Journal of Interpretation Research

Volume 22, Number 2

An Investigation into the Impact of Environmental Education Certification on Perceptions of Personal Teaching Efficacy

Mandy Harrison, Ph.D.

Department of Recreation Management and Physical Education

Appalachian State University

Holmes Convocation Center, 111 Rivers Street

Boone NC, 28608

harrisonmb@appstate.edu

Lisa Gross, Ph.D.

Department of Curriculum and Instruction

Appalachian State University

Jennifer McGee, Ph.D.

Department of Curriculum and Instruction

Appalachian State University

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine how participation in the North Carolina Environmental Educator (NCEE) program influences the individual’s perceived self-efficacy. Specifically, this study examines the impact of NCEE certification on participants’ perceived personal teaching self-efficacy. This study compared personal teaching efficacy scores of certified environmental educators, non-certified environmental educators, and licensed schoolteachers. The study found significant differences in teaching efficacy between certified and non-certified environmental educators, as well as certified environmental educators and licensed school teachers. In addition, the study found no significant difference in efficacy scores between NCEE certified licensed school teachers and NCEE certified environmental educators.

Results of this study indicate a link between environmental education certification and higher personal teaching efficacy.

Keywords

certification, teaching self-efficacy, formal and non-formal educators

Introduction

For over a century, environmental education (EE) programs have contributed to society’s understanding of the relationship between the environment and human health and welfare. In the past 50 years, the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, followed by numerous actions at the federal and state level, has resulted in formal and non-formal programs that promote EE as a means of improving upon current conditions.

In the United States, each state varies in its approach and methods of training for environmental educators; to achieve competency for certification, all programs are rigorous and comprehensive (Glenn, 2004). North Carolina began offering EE certification in 1997, a process that has evolved into a formalized training program facilitated through the Department of Environmental Quality. More recently, the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) has begun accreditation of state EE certifying programs. Fourteen states currently offer environmental education certification, though only three are NAAEE accredited. While much qualitative feedback and internal program analyses indicate success in achieving the goals of formalized environmental educator preparation (NAAEE, 2016), little research has been conducted on the certification training.

In North Carolina, interested individuals can attend a number of workshops or programs whether seeking certification or not. The North Carolina Environmental Educator (NCEE) certification program requires the fulfillment of particular criteria and includes standards for professional excellence for formal and non-formal educators. The purpose of this study is to examine how participation in the NCEE program influences the individual’s perceived self-efficacy. Specifically, this study examines the impact of NCEE certification on participant’s perceived personal teaching self-efficacy.

Description of NCEE Program

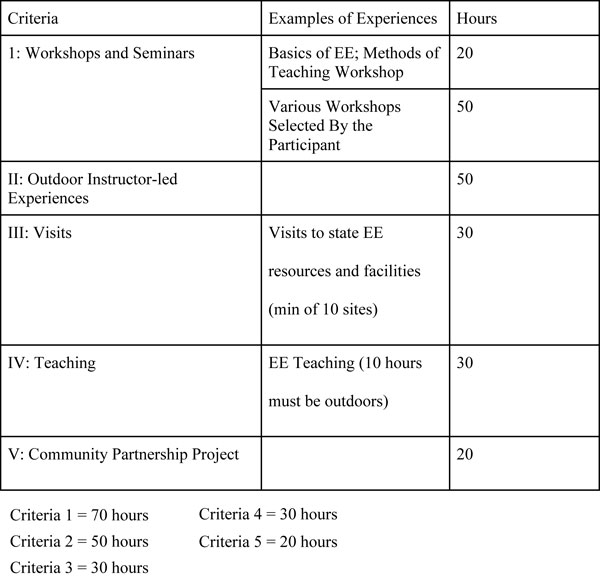

To become a certified NC environmental educator, participants complete 200 hours of training that have been organized across five criteria (Table 1). Seventy of the required hours fall under “Criteria I: Workshops and Seminars.” Within this criterion, two seminars are required for all participants: “Basics of Environmental Education” and “Methods of Teaching Environmental Education.” Both courses total 20 hours and provide the environmental educator with pedagogical approaches and background for teaching environmental education. The remaining 50 hours include workshops selected by the participant that focus on national and/or state curriculum. Project Wild, Project Learning Tree, Flying Wild, CATCH, the Leopold Education Project, and Sea Turtle Exploration are a few examples. These seminars are offered by a variety of state parks, the NC Wildlife Resources Commission, and environmental education centers.

