Journal of Interpretation Research

Volume 22, Number 1

Interpreting Terrorism: Learning from Children’s Visitor Comments

Mary Margaret Kerr

Professor, Psychology in Education

University of Pittsburgh

230 South Bouquet Street, 5911 WWPH

Pittsburgh, PA 15260

mmkerr@pitt.edu

412-648-7205

Rebecca H. Price

PhD student, Administrative and Policy Studies

University of Pittsburgh

Constance Demore Savine

Instructor, Administrative and Policy Studies

University of Pittsburgh

Kari Ifft

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Mary Anne McMullen

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Author Note

We acknowledge with gratitude our colleagues at the Flight 93 National Memorial: Barbara Black, Donna Glessner, MaryJane Hartman, Jeff Reinbold, Adam Shaffer, Kathie Shaffer, and Brendan Wilson, who introduced us to this work. We also thank Sandy Watson, who assisted with field-testing, and Cole Cridlin, who assisted with the figures included here.

Abstract

Thousands of children visit memorials and other dark heritage sites each year, yet researchers have rarely studied their experiences. Faced with limited prior research, interpreters at terrorism-related sites grapple with especially serious and unanswered questions about how best to engage young visitors. To address these concerns, the staff of the Flight 93 National Memorial, erected at the crash site of an airline hijacked on September 11, 2001, partnered with an interdisciplinary team of researchers. The team studied children’s post-visit comments at the Memorial, adapting the content analysis methods of prior researchers who studied visitor comments, logs, and books. Children exhibited patriotism, grateful remembrance, emotional realizations, and a sense of place as they struggled to make meaning of the events. These findings led to relevant and understandable interpretive activities, which now comprise the Junior Ranger program for young visitors. The paper suggests implications for future research on interpreting terrorism-related events.

Keywords

Flight 93, interpretation, children, visitor comments, visitor log, memorials, meaning-making, interpretive themes, 9/11 memorial, terrorism

Interpreting Terrorism: Learning from Children’s Visitor Comments

Thousands of children visit memorials and other sites of painful heritage each year. Research on the content of children’s interpretation at such heritage sites rarely appears, as noted by Sutcliffe and Kim (2014). A growing addition to the destination roster includes sites honoring victims of terrorism. For example, more than 100,000 schoolchildren visit the National 9/11 Pentagon Memorial annually (A. Ammerman, personal communication, August 30, 2016). Yet, the research literature remains surprisingly silent about young visitors’ encounters, leaving interpreters with little empirical guidance (Frost & Laing, 2016; Kerr & Price, in press; Kerr & Price, 2016; Poria & Timothy, 2014; Small, 2008; Sutcliffe & Kim, 2014).

We encountered firsthand this difficulty at the Flight 93 National Memorial, which commemorates the deaths of 40 passengers and crew whose plane terrorists hijacked on 9/11. Here, the interpretation dilemma immediately became apparent to the staff. Jeff Reinbold, then Western Pennsylvania National Park Service (NPS) Superintendent, put it this way:

The kids want to know why their parents are crying. It’s a very adult story. And we’re trying to understand how best to explore ways to tell this story to young children and prepare them and their parents for a visit to the memorial and what may be a very emotional experience. (as cited in Hornick, 2012)

NPS rangers continue to wrestle with multiple challenges. First, the Flight 93 National Memorial is new—its visitor center opened in 2015. No child-specific exhibits or interpretive tours yet exist. Yet various intensely fraught interactive exhibits invite children’s participation. These include facsimiles of on-board telephones featured in one exhibit. Visitors may pick up the phone and listen to the last calls of doomed passengers. Naturally, safeguarding young visitors while engaging them in meaningful visits raises interpretive concerns. To address these issues, the NPS staff turned to our interdisciplinary team of developmental psychologists, educators, and mental health specialists to help develop its Junior Ranger Program for children aged 6 to 12 years. Three overarching ideas previously adopted by the NPS would guide our work: a) A Place of Reflection, b) Honoring the Heroes, and c) A Call to Action.

The urgent need to interpret these ideas for children in a booklet containing appropriate activities led us to consider readily available data to inform our work: visitor comments at the site. Collected since 2003, visitor comments provided an accessible glimpse of young visitors that we could use without delaying the development of the much-needed interpretive program. This paper describes how we pursued our research questions: What could children’s comments tell us about their views of the events of 9/11 and the site itself? How might we then incorporate these insights into a Junior Ranger program? This paper also discusses the themes, or primary messages, we identified through our analysis and interpretation of children’s comments. As terror events continue to play an unfortunate role in our society, we share our findings to help others interpret these tragedies for children.

To provide context for our data collection approach, we first review how others have studied archived visitor comments, and then discuss the interpretive importance of children’s meaning-making.

Relevant Literature

Visitor comments appear in multiple forms across museums, memorials, and other tourist destinations around the world. Typical formats include handwritten visitor logs (sometimes called comment books), handwritten cards left in collection boxes or posted for public view, comments entered at a computer terminal, and online comments left on travel-oriented websites (see for example Coffee, 2011; Livingstone, Pedretti, & Soren, 2001; Macdonald, 2005; Munar & Ooi, 2012; Price & Kerr, 2017). Despite their proliferation, “comment books are certainly under-used and under-analyzed” by researchers (Coffee, 2011, p. 166). A viable approach for understanding visitor perspectives, accounts of visitor comments have appeared in multiple forums and disciplines, and for different purposes (see for example Coffee, 2006; 2011; Livingstone et al., 2001; Macdonald, 2005; Miles, 2014; Morris, 2011; Pekarik, 1997; Reid, 2005).

