often left confused about what aspects they really should be focusing on. This is a common problem for organizations (Merriman & Brochu, 2009), particularly for young organizations or those with high financial burdens that necessitate additional sources of revenue that may stray from the mission. The findings of this study are not meant to criticize the mission of the institution I was working for in any respect but only to offer insights into how the mission is perceived from an inside perspective and propose ideas for improvement.

Assuming the institution has changing the behavior of its guests as part of its goals, this fundamentally changes training that should be used. We know from behavioral change research that awareness of environmental issues is not enough to get people to take environmental action (Heimlich & Falk, 2009). To do so, people must be provided with tools to take action and they must be empowered to believe their actions can make a difference (Ardoin, 2009). This requires advanced planning and clear statements of goals for the tour as well as explicitly targeting these behavioral change goals during the interpretation itself (Merriman & Brochu, 2009).

This is not always easy to do when the institution is also concerned with ensuring that their guests have an enjoyable visit and will want to return in the future. As illustrated by the results of my survey and the evolution of the script of my tour, strategies for mediating entertainment with conservation education should be a part of interpretive training. More detailed study should be done to specifically tease out the aspects of interpretation that visitors enjoy most and how these relate to the goals of the interpreter. This may be a difficult endeavor since it likely that satisfaction surveys (such as the one used in this study) are subject to social desirability bias that would cause them to rate their satisfaction as higher than it actually was (Crown & Marlowe, 1960).

The institution that I worked for allowed for a large amount of autonomy on the part of the interpretive guide. I believe this can be a positive aspect that allows the personalities of the interpreters to come through and better connect with guests. However, this can result in inconsistencies and a muddling of the message. I believe that regular constructive evaluation of staff programs may be one way to bridge this gap by gaining direct insights from visitors for how interpretation is being received (National Association for Interpretation, 2009). Evaluations could pinpoint inconsistencies but in a manner that allowed the interpreter to see how their practice actually affects the visitors rather than the institution using a completely uniform script.

The results of this study also have implications for interpretive guides to work with their institution to improve their practice and connect with visitors. For example, interpretation with a clear theme and story will result in more people connecting with this theme and thus connecting with the institution. Other best practices such as clear communication, relating to the visitor’s experience, humor, and discussion-based pedagogy also aid the visitor in making these connections. Similar to the development of pedagogy and content knowledge for classroom teachers, becoming an effective interpreter also takes time and practice and this can be enhanced with support from the organization as well as more focused practice on the part of the interpreter. For example, Bowling (2013) found that there were gaps in understanding and implementation of the best practices (interpreters used them about half of the time), but these differences were particularly striking between staff with academic training and/or prior work experience in education and those without. The author suggests that training in experiential and inquiry practices would probably help close this gap (Bowling, 2013). Additionally, Ivey and Bixler (2013) found that in training entry-level naturalists, the desired content knowledge (ecology, ornithology, and conservation biology) was readily available, but materials pertaining to communication skills were not. The authors assert that it is important for institutions to provide their staff not only with support regarding their content but also about communication, people, and program planning (Ivey & Bixler, 2013). Throughout my study, I found that my own efficacy for connecting with guests was low. As such, specific training and repetition of the best practices may aid in building mastery of these sorts of specific skills that can be learned over time (Bandura, 1982).

In addition to training, I believe that interpretive guides could also benefit from more communication between practitioners. Communication with other guides can help by sharing practices that work with each other. During this study the conversations I had with coworkers about my practices helped push and improve my own practice. Opportunities for this kind of dialogue could be encouraged or facilitated by the institution.

Finally, as an implication for the field of free-choice education research, I would argue for the value of doing more self-study and ethnographic research. The benefits of self-reflection have been touted in the field of education and these benefits are equally viable for informal educators to improve their practice and share their experiences with others. I believe my own practice was improved as a result of this study and the insights were also shared with management of the institution I worked with to improve the organization as a whole and provide better support to their employees. Additionally, the self-study methodology helps to illustrate the subtle nuances of emotion and internal states that cannot be measured by surveys and observation. Directly addressing these sorts of feelings and tensions helps to better understand our own practice and the practice of others.

Conclusion

As a result of this study, a few significant insights emerged. Perhaps the most central of these was the importance of defining the goals and purposes of any form of interpretation. However, simply defining these goals is not sufficient for achieving them. The accomplishment of these goals may require compromises with perceptions about what is entertaining for guests as well as stretching the comfort zone of the interpretive guides themselves. Making the sort of deep connection to visitors required to reach these goals may be difficult in such a short period of time, but the development of best practices can help. For example, humor and confidence of the interpreter can go a long way as well as also allowing visitors more space to make their own connections. Becoming a teacher is not easy. Adopting a more constructivist pedagogy in free-choice education represents a real struggle for interpreters. This type of teaching is not utilized often in informal settings and this self-study illustrated the reality around our fears about seeming vulnerable to guests. More support and training for using constructivist teaching methods may help guides feel more confident about this practice. It is my hope that this self-study sheds light on some of the real-life challenges of enacting the best practice of interpretation and provides some areas of focus for improvement in the future.