Criteria II require that the participant engage in 50 hours of “Outdoor Instructor-led Experiences.” The State certifying agency recommends university or college courses “such as ecology, forestry, etc., which include an outdoor lab, instructional workshops or field trips held in an outdoor environment, or organized nature hikes led by environmental education professionals at parks, forests, zoos, aquariums and other Environmental Education Centers” (North Carolina Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs, 2016).

Criteria III, IV, and V total 80 hours, 30 of which include visits to state EE resources and facilities (with a minimum of 10 different sites); 30 dedicated to environmental education teaching (with a minimum of 10 hours conducted outdoors) and the remaining 20 hours centered on a “Community Partnership Project”. To meet this final criterion, participants must “lead a partnership that will have a positive and lasting effect on the community and that will increase environmental awareness and understanding” (http://www.eenorthcarolina.org/certification--about-the-program.html).

Table 1. NCEE Requirements

Table 1. NCEE Requirements

Literature Review

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy stems from social cognitive theory, a theory that describes human behavior in terms of the aptitude to interpret one’s environment and reflect upon, evaluate, and influence one’s self. In this manner, humans are in fact agents of the path one’s life takes. While talent, skill, and physical and psychological environment influence direction, achievement, and health, it is the individual’s belief regarding his or her effectiveness that mediates the influence of the aforementioned factors (Bandura, 1977). This belief is referred to as perceived self-efficacy. Using self-efficacy as a general outcome measure of the effectiveness of a program or intervention (such as the concept of self-esteem has been used) is not appropriate. However, self-efficacy measures can be predictive of behavior when targeted and specific, such as personal teaching efficacy in regard to teaching environmental education content.

Perceptions of self-efficacy originate from the interaction of four sources of information (Bandura, 1997):

1. Mastery experiences (performance accomplishments) that indicate to an individual how capable he or she is;

2. Vicarious experiences (observing others) through which an individual can learn, or through social comparison, draw conclusions regarding his or her capability;

3. Verbal persuasion that serves to influence an individual regarding his or her capabilities, and

4. Physiological and affective states (such as physical manifestations of nervousness) that individuals regard as indications of capability.

By addressing and assessing such sources of efficacy information, one can provide experiences that are more likely to change an individual’s efficacy perceptions.

Self-efficacy is not to be confused with “overall” sense of self. Self-efficacy is the perception of one’s ability to perform a specific behavior (Bandura, 1997). Research conducted on individuals who participate in a wide variety of activities shows that, controlling for ability, self-efficacy regarding a specific task remains a significant contributor to performance (Cervone, 1989; Bandura, Reese, & Adams, 1982; Bandura, 1997; Finney & Schraw, 2003; Oliver & Cronan, 2002; Wise, 2002). While there is some evidence of the causal nature of perceived efficacy, it does not necessarily cause success, but rather mediates willingness to learn, enact, and maintain a behavior (Bandura, 1997).

Teacher self-efficacy

As non-formal educators, participants in environmental education programs develop self-efficacy over time and through ongoing interactions with their participants. Teacher self-efficacy has been defined many ways in the literature. Berman et al. (1977) define teaching efficacy as “the extent to which the teacher believes he or she has the capacity to affect student performance” (p. 137). Woolfolk and Hoy (1990) describe it as the teacher’s belief that he or she can influence student learning. Guskey and Passaro (1994) explain how teaching efficacy includes the “teachers’ belief or conviction that they can influence how well students learn, even those who may be difficult or unmotivated” (p. 4). The slight variation in these definitions often contradict each other and can ultimately lead to confusion within the field about how to accurately measure the construct (Pajares, 1997; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001). Regardless, one’s sense of efficacy regarding his or her ability to teach has been related to student outcomes (Ross, 1992; Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989; Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2000; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001; Leithwood & Jantzi, 2008). Therefore, the individual with a higher perceived self-efficacy regarding his teaching ability is more likely to have higher achieving and more motivated students (Bandura, 1997).