While not without their limitations, visitor comments may capture unfettered views distinctly different from more common measures, including surveys, time and attention studies, and interviews (Coffee, 2011; Macdonald, 2005). Visitor comments at memorials and other “public exhibitions archiving war or human loss” archive human responses to controversial installations (Morris, 2011, p. 243). Munar and Ooi (2012) found surprising emotional honesty in online comments about Ground Zero, site of the 9/11 World Trade Center attacks in New York City. Discussing visitor comments at a sweatshop exhibit, Alexander (2000) suggested that visitors use comments to “talk with” curators of exhibits, broadening the exhibit’s interpretive message and “molding it to their experiences and interests;” they “make meaning for themselves from it” (p. 89). Price and Kerr (2017) studied on-line comments to understand how adults view children’s behavior at war memorials.

Researchers typically focus on adult comments. Their analytic methods fall along a spectrum, with some scholars using “intelligent critical reading” (Macdonald, 2005, p. 123) and then describing their general impressions and conclusions (Alexander, 2000) or offering a general “textual analysis” (Ferguson, Piché, & Walby, 2015). Others adopt more structured categorical tallies, first sorting, and then counting the frequency of specific words or phrases (Livingstone et al., 2001). Lastly, some initially categorize or sort comments then choose more interpretive methods to identify emergent themes that reflect visitors’ meaning-making (Macdonald, 2005).

With our study, we allowed children who were not the beneficiaries of formal interpretation to “talk with” us through their comment cards. We listened to their voices in order to understand their personal meaning-making of the tragic events commemorated, but not formally interpreted, for them at this memorial site. By meaning-making, we refer to the personal meanings that children attributed to their visits. Because the literature to date has not delved into children’s meaning-making at sites of terrorism, we reasoned that this initial exploration of children’s own words would allow us to gain insight into their encounters, thereby informing the design of the Junior Ranger activities. In this way, we hoped to identify interpretive activities with provocation likelihood: the ability to provoke thought (Ham, 2013). First, we needed to understand what mattered to children about the Flight 93 crash site, so that we might design interpretation relevant to them. Second, we studied their word choices and ideas to discern what interpretive concepts and language would, for them, “be easy to understand and process” (Ham, 2013, p. 124).

Methods

Artifacts Studied

In 2003, the Flight 93 Memorial site began offering comment cards for visitors (A. Shaffer, personal communication, February 18, 2015). A display board allowed visitors to post their comments for others to read. Each week, staff or volunteers collected the cards for archiving by the National Park Service. Our investigation included an analysis of comment cards authored by visitors in 2003 and 2004. We chose these because they were easily accessible, offered a perspective not yet influenced by formal interpretation (at that time not available at the site), and could be compared with other sources such as memorial tributes that children sent or left at the site. (A brief description of comments and other tributes from 2001–2006 appears in Kerr & Price, in press.)

Because the comments were left in a public space with no expectation of confidentiality, they are considered “abandoned public property” under NPS regulations, according to the Flight 93 National Memorial Chief of Interpretation and Cultural Resources (B. Black, personal communication, December 13, 2013). Researchers who register with the NPS may study the cards and other abandoned public property archived at the memorial. Our university’s Human Protection Office determined that this study did not necessitate approval as human subjects research because we had no human interactions and studied publicly available information. Nevertheless, we chose not to report names or other personally identifiable information.

Fearing that a less-than-systematic review of the comments might lead us to misinform the children’s interpretation program (see Coffee, 2011), we sought the most appropriate methods for analyzing the comments. Following methods outlined by MacDonald (2005), we first read all comment cards to get a sense of the comments as a body of evidence. Next, we considered how we might identify the cards authored by children ages 6 to 12 years (the age group targeted for our Junior Ranger booklet). This selectivity was necessary because the cards were available to visitors of all ages. This identification process remains a challenge recognized by other researchers:

Making the task harder is the fact that information about those who write in visitor books is usually extremely restricted or even non-existent. While this poses an interpretive challenge, however, it does not make visitor books worthless as research sources. (Macdonald, 2005, p. 123)

Two research team members with extensive experience in deciphering children’s handwriting took the assignment of selecting comment cards. These researchers are educators with nearly 60 years combined experience with children in the targeted age span. Naturally, we included comments on which children provided their names and ages. When the child’s age did not appear on the card, we followed a multi-step process. Specifically, we followed the guidance of prior researchers (see Alexander, 2000; Macdonald, 2005) and considered the signature and age (when provided), handwriting style, spacing, spelling, word choices, and any images like hearts or drawings (if included) to infer if the author was a child. Two team members examined characteristics such as the size and shape of the letters, and the arrangement of words and phrases throughout the writing. Because children can lack fine motor skills and use a narrower vocabulary than adults use, the team recognized properties of the writing such as the formation and spacing of letters, and syntax likely written by children. We eliminated any comment card whose writing clearly appeared adult-like in style, vocabulary, or syntax. When we could not agree, a third researcher with 30 years’ experience as an art educator/art therapist evaluated the writing, using the same criteria. Lastly, we shared a sample of our comment cards with our larger research team for their assessment. This multidisciplinary team included individuals who had not sorted the comment cards: five psychology students, a faculty member whose expertise is children’s literacy, a research and instruction librarian, and another K-12 educator.