References

Ardoin, N. (2009). Behavior change theories and free-choice environmental learning. In J.H. Falk, J.E. Heimlich, & S. Foutz (Eds). Free-choice learning and the environment (pp 57–76). Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37 (2), 122–147.

Beck, L., & Cable, T.T. (2011). The gifts of interpretation: Fifteen guiding principles for interpreting nature and culture (3rd Ed.). Urbana, IL: Sagamore Publishing, LLC.

Bullough, R., & Pinnegar, S. (2001). Guidelines for quality in autobiographical forms of self-study research. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 13–21.

Burris, A. (2017). A child’s-eye view: An examination of point-of-view camera use in four informal education settings. Visitor Studies, 20 (2), 218–237.

Bowling, K.A. (2013). The understanding and implementation of key best practices in national park service education programs. Journal of Interpretation Research, 18 (1), 83–88.

Crowne, D.P. & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathy. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24 (4), 349–354.

Dinkelman, T. (2003). Self-study in teacher education: A means and ends tool for promoting reflective teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 54(1), 6–18.

Falk, J.H. & Dierking, L.D. (2013). The Museum Experience Revisited. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press Inc.

Falk, J.H., Reinhard, E.M., Vernon, C.L., Bronnenkant, K., Heimlich, J.E., & Deans, N.L. (2007). Why zoos and aquariums matter: Assessing the impact of a visit to a zoo or aquarium. Association of Zoos & Aquariums. Silver Spring, MD.

Glaser, B.G., & Strauss, A.L (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New Brunswick: AldineTransaction.

Grenier, R.S. (2009). The role of learning in the development of expertise in museum docents. Adult Education Quarterly, 59 (2), 142–157.

Hamilton, M.L, Smith, L., & Worthington, K. (2008). Fitting the methodology with the research: An exploration of narrative, self-study, and auto-ethnography. Studying Teacher Education, 4 (1), 17–28.

Heimlich, J.E. & Falk, J.H. (2009). Free-choice learning and the environment. In J.H. Falk, J.E. Heimlich, & S. Foutz (Eds) Free-choice learning and the environment (pp 11–22). Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Hunter, J.E. (2012). Towards a cultural analysis: The need for ethnography in interpretation research. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17 (2), 47–58.

Ivey, J.R. & Bixler, R.D. (2013). Preparing to be an interpretive naturalist: Opinions from the field. Journal of Interpretation Research, 18 (1), 89–96.

Knapp, D. & Benton, G.M. (2004). Elements to successful interpretation: A multiple case study of five national parks. Journal of Interpretation Research, 9 (2), 9–26.

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817–869). Springer Netherlands.

Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry (Vol. 75). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Merriam, S.B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, California: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Merriman, T. & Brochu, L. (2009). From mission to practice. In J.H. Falk, J.E. Heimlich, & S. Foutz (Eds) Free-choice learning and the environment (pp 77–86). Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

National Association for Interpretation (2009). Standards and practices for interpretive methods. Retrieved from: https://www.interpnet.com/docs/BP-Methods-Jan09.pdf

Pearce, J.A. & David, F. (1987). Corporate mission statements: The bottom line. Academy of Management Perspectives, 1 (2), 109–116.

Rabe, M. (2003). Revisiting ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ as social researchers. African Sociological Review, 7 (2), 149–161.

Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. American Psychological Association, Inc, 55 (1), 68–78.

Skibins, J.C., Powell, R.B., & Stern, M.J. (2012). Exploring empirical support for interpretation’s best practices. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17 (1), 25–44.

Stern, M.J. & Powell, R.B. (2013). What leads to better visitor outcomes in live interpretation? Journal of Interpretation Research, 18 (2), 9–44.

Stern, M.J., Powell, R.B., McLean, K.D., Martin, E., Thomsen, J.M., & Mutchler, B.A. (2013). The difference between good enough and great: Bringing interpretive beset practices to life. Journal of Interpretation Research, 18 (2), 79–100.

Tilden, F. (1957). Interpreting our heritage. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

UNESCO-UNEP. (1978). The Tbilisi Declaration: Final report intergovernmental conference on environmental education. Organized by UNESCO in cooperation with UNEP, Tbilisi, USSR, 14–26 October 1977, Paris, France: UNESCO ED/MD/49.

Visscher, N.C., Snider, R., & Stoep, G.V. (2009). Comparative analysis of knowledge gain between interpretive and fact-only presentations at an animal training session: An exploratory study. Zoo Biology, 28. 488–495.