Teacher self-efficacy measures. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (1977) consists of two main constructs: efficacy expectations and outcome expectations. Efficacy expectations are an individual’s convictions for orchestrating the necessary actions to complete a task. Outcome expectations are defined as an individual’s expectations for performing a task that will lead to a certain outcome. Gibson and Dembo (1984) elaborated upon Bandura’s idea of outcome expectations and efficacy expectations and attempted to measure the two constructs using general teaching efficacy (GTE) (representing outcome expectations) and personal teaching efficacy (PTE) (representing efficacy expectations) (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001; Woolfolk & Hoy, 1990). GTE and PTE are the two constructs measured in the Teacher Efficacy Scale (TES) (Gibson & Dembo, 1984). Other researchers used the Gibson and Dembo’s TES as a springboard to measure self-efficacy within specific contexts by rewording the TES items to be content-specific.

The Science Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument (STEBI) constructed by Riggs and Enochs (1990) is one such measure. For the STEBI, PTE was left as is while GTE became Science Teaching Outcome Expectancy (STOE). Enochs and Riggs (1990) published two versions of the STEBI, version A (Riggs & Enochs, 1990) and version B (Enochs & Riggs, 1990). Version A was written for in-service elementary teachers while version B was written for pre-service elementary teachers. In this study, we use the STEBI-B for two reasons: like pre-service teaching candidates, the majority of individuals participating in the EE certification program have limited to no formal teaching training. Second, the comparative group includes elementary pre-service teachers who have participated in at least one EE workshop. Both groups are engaged in a component of the EE certification process, but have limited formal teaching experiences.

Efficacy and Environmental Educators

The majority of participants enrolling in the NCEE certification program are either formal or non-formal educators. To distinguish between the two, formal educators are typically K–12 classroom teachers, including both pre-service and in-service practitioners. Non-formal educators include but are not limited to rangers, environmental educators, docents, and park volunteers. In North Carolina, there are cases in which EE certification must be obtained for a state position (e.g., park ranger) and there are cases in which EE certification is not recognized as a licensure area (e.g., school teacher). Therefore, if not mandated, the majority of participants who seek certification do so out of interest or for professional development purposes.

A number of efficacy studies have been conducted on formal educators’ science teaching and learning as situated within or through an environmental education program. Carrier (2009) examined a group of pre-service candidates (PCs) teaching elementary-age children environmental science lessons (in the outdoors) as part of her science methods course. EE lessons were taught at a forest ecology preserve with school groups using Project WILD lessons. The researcher noted an increased comfort in PCs’ teaching, suggesting the field experience as important to efficacy development. Mosely, Reinke, and Bookout (2002) evaluated how PCs participation in a three-day outdoor environmental education program influenced attitudes toward self-efficacy. Unlike Carrier’s outcomes, Mosely et al. reported little change from the experience, indicating a significant drop in efficacy over time. There was no significant change in outcome expectancy as a result of participation in the program. In another study, researchers measured the efficacy beliefs of biology teachers in environmental education using Sia’s (1992) “Environmental Education Self-Efficacy Belief Scale” (Cimen, Gökmen, Altunsoy, Ekici, & Yilmaz, 2011). They investigated differences in gender, years of training, and professional membership related to efficacy beliefs. While no significant difference between gender, teachers who were involved in professional organizations had significantly higher efficacy than those who were not involved. Additionally, years of training were correlated with higher efficacy scores.

There are few studies related to EE efficacy beliefs of non-formal educators. However, in a 2008 a study investigating the effects of EE training with non-formal educators, researchers found significant differences after an EE training between pre- and post-test specific EE content efficacy, motivation efficacy, and a combination of the two, termed total teaching efficacy of whitewater raft guides. All three comparisons were found to be significant (p < .005), indicating an increase in self-efficacy as a result of the seminar training. The researchers found that age, gender, position, or length of time in the field were not significant predictors of total teaching efficacy or motivation efficacy (Harrison & Banks, 2008). In a follow-up study, the experiences of raft clients who were in the boat of a guide who had participated in the previously mentioned EE training was compared to those whose guide had not participated in the EE training. The study found that overall scores were statistically significantly higher (p < .005) for both interest and knowledge regarding the river environment for all clients following their river rafting experience. Post scores for clients whose guide attended the EE training were statistically significantly higher (p < .005) for both interest and knowledge over the clients whose guide did not attend (Author, 2010).