As Macdonald (2005) suggested, we employed triangulation of sources (see Denzin, 1978; Patton, 1999) to validate our identification of comments attributable to children. Specifically to validate these findings, we studied other children’s artifacts left during the same period. These included tribute objects (e.g., toys, crafts, and jewelry with notes attached), artwork with and without text, and notes. Our analysis of these artifacts revealed similar messages and styles of writing, thus offering validation that children wrote the comments cards we studied (see Kerr & Price, in press).

Data Analysis

Prior researchers established the use of content analysis to study open-ended responses from visitors at memorials and other painful heritage sites (Coffee, 2006; Macdonald, 2005; Miles, 2014; Stone, 2012). We adopted a similar analytic approach, informed by qualitative researchers in the social sciences (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007; Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2013).

In all, 106 comments authored by 108 children comprised our sample (three children co-signed one card). Cards showed date stamps of November 3, 2003, through July 29, 2004. Eighty-one cards included names, allowing us to surmise that females authored 48 of the comments and males authored 33 comments. Because so many comments were a popular phrase at the time as described below, it is difficult to discern the age of their authors. In contrast, phrases that are more complex appeared in approximately 20 percent of the comments, suggesting that their authors were pre-adolescents or adolescents. Ten percent of the comments appeared to be written by children under the age of 7. In some instances, these young children appeared to copy what an older sibling or parent had written. We determined this because we found the cards together with the same family names and date on them. All comments were written in English. Comments varied in length, with the briefest consisting of only one word (God) and the handwritten date. The longest comment contained 184 words and included a poem, which the child composed and intended for display in the not-yet-constructed visitor center. We first transcribed each comment as a separate entry. To preserve their authenticity, we recorded the comments verbatim, with original spelling, grammar, capitalization, and punctuation.

Next, we uploaded all comments into a qualitative data analysis computer program for the purpose of line-by-line coding (Veal, 2006). Two researchers (the first and third authors) began our coding by using 41 initial codes. These initial codes derived from our ongoing review of children’s tributes in the Flight 93 Memorial archives (see Kerr & Price, in press). To describe the tribute objects we photographed, we initially developed a codebook based on our preliminary review of the text, images, and types of objects. These codes include (a) expressions of emotion (e.g., sad, happy, fear, and anger); (b) references to the passengers and crew (e.g., victims, specific names, hero/ines, and pilot); (c) religion (e.g., references to God or religious practices such as prayer); (d) date references (e.g., 9/11 or September 11); (e) remembrance (e.g., remember, never forget); (f) thanks (e.g., thank you, grateful); (g) references to one’s country (e.g., America, American, USA, other countries); and (h) references to the plane (e.g., United, Flight 93).

As two analysts coded, we wrote iterative researcher memos focusing on key comments (Charmaz & Mitchell, 2001; Saldaña, 2009). After one author coded all comments, another author independently coded all of the comments to establish inter-coder consistency. We discussed and resolved any discrepancies until we had consensus, and then examined the comments repeatedly to identify new codes and derive patterns across the comments. Specifically, we counted specific words, looked for clusters of words that appeared frequently, and searched for overarching meaning, which we considered themes (Macdonald, 2005). Lastly, we verified our process and interpretations with the second author and with the interdisciplinary research group described above. This process consisted of sharing our codebook and resulting coding spreadsheets in team meetings, seeking members’ interpretations of the coding, and making adjustments in our descriptions of the key concepts and themes.

Findings and Applications

To provide an overall picture of the children’s comments, we begin with a general description, including counts (Sandelowski, 2001). The most frequent codes we applied were religion (56), the plane (30), gratitude (28), remembrance (21), and the site (13). Similar to the cards penned by adults, many cards implicitly addressed the passengers and crew. This excerpt illustrates how we applied the codes:

Thank you for your Bravery (gratitude). Flight 93 changed any peoples Lives (the plane). You will always be in my heart! (remembrance) God Bless you (religion) You fought well!

As seen in this example, we present the comments verbatim. Taken together, the comments revealed four of the five overarching codes (as indicated by italics). As explained above, we continued the process of coding and simultaneously interpreting data until major themes or concepts emerged. By using the literature to support or challenge the themes that surfaced, we analyzed our findings to determine how children made meaning of their visit. These themes are illustrated and discussed next.

God Bless America, American Mantra

The simplest and most frequent expression from the children was the phrase God bless America or God bless the USA, written alone or with other text, as excerpted from one card above.

This phrase also appeared frequently in drawings we examined (Kerr & Price, in press). Children’s communication of this phrase makes sense in light of the context of the event and the prevalence of the phrase God bless America during the years following 9/11. In the political discourse and news media of post-9/11 America, God and country often remain strongly intertwined. The phrase “God bless America” dominated public discourse to a greater degree in the early 2000s than at any time since 1880 (Kaylor, 2013). Because of the frequency with which these messages were communicated, we found children’s connection between God and country to be an overarching theme.

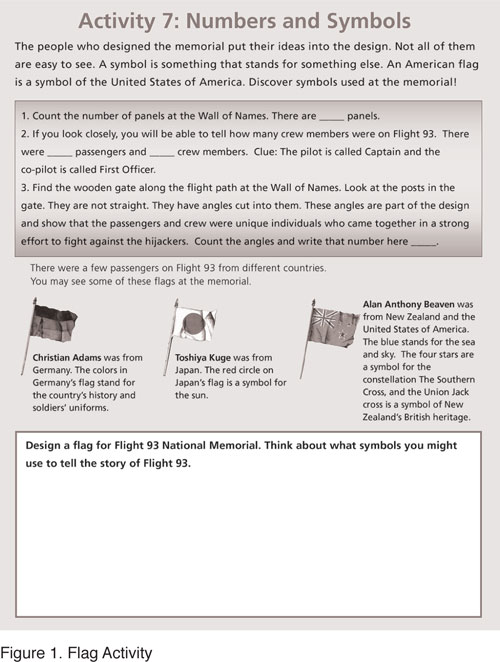

To more fully understand this emergent theme, we turned to the literature about children’s political and religious socialization. In what some consider the seminal study in children’s political socialization, Easton and Hess (1962) found that by age 7, children have grasped their identity as Americans, and they firmly and emotionally attach to their nation. They also noted that until “ages 9 or 10 [children] sometimes have considerable difficulty in disentangling God and country” (Easton & Hess, 1962, p. 238). This conceptualization aligned with hundreds of children’s drawings, letters, and notes we found that referred to America or the USA, most often drawn in red, white, and blue, many of which also included the words God bless followed by America, the USA, the flag, our country, our people, or our nation (Kerr & Price, in press). Even very young artists communicated nationalism symbolically through images of flags or use of red, white, and blue. This finding suggested to us that the Junior Ranger booklet incorporate national symbols when appropriate because these symbols would resonate with children. In response, we included an activity that prompts children to look for flags flying at the Memorial, including flags from other countries. Another activity encourages children to draw a flag with symbols that honor the passengers and crew. Figure 1 illustrates these ideas.

Children’s Personal Meaning-Making

At all stages of our lives, we as humans attempt to organize our experiences in ways that make sense to us and to our lives (Emde, 2003; Saltzman, Pynoos, Lester, Layne, & Beardslee, 2013). Successful interpretation takes such personal meanings into account (Ham, 2007; 2013), so we searched the comments for words and concepts that characterized how children grasped what took place and expressed their feelings about the event.

Understanding children’s personal meaning-making merited attention for another reason. For young children, meaning-making (often expressed through imagery, imaginative play, or stories) plays a role in managing frightening or stressful situations (Saltzman et al., 2013). Stone (2012) reported on this phenomenon at the 9/11 Tribute Center:

One of the most poignant “emotional markers” displayed in the Gallery is a small hand-made heart-shape card which had been designed and coloured with crayons by a pre-school boy whose father … died instantly. The emotive message on the card from his young son simply reads: To Daddy, I hope you are having a great time in heaven. I Love You. (pp. 85–86)

This grieving child derived meaning and possibly reassurance from his image of his father enjoying Heaven. In our case, the attempt to make meaning of 9/11 revealed itself in even the comments written by the youngest children. One child simply drew an overturned airplane and poignantly added, “Dear men I miss you I love you I know the plane crashed.” This focus on the immediate event is typical of young children who lack the cognitive ability to consider an event more abstractly (Rosenblum & Lewis, 2006). What follows are examples of how other young visitors made meaning and the themes that emerged from our analysis.

Grateful remembrances. As Gordon, Musher-Eizenman, Holub, and Dalrymple (2004) uncovered in letters to first responders at the World Trade Center, children expressed gratitude to the Flight 93 passengers and crew for their heroism and sacrifice. Girls, aged 8 and 10, signed the first two comments below. The other comments were unsigned.

- “Thank you for helping our country’s future by landing in this feild. It is a great opportunity for me to be here personaly. May god bless your souls.”

- “Thank you so much for saving your life for us I really do appreciate what you did for me.”

- “Thank you & God bless! We will remember, never forget! Thank you!”

- “Thank you for courage. You All will be greatlly missed And Allways remembered.”

- “Visiting Shanksville was a great experience for me. Everyone has been so kind putting up things to remember the people they love. You have done a great thing for these people. God bless you.”

- “I had a good day. I through a coin. I made bouquets. If you were here thanks for your sacrafice. god bless everyone. Thank you.”

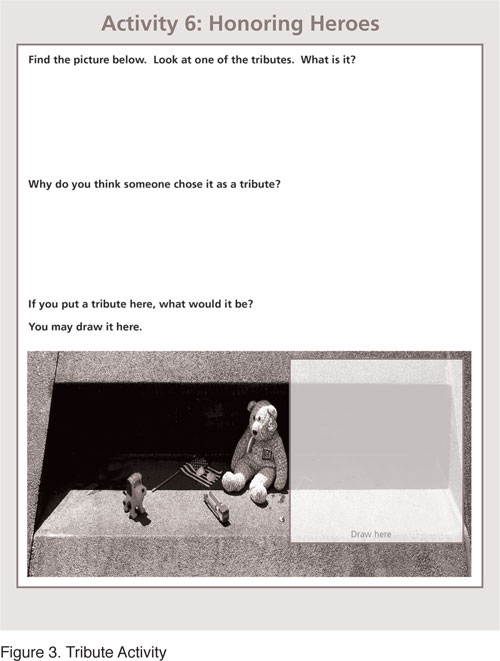

Comments such as these influenced our decision to include a tribute activity as a tangible symbol of the gratitude expressed by prior young visitors (see Brochu & Merriman, 2008; Ham, 2013; Larsen, 2003). Linking tangible objects in this way to intangible meanings provokes theme-based thoughts (Ham, 2013). In this case, tributes symbolize gratitude and remembrance, thereby reinforcing one of the three interpretive ideas guiding our work, A Place of Honor.