The NCEE certification is structured in many ways to address the sources of information from which an individual draws to make efficacy judgments. For example, the certification requirements for practice teaching and community partnership (mastery experience), observing peers and professionals teaching (vicarious experience), and in many cases, receiving verbal feedback from facilitators as well as peers (verbal persuasion) contribute to a process which is gradual and builds on successes, creating opportunity for the mastery experience. In order to better understand the influence of certification on perceived self-efficacy with regard to EE facilitation, the following research questions were investigated:

1. Is there a difference in self-efficacy perceptions between those who had completed certification and those who were earning certification at the time of the survey?

2. Is there a difference in PTE between EEs and licensed classroom teachers?

3. Does certification along with career predict PTE?

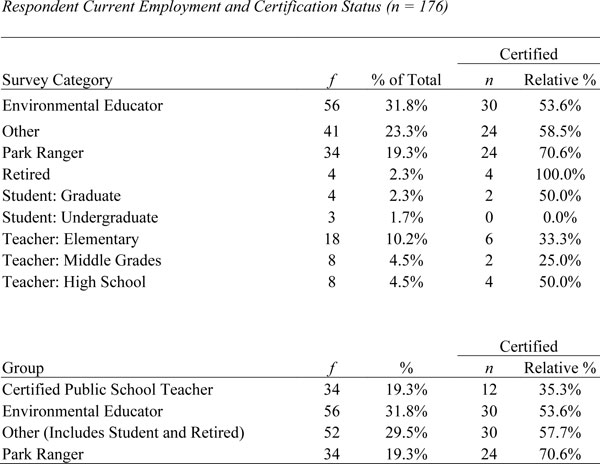

Table 2

Table 2

Methods

This study utilized survey research methodology. The survey had 48 items and was organized into four sections. Respondents completed the survey online using Survey Monkey™. The survey was available for 30 days. Two validated instruments were included in the survey along with a section concerning demographics and a section concerning challenges and beliefs regarding EE. The two validated instruments were the STEBI-B (Science Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument version B) and the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP). Both are detailed below, although only the STEBI-B was used for this study.

Participants

The participants in this study were drawn from two sources. The first source was the NC-EE listserv. This listserv was accessed with the cooperation of the N.C. Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs.

The second source, the comparison group, was an alumni database of elementary education graduates from a college of education at a midsize public university in North Carolina. This comparison group was chosen as a convenience sample, and additionally because these teaching candidates had been required to attend at least one EE workshop as a part of a science teaching methods course during their tenure in the elementary education program. Their familiarity with and participation in a workshop as well as their potential to continue in the EE certification program provide us with an opportunity to examine self-efficacy in terms of those with formal pedagogical training and those without. Using the college database, elementary education majors (n=973) who graduated between spring 2010 and spring 2015 were invited to participate.

All individuals were sent an email describing the study, with a link to an online survey. While participants from both sources were personally invited to participate in the study, responses to the survey were anonymous and data self-reported. Therefore survey responses could not be connected to the original database information. The survey was sent to approximately 800 individuals. Two hundred twenty-seven participants completed the survey (28% response rate). Some of the participants who responded to the online survey did not complete all items, thus incomplete surveys were not included in analysis. The final number of complete surveys was 176. These participants were grouped into four categories based on identified role/position: 38 (18.63%) identified as NC State Park Rangers, 66 (32.35%) as environmental educators, and 44 (21.57%) as licensed public school teachers (elementary, middle, and high school). (For further breakdown of each category see Table 2.) Of the participants, 77 (37.7%) were currently seeking NCEE certification. Ninety-seven (47.5%) of the respondents were already certified. Within the certified group, 21 percent were male and 79 percent female.