Emotional realizations. Several notes, poems, and questions suggested that young visitors wrestled with their feelings at the site. For example, some comments echoed several ideas and ensuing emotions. As Eisenberg, Fabes, and Spinrad (2006) noted, young adolescents possess the cognitive and emotional capacity to experience multiple emotions and ideas simultaneously. We see this capacity evidenced when a girl expressed both confusion and sorrow:

I’m very sorry for the people who have died even though I donot know them.

I’m so sorry! I cried when it happend but I’m over it know. And I don’t know why those people took over.

Another girl commented, “I feel sad. But then I feel Happy for the men and women that died, that the did a brave thing.”

As one might expect, some comments suggested more mature meaning-making, as children grappled with the unimaginable and then came to realize what happened aboard the plane. The comments also reflect young adolescents’ development of empathy, which requires that one have the cognitive ability to think abstractly and consider how others might feel (Rosenblum & Lewis, 2006). To illustrate, a girl wrote:

As I look over the feilds and try to stand all the leters, writings and so on I realise that this is life and a hard part of it. I wish I could have brought back the life’s of these people.

Similarly, a teen described how visiting the memorial inspired a new realization of how the tragedy affected her family. Then, she turned her thoughts to the passengers:

You never really realize something as tragic as this until you actually visit the site and see the memorial. My mom is from this town and this is such an awful thing. It has affected our family, yet brought us closer together. I cannot imagine the terror of the people on the flight. What they saw & were feeling. I think this would have been awful if these heros had not stepped in. Now that I have been here, seen it, and felt the emptiness. I can not believe it! It is amazing and emotional, but I think this has been a wake up call for America.

Lastly, another teen offered a retrospective reflection:

I have much respect for what this Memorilal stands for. I am now 14 year old and when this had happened I was 10 years old and I really did not understand what had happened so now that I have had the chance to learn more about it I understand what had happed Ive got to see this memorial and I Just wanted to thank all the people that had Joned in and helped to make this able to see and thank you to all those heros

The comment cards echoed the centrality of children’s need to grapple with whatever thoughts and feelings they experienced during and after their visit. In his chapter on interpretation at painful heritage sites, Uzzell (1998) observed:

Heritage sites and museums are not necessarily just places for the reconstruction of memories, but settings where visitors come to negotiate cultural meaning … a place where people come to understand themselves. If museums and other heritage sites are to be socially meaningful then they will be about the visitor. (pp. 4–5)

The Place of Reflection interpretive concept afforded the opportunity to include activities for children that allowed them to express themselves in different ways, as Machlis and Field (1992) and Tilden (2009) emphasized in their guidance on interpreting for children. Another Junior Ranger activity invites children not only to observe, but also to draw or write their thoughts. Hand-drawn images of two comment cards accompany an invitation: “Maybe later you will want to write a message to share with others.”

A sense of place. Thirteen comments offered children’s perspectives on the temporary memorial site itself.

- “I love this site and memorial. Our school sent something in last year when they came and everyone’s name in the school was on it, but I didn’t get to sign it. I just want to be able to show that I helped out too.”

- “We are very amazed at what we saw and read. The crash site is very sad and touching to see. I feel really bad for all those people on the plane. Love, Kyle Sorry God bless”

- “I think the crash site is very wonderful because it honors the people who gave thier lives for strangers and people who they know. And I like all of the stones and the others things here.”

Some young people offered their recommendations as if they were addressing the Memorial staff:

- “Us, I think you should tell the exact place where it crashed.”

- “I think you should make this field a big memorial park so people can come to see their heros that died on flight 93 and you should have peoples own sight for their families”

Children’s sense of place (Sobel, 1993) revealed itself in these comments. Suggestions about improving the crash site as a place of reflection reveal a possible link with studies showing that children and adolescents seek preferred spaces for cognitive restoration when emotionally distressed (Korpela, 1992; Korpela, Kyttä, & Hartig, 2002). In addition, suggestions for how to create or improve the memorial conveyed children’s desire to take constructive action, a phenomenon documented in earlier studies of children’s resilience following the events of September 11, 2001 (Brown & Goodman, 2005; Phillips, Prince, & Schiebelhut, 2004).

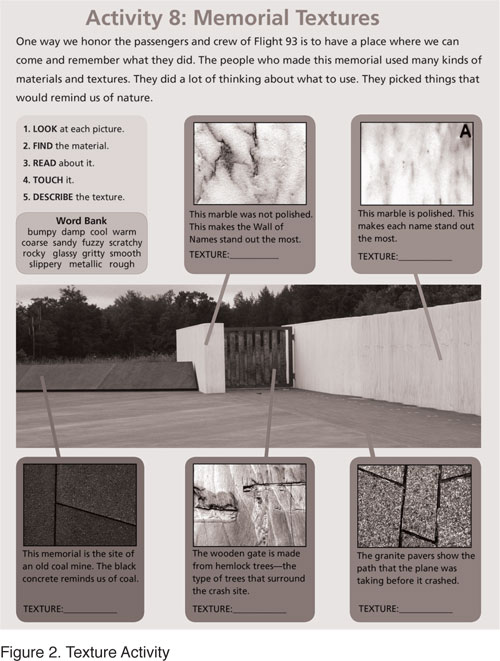

In response to these place-oriented comments, we created activities encouraging children to explore architectural features of the memorial. Inviting children to interview their families or the park rangers about the construction of the memorial became one of the activities included under the booklet section entitled, “Call to Action.” Knowing that many children explore tactilely (a phenomenon we observed many times at the site), we designed a “memorial textures” experience for children to learn the symbolism of various stone surfaces by exploring their textures. Offering still another way for children to reflect and honor those lost, these hands-on activities reinforce the interpretive themes, accommodate different learning styles (Beck & Cable, 2002), and link tangible objects to the abstract meanings of the Memorial’s design (Larsen, 2003). For example, one activity shown in Figure 2 invites children to feel the polished marble on which the passenger and crew names are engraved, in this way tactilely exploring how the architecture honors the heroes.

Validating Our Interpretations

To verify our approach to designing the interpretive activities (see Pinter, 2014; Pinter & Zandian, 2014; Pinter & Zandian, 2015), we needed children’s views. Accordingly, we arranged to field test our initial Junior Ranger booklet with 65 schoolchildren in grades 4 and 5 (ages 9–12 years). When they arrived at the Memorial, we invited them use the booklets and to write or tell us their feedback as they worked through all of the activities. After their visit, we gathered and scanned each booklet. We then read and summarized all of their comments. Here are examples of the students’ verbatim feedback:

- “If your trying to put this toward little kids I’d say have less writing. For our age it was fine.”

- “I would add a word search and other activities like that.”

- “Hide fun items in cool places so kids will go there.”

- “Harder activities for older children — Something where you interact with your surroundings, besides those things it was fun.”

- “Make the activity part of #8 more prominent (I saw it, but others might not)”

- “The activity where it showed different times and what happened at that time was a little confusing. I had gone 2 times before the field trip and I think I learned the most this time because of the booklet.”

Our next task was to revise several activities to make them more appealing. Then, we field-tested the revised individual pages affixed to clipboards, with families visiting the Memorial on two weekends. After children returned the pages, we informally asked them to tell us what they liked or did not like about the activity and took notes on their suggestions. Given that the activities were designed for 6- to 12-year-olds, with three levels of activities for each theme, this provided us with some feedback on each level. Although it extended the development work a few months, this pilot testing helped us improve each activity. For example, children found the explanation of the last minutes of the doomed flight quite confusing. Yet, this activity is important to the interpretive message of A Call for Action because it highlights the actions of the passengers and crew who stopped the terrorists from reaching their intended target in Washington, DC. Field-testing different versions of this page helped us understand how to convey time in a way that young visitors could comprehend. In another revision, we defined difficult words (e.g., “archeology”) on a page explaining the symbols on the National Park Service arrowhead. In a third revision, we added a drawing space to a page that had called only for written answers.

Our experience taught us that field-testing interpretive materials for young visitors is an essential step for any site that receives many children and that may not have the resources to provide individualized guidance during a visit. As one of our team observed, “We loved that activity, but the kids didn’t! Thankfully, we learned that before we went to the printer.”

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

The urgent need for interpretation at a new and emotionally demanding site fueled this study, and it led us to unearth children’s insights. As we studied children’s comments, we tackled several obstacles.

First, by necessity we studied a convenience sample of comment cards by visitors who chose and who had the ability to complete them. As others have noted, visitor comments rarely include personally identifiable information, with the possible exception of hometown. Addressing this barrier, we painstakingly reviewed each card and compared our analyses with other data sources. Such a process is inevitably imperfect and often impractical. While federal regulations may prohibit asking for such personal identification at National Parks, other sites might add the option for a visitor to self-identify their age or age range.

The comments studied represent the site prior to interpretation. However, they also represent years in which some children could have recalled the events of 9/11. Those children may have a different perspective from children of today, who are distanced by time from this disaster, and for whom terrorism constitutes an unfortunately more common occurrence.

With comment cards as our only source of data about their authors, we cannot ensure that our interpretations accurately represent children’s meaning-making (Bruner, 1991), nor can we consider their perceptions in the context of their age or developmental level. Yet, our findings are verified by comparison with children’s artwork and other tributes left at the site (see Kerr & Price, in press; Koc & Boz, 2014). At the same time, to ensure that we understand children’s perspectives ultimately requires that children themselves participate fully in research. After all, “children are the primary source of knowledge about their own views and experiences” (Alderson, 2000, p. 287). Lastly, our sample almost certainly represents predominantly American, English-speaking children, limiting its relevance to other cultures whose children should be represented in future studies.

Despite its limitations, the study showed that analysis of a common activity—leaving visitor comments—may facilitate our understanding of young visitors’ encounters. Informed by their voices, we designed activities for children ages 6 to 12 years. We also sought reasonable constructive outlets for children’s emotions and behaviors, because “any interpretation which excludes these dimensions is less likely to be effective” (Uzzell, 1998, p. 2). To ensure that the activities continue to be effective with today’s visitors, we discuss the program with the NPS rangers every few months. In these conversations, we jointly plan revisions to pages that children do not find appealing.