Survey Instrument

The online survey contained four sections. Section I included general and demographic items, as well as questions pertaining to challenges and perspectives regarding environmental education. Only the demographic questions in this section were utilized in this study. Section II of the survey included a modified STEBI Version B (Enochs & Riggs, 1990). The STEBI-B was created for use with preservice teachers. As an attitudinal measure, the limited pedagogical experiences of the two participant groups were better measured with this instrument than STEBI-A, which was created for in-service teachers. A sample item from the STEBI-B that measures the construct of PTE reads, “When a student does better than usual in science, it is often because the teacher exerted a little extra effort.” The respondent answers this item on a Likert-type scale ranging from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” For the purpose of this study, items were reworded to include environmental education and the EE role. For example, the item above was reworded to read, “When a student does better than usual in science or environmental education, it is often because the teacher/facilitator exerted a little extra effort.” Both constructs on the STEBI-B (Science Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument) were included on the survey but for the purpose of this study we only analyzed PTE. Section III included items specific to NCEE certification. Participants were asked to state their certification status as well as the number of seminars they had completed. Participants were also asked to detail the number of hours they had completed towards the five different NCEE criteria. Participants usually completed this section only if they had not completed the certification.

Data Analysis

The data were cleaned and recoded in order to investigate the research questions. After deleting cases with an extreme amount of missing data, removing duplicate responses, and removing participants who did not complete the STEBI-B (Science Teaching Efficacy Belief Instrument), 176 participants remained in the dataset (see Table 1). Some of the items (3, 6, 8, 17, 19, 20, and 22) were reverse coded (Enochs & Riggs, 1990) and those items were treated as such in the dataset.

Next, the two constructs measured on the STEBI-B were analyzed. Those two constructs are PTE (Personal Teaching Efficacy) and STOE (Science Teaching Outcome Expectancy). Means for both PTE and STOE were computed for each participant. If the participant skipped an item, imputation of the mean for that construct was conducted using the mean for that construct. As PTE is the focus of this study, reliability of the PTE construct was examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = .62). The Cronbach’s alpha is a bit lower than is ideal but the researchers hypothesize that is due to the difference in time after certification, meaning that some participants had likely completed the certification process recently while others had completed it years prior. Unfortunately years of experience were not included in the survey data. For all tests of significance the alpha was set at α = .05, a priori.

Results

A t-test was used to investigate the first research question: is there a difference in self-efficacy perceptions between those who had completed certification and those who were earning certification at the time of the survey.

Having examined the surveys from the 176 participants, 96 (54.5%) of the participants were NCEE certified and 80 were completing certification at the time of the survey. Six participants did not answer the question about certification. Those who had earned certification had a mean score of 3.88 (SD = .36, n = 96) for PTE and those in the process of earning certification had a mean score of 3.74 (SD = .36, n = 80). The t-test revealed a statistically significant difference between groups with regard to PTE (p = .01). The effect size between groups was medium (d = .39).

An ANOVA was used to investigate the second research question: Ts there a difference in PTE between EEs and licensed classroom teachers?

Traditional EEs for this analysis included both participants who identified as “environmental educators” and “park rangers” who were either NCEE certified or were in the process of obtaining NCEE certification. The ANOVA indicated a statistically significant difference between these two groups with regard to PTE. The EE group had a higher mean PTE score (n = 90; M = 3.82, SD = .32) than the licensed public school teachers (n = 34; M = 3.69, SD = .42). This result was statistically significant (p = .04). The effect size for this analysis was medium (d = .37).

To further test this hypothesis, we examined only certified EEs and the small number of teachers in the comparison group that were EE certified. This greatly reduced the sample size for the analysis (EE, n = 54; teachers, n = 12). The difference in PTE was not statistically significant although sample size likely played a role.

In order to further investigate PTE, the PTE of certified EEs and (non–EE certified) licensed teachers was then examined. The certified EEs (n = 54, M = 3.80, SD = .37) had a statistically significantly higher PTE than the non-certified licensed teachers (n = 22, M = 3.60, SD = .44) (p = .005). This validated our hypothesis that certified EEs had a higher PTE than the comparison group (non-certified licensed teachers).

As certification does seem to have an impact on PTE, the focus of research question 3 was to examine whether NCEE certification coupled with the respondent’s occupation could predict PTE. In order to conduct this analysis, participants were first grouped into larger job categories based on their responses to the survey. These groupings can be seen in Table 2. Although the group sizes were not entirely equal, an examination of the data showed normality that allowed us to proceed with the analysis.

A hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to determine whether NCEE certification and career (licensed public school teacher, environmental educator, park ranger, and other) could predict on PTE. The results of step one indicated that the variance accounted for (R2) with the first predictor (NCEE certification) equaled .035 (adjusted R2 = .029), which was significantly different from zero (F(1, 174) = 6.24, p < .01). Next, career was entered into the regression equation. The change in variance accounted for (DR2) was equal to .01, which was not a statistically significant increase in variance accounted for over the step one model.

Discussion

Overall, our findings indicate that NCEE certification may indeed be linked to higher personal teaching efficacy (PTE). Participants in this study who were EE certified had a higher mean PTE score than those who were in the process of certification, and that difference was statistically significant. Additionally, the environmental educators—whether EE certified or in the process of certification—and the comparison group (licensed public school teachers) were examined with regard to PTE. Environmental educators had a higher PTE than the comparison group and that difference was statistically significant. Then, the PTE of only the certified environmental educators was compared to that of non-EE certified licensed public school teachers and the difference was statistically significant. Certified environmental educators had a higher mean PTE. Additionally, further examination of certified environmental educators and EE certified teachers did not yield statistically significant differences with regard to PTE score.

Another research question for this study concerned the ability of the certification process, coupled with the participants’ career, to predict PTE. After dividing the participants into four very different career groupings (environmental educators, licensed public school teachers, park rangers, and other), we examined the predictive ability of the PTE. Our hypothesis was that certification would play a role in self-efficacy but that this might be mediated or enhanced by the participant’s career. For example, we hypothesized that the public school teacher group might have a higher PTE than the “other” group, simply based on occupational trajectory. Our hypothesis was partially proven to be true as certification predicted a very small percentage (3.5%) of variance in PTE, although it was statistically significant (p < .01). Occupation however, did not account for any variance in PTE. This finding in particular provides evidence that completing the NCEE certification process does enhance PTE.

The evidence provided here shows that the overall certification process has positive benefits for participants, which previous literature (Ross, 1992; Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989; Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2000; Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2001; Leithwood & Jantzi, 2008) indicates creates, in turn, positive benefits for the NCEE certified educators’ students and participants.

However, there are several limitations of this study, which should be noted. One such limitation of this study is the design itself. As this was survey research and not a controlled pre and post evaluation of the training programs, we can only make educated assumptions about how the training program impacted PTE. Obtaining certification, however, does maintain its importance with level of PTE through our analysis of the data. Additionally, having participants from so many different occupations gave us heterogeneous groups of participants. Even through our best efforts to maintain consistency, it was difficult to treat all environmental educators and all teachers the same, for example. Some of the teachers (comparison group) did actually obtain certification, making it hard to use them as a consistent comparison to certified environmental educators. Also, some environmental educators had not completed their certification at the time of this study, therefore our results might look more substantial had the survey been given to all EEs at the end of their certification and within the same time period.

The major limitation of this study is temporality. These results do not take into account time between starting the certification and completing the certification, or similarly, pre- and post-certification efficacy measures. The results do not take into account the amount of time an individual spends facilitating EE, or how long he or she has been an environmental educator. Acknowledging this, we cannot suggest a causal relationship between certification and PTE. However, given the multiple results of this study that point to a link between NCEE certification and higher PTE, we feel confident in suggesting that environmental education training is worthwhile for those who are or would be environmental educators, and likely for those in more traditional, formal education settings as well. One reason for this may be because the certification process is structured to provide participants with opportunities to observe peers, receive feedback from professionals, and to have mastery experiences, all sources of information that can affect efficacy perceptions (Bandura, 1997). Essentially, the EE certification process includes essential experiences that increase knowledge as well as efficacy, thus increasing the likelihood of successful teaching and facilitation experiences. These successful “mastery” experiences in turn bolster a facilitator’s efficacy, which again can affect performance in positive ways. The results of this study indicate the possibility that certified environmental educators might be more effective in increasing society’s understanding of the relationship between the environment and human health and welfare—confirming this is an appropriate focus for future research. Finally, the results of this study indicate that, as EE certifications become more common, EE organizations might consider requiring or preferring EE-certified job candidates and employees.