Conclusions

Dec (2004) described the purpose of interpretation as “assisting the visitor through a process of discovery that results in personal meaning” and to “impart meaning to present generations and to honor past generations” (p. 74). First, however, one must gain some insight about what is relevant and meaningful to visitors. Hindered by the virtual absence of research on what children think, feel, and do at memorial and other dark sites, we turned to an abundant and readily accessible source of data. As Livingstone et al. (2001) observed, “Although comment cards are commonly collected, they are rarely analyzed for studying museum visitors and the meanings they attach to exhibitions” (p. 358). As others studying ubiquitous visitor comments have noted, we view them as a rich and unique source of data to inform interpretation. Virtually self-generating, this data gathering method does not tax already strained interpretation research budgets (see Ward, 2015, p. 4) and may appeal to academic researchers willing to provide the analyses. We encourage interpreters at a variety of sites, not just those of painful heritage, to consider studying visitor comments (see Kerr, Dugan, & Frese, 2016 for a discussion of practical methods).

Through their comments, we witnessed children making meaning of the horrific deaths commemorated at the Flight 93 National Memorial. Some children gained wisdom and lost innocence, to paraphrase Uzzell (1995). Their comments provided crucial perspectives on “context, holistic awareness, and drawing connections,” which Hunter (2012) called for in interpretation research (p. 56). In the words of the recently retired Flight 93 National Memorial Chief of Interpretation and Cultural Resources, Barbara Black:

You have all given a voice to the words and objects visitors have left—not knowing if anyone would ever see or read them. And especially the expressions of children, who want to be heard as loudly as the adults. (personal communication, July 18, 2016)

We hope this study will inform those daunted by interpreting acts of terrorism. We also hope that our work will encourage others to elicit the views of young visitors, whose voices communicate unique yet often overlooked perspectives.

References

Alderson, P. (2000). Children as researchers: The effects of participation rights on research methodology. In P. Christiansen & A. James (Eds.), Research with children: Perspectives and practices (pp. 241–290). London, England: Routledge.

Alexander, M. (2000). Do visitors get it? A sweatshop museum and visitors’ comments. The Public Historian, 22(3), 85–94.

Beck, L., & Cable, T. T. (2002). Interpretation for the 21st century: Fifteen guiding principles for interpreting nature and culture (2nd ed.). Urbana, IL: Sagamore Publishing.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to research and methods. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Brochu, L., & Merriman, T. (2008). Personal interpretation: Connecting your visitors to heritage resources. Fort Collins, CO: InterpPress.

Brown, E. J., & Goodman, R. F. (2005). Childhood traumatic grief: An exploration of the construct in children bereaved on September 11. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(2), 248–259.

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1-21.

Charmaz, K., & Mitchell, R. G. (2001). Grounded theory in ethnography. In P. Atkinson (Ed.) Handbook of ethnography (pp. 160–174). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Coffee, K. (2006). Museums and the agency of ideology: Three recent examples. Curator, 49(4): 435–48.

Coffee, K. (2011). Disturbing the eternal silence of the gallery: A site of dialogue about hunger in America. Museum Management and Curatorship, 26(1), 11–26.

Dec, M. (2004). Legacy denied. Journal of Interpretation Research, 9(2), 72–76.

Denzin, N. K. (1978). Sociological methods. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Easton, D., & Hess, R. D. (1962). The child’s political world. Midwest Journal of Political Science, 6(3), 229–246.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrade, T.L. (2006). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional and personality development (5th ed. Pp. 701–778). New York: Wiley.

Emde, R. N. (2003). Early narratives: A window into the child’s inner world. In R. Emde, D. P. Wolf, & D. Oppenheim (Eds.), Revealing the inner worlds of young children: The Macarthur story-stem battery and parent-child narratives (pp. 3–26). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Ferguson, M., Piché, J. & Walby, K. (2015). Bridging or fostering social distance? An analysis of penal spectator comments on Canadian penal history museums. Crime Media Culture, 11(3), 357–374.

Frost, W., & Laing, J. H. (2016). Children, families, and heritage. Journal of Heritage Tourism. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2016.1201089

Gordon, A. K., Musher-Eizenman, D. R., Holub, S. C., & Dalrymple, J. (2004). What are children thankful for? An archival analysis of gratitude before and after the attacks of September 11. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(5), 541–553.

Ham, S. (2007). Can interpretation really make a difference? Answers to four questions from cognitive and behavioral psychology. Proceedings, Interpreting World Heritage Conference (pp. 42–52). Fort Collins, CO: National Association for Interpretation.

Ham, S. (2013). Interpretation: Making a difference on purpose. Golden, CO: Fulcrum.

Hornick, B. (2012, Aug. 4). Materials aim to explain Flight 93 to preschoolers. The Tribune Democrat. Retrieved from http://www.tribdem.com/news/local_news/materials-aim-to-explain-flight-to-preschoolers/article_39ea890d-1aa2-5136-a395-ddb458407eed.html

Hunter, J. E. (2012). Towards a cultural analysis: The need for ethnography in interpretation research. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17(2), 47–58.

Kaylor, B. T. (2013). “God bless America” serves to rally Americans to war. Newspaper Research Journal, 34(2), 93–105.