References

Acury, T.A., Johnson, T. P., & Scollay, S. (1986). Ecological worldview and environmental knowledge. The ‘new environmental paradigm.’ Journal of Environmental Education, 17(4), 35–40.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Bandura, A., Reese, L., & Adams, N.E. (1982). Microanalysis of action and fear arousal as a function of differential levels of perceived self-efficacy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 5–21.

Berman, P., McLaughlin, M., Bass, G., Pauly, E., & Zellman, G. (1977). Federal programs supporting educational change. Vol. VII Factors affecting implementation and continuation (Report No. R-1589/7-HEW) Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corporation (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 140 432).

Carrier, S.J. (2009). The effects of outdoor science lessons with elementary school students on preservice teachers’ self-efficacy. Journal of Elementary Science Education, 21(2), 35–48.

Cervone, D. (1989). Effects of envisioning future activities on self-efficacy judgments and motivation: An availability heuristic interpretation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 13, 247–261.

Cimen, O., Gökmen, A., Altunsoy, S., Ekici, G., & Yilmaz, M. (2011). Analysis of biology candidate teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs on environmental education. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2549–2553.

Enochs, L., & Riggs, I. (1990). Further development of an elementary science teaching efficacy belief instrument: A preservice elementary scale. School Science and Mathematics, 90, 694–706.

Ewert, A., Place, G., & Sibthorp, J. (2005). Early-Life Outdoor Experiences and an Individual’s Environmental Attitudes. Leisure Sciences, 27: 225–239.

Finney, S. J., & Schraw, G. J. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs in college statistics courses.Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28, 161–186.

Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 569–582.

Glenn, S. S. (2004). Individual behavior, culture and social change. The Behavior Analyst, 27(2), 133–151.

Goddard, R.D., Hoy, W.K., & Hoy, A.W. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: its meaning, measure and impact on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 479–507.

Guskey, T. R., & Passaro, P. D. (1994). Teacher efficacy: A study of construct dimensions. American Educational Research Journal, 32, 627–643.

Harrison, M., & Banks S. (2008). An evaluation of a Headwaters Institute watershed seminar. Journal of Interpretation Research, 13(2), 83–87.

Harrison, M., Banks S., & James, J. (2010). An evaluation of the impact of river guide interpretation training on the client’s knowledge and interest regarding the environment. Journal of Interpretation Research, 15(1), 39–43.

Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2008). Linking leadership to student learning: The role of collective efficacy. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 496–528.

Midgley, C. M., Feldlauger, H., & Eccles, J. (1989). Changes in teacher efficacy and student self- and task-related beliefs during the transition to junior high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 247–58.

Moseley, C., Reinke, K., & Bookout, V. (2002). The effect of teaching outdoor environmental education on preservice teachers’ attitudes toward self-efficacy and outcome expectancy. Journal of Environmental Education, 34(1), 9–15.

North American Association of Environmental Education. (2016, July.) Retrieved from: About EE Certification. https://naaee.org/eepro/resources/about-ee-certification

North Carolina Office of Environmental Education and Public Affairs. (2016). Retrieved from: North Carolina Environmental Education certification program: http://www.eenorthcarolina.org/certification--about-the-program.html

Oliver, K., & Cronan, T. (2002). Predictors of exercise behaviors among fibromyalgia patients. Preventive Medicine, 35(4), 383–389.

Pajares, F. (1997). Current directions in self-efficacy research. In M. Maehr & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.). Advances in motivation and achievement. Volume 10, pp. 1–49.Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Riggs, I., & Enochs, L. (1990). Towards the development of an elementary teacher’s science teaching efficacy belief instrument. Science Education, 74, 625–637.

Ross, J. A. (1992). Teacher efficacy and the effect of coaching on student achievement.Canadian Journal of Education, 17(1), 51–65.

Sia, A. R. (1992). Preservice elementary teachers perceived efficacy in teaching environmental education: a preliminary study. Paper presented at the ECO-E0 North American Association for Environmental Education Conference, Toronto, Canada, October 20, 1992.

Stedman, R. C. (2002). Toward a social psychology for place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude and identity. Environment and Behavior, 34, 561–581.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783–805.

Wise, J. (2002). Social cognitive theory: A framework for therapeutic practice.Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 36, 335–351.

Woolfolk, A. E., & Hoy, W. K. (1990). Prospective teachers’ sense of efficacy and beliefs about control. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 81–91.