Kerr, M. M., Dugan, S. E., & Frese, K. M. (2016). Using Children’s Artifacts to Avoid Interpretive Missteps. Legacy: The Magazine of the National Association for Interpretation, July/August, 2016.

Kerr, M. M. & Price, R. H. (in press). “I know the plane crashed:” Children’s perspectives in dark tourism. In P. Stone, R. Hartmann, T. Seaton., R. Sharpley, & L. White, L. (Eds.), The Palgrave Macmillian handbook of dark tourism studies. London: Palgrave Macmillian.

Kerr, M. M. & Price, R. H. (2016). Overlooked encounters: Young tourists’ experiences at dark sites. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 11(2), 177–185.

Koc, E., & Boz, H. (2014). Triangulation in tourism research: A bibliometric study of top three tourism journals. Tourism Management Perspectives, 12, 9–14.

Korpela, K. M. (1992). Adolescents’ favourite places and environmental self-regulation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(3), 249–258.

Korpela, K., Kyttä, M., & Hartig, T. (2002). Restorative experience, self-regulation, and children’s place preferences. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(4), 387–398.

Larsen, D. L. (Ed.). (2003). Meaningful interpretation: How to connect hearts and minds to places, objects, and other resources. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service.

Livingstone, P., Pedretti, E., & Soren, B. J. (2001). Visitor comments and the socio-cultural context of science: Public perceptions and the exhibition A Question Of Truth. Museum Management and Curatorship, 19(4), 355–369.

Macdonald, S. (2005). Accessing audiences: Visiting visitor books. Museum and Society, 3(3), 119–136.

Machlis, G., & Field, D. (1992). Getting connected: An approach to children’s interpretation. In G. Machlis and D. Field (Eds.). On interpretation: Sociology for interpreters of natural and cultural history, (pp. 65–74). Corvallis: OR: Oregon State University Press.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, M. A., & Saldaña, J. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miles, S. (2014). Battlefield sites as dark tourism attractions: An analysis of experience. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(2), 134–147.

Morris, B. J. (2011). The frightening invitation of a guestbook. Curator: The Museum Journal, 54(3), 243–252.

Munar, A. M., & Ooi, C. S. (2012). The truth of the crowds: Social media and destination management. In L. Smith, E. Waterton, & S. Watson (Eds.), The cultural moment in tourism (pp. 255–273). London, England: Routledge.

Patton, M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. HSR: Health Services Research, 34(5), 1189–1208.

Pekarik, A. J. (1997). Understanding visitor comments: The case of Flight Time Barbie. Curator: The Museum Journal, 40(1), 56–68.

Phillips, D., Prince, S., & Schiebelhut, L. (2004). Elementary school children’s responses 3 months after the September 11 terrorist attacks: A study in Washington, DC. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(4), 509–528.

Pinter, A. (2014). Child participant roles in applied linguistics research. Applied Linguistics, 35(2), 168–183.

Pinter, A., & Zandian, S. (2014). “I don’t ever want to leave this room”: Benefits of researching ‘with’ children. ELT Journal, 68(1), 64–74.

Pinter, A., & Zandian, S. (2015) “I thought it would be tiny little one phrase that we said, in a huge big pile of papers”: Children’s reflections on their involvement in participatory research. Qualitative Research, 15(2) , 235–250.

Poria, Y., & Timothy, D. J. (2014). Where are the children in tourism research? Annals of Tourism Research, 47, 93–95.

Price, R. H., & Kerr, M. M. (2017). Child’s play at war memorials: Insights from a social media debate. Journal of Heritage Tourism. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/1743873X.2016.1277732

Reid, S. E. (2005). In the name of the people: The Manège affair revisited. Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, 6(4), 673–716.

Rosenblum, G. D., & Lewis, M. (2006). Emotional development in adolescence. In G. R. Adams & M. D. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 24–47). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Saltzman, W. R., Pynoos, R. S., Lester, P., Layne, C. M., & Beardslee, W. R. (2013). Enhancing family resilience through family narrative co-construction. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(3), 294–310.

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 24(3), 230–240.

Small, J. (2008). The absence of childhood in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(3), 772–789.

Sobel, D. (1993). Children’s special places. Tucson, AZ: Zephyr Press.

Stone, P. R. (2012). Dark tourism as ‘mortality capital’: The case of Ground Zero and the significant other dead. In R. Sharpley & P. R. Stone (Eds.), Contemporary tourist experience: Concepts and consequences (pp. 71–94). Abington, England: Routledge.

Sutcliffe, K., & Kim, S. (2014). Understanding children’s engagement with interpretation at a cultural heritage museum. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(4), 332–348.

Tilden, F. (2009). Interpreting our heritage. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Uzzell, D. L. (1995, November) The getting of wisdom or the losing of innocence: Interpretation comes of age. Keynote address presented at the Fourth Annual Conference of the Interpretation Australia Conference, Canberra, AU.

Uzzell, D. L. (1998). Interpreting our heritage: A theoretical interpretation. In D. L. Uzzell and R. Ballantyne (Eds.), Contemporary issues in heritage and environmental interpretation: Problems and prospects (pp. 11–25). London, England: The Stationery Office.

Veal, A. J. (2006). Research methods for leisure and tourism: A practical guide. Essex, England: Pearson Education.

Ward, C. (2015). Note from the editor. Journal of Interpretation Research, 20(2), 3–4.