Journal of Interpretation Research

Volume 22, Number 2

Interpretation Training Needs in the 21st Century: A Needs Assessment of Interpreters in the National Park Service

Robert B. Powell

George B. Hartzog, Jr., Endowed Professor

Director, Institute for Parks

Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management

and Department of Forestry and Environmental Conservation

128 McGinty Court

281 Lehotsky Hall

Clemson University

Clemson, SC 29634-0735

864.656.0787

rbp@clemson.edu

Gina L. Depper

Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism Management

Clemson University

Clemson, SC 29634-0735

gdepper@clemson.edu

Brett A. Wright

Dean, College of Behavioral, Social, and Health Sciences

Clemson University

Clemson, SC 29634-0735

wright@clemson.edu

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank former National Park Service Associate Director of Interpretation, Education, and Volunteers Julia Washburn, Stephen T. Mather Training Center, interpretation and education specialists Katie Bliss, John Rudy, Kimble Talley, and Becky Lacome, the NPS National Advisory Board Education Committee, and the many interpretation and education subject matter experts that invested their time and expertise in this project.

Abstract

To identify critical training needs in the Interpretation and Education (I&E) Division within the National Park Service (NPS), a team of experts and practitioners, including six academic institutions, the National Association for Interpretation, and the NPS, developed a comprehensive list of knowledge, skills, and abilities thought to be relevant for providing and managing interpretation in the 21st century. Using this list of 80 competencies, we received over 1,000 NPS I&E employees’ responses regarding their beliefs about the importance and their level of preparation performing these tasks. The results identified not only the most important competencies, but also three broad training needs: skills related to research-evaluation literacy, engaging new and diverse audiences, and using emerging and existing social media technologies. Preparing interpreters to perform these skills at the highest level appears imperative if the NPS is to maintain relevance and continue to meet the demands of 21st-century audiences.

Keywords

interpretation, competencies, and evaluation

Introduction

As the largest provider of interpretation in the U.S., the National Park Service (NPS) has contributed significantly to the profession for over a century by sponsoring research, in-service training, and developing certification standards. Entering its second century, the NPS seeks to continue to provide enjoyable, relevant, and educational experiences for the changing U.S. population (NPS, 2014). However, advances in technology, changes in culture, and other economic and social forces are changing visitors’ expectations, desires, and preferences (Council on Environmental Quality, 2011; McCown, Laven, Manning, & Mitchell, 2012; National Parks Second Century Commission, 2009). In light of these social changes, the NPS Interpretation and Education (I&E) made a commitment to review interpretive approaches and techniques to align with the needs of contemporary visitors.

This is the second “needs assessment” focused on I&E undertaken by the NPS, the first of which occurred in 1995 (Wright & Makay, 1995). Because much has changed since 1995, subject matter experts (SMEs) reviewed and updated the competencies needed to perform at the highest level. From these competencies, we developed an online survey that asked NPS employees who have responsibilities in I&E to evaluate the importance of and their level of preparation to perform tasks and responsibilities essential to providing and managing interpretation services in the 21st century. This process allowed us to identify gaps in preparation for performing important I&E tasks that ultimately informed future training efforts.

Study Purpose

The overarching purpose of this research was to identify the training needs of NPS personnel that have I&E responsibilities. To accomplish this purpose, we took the following steps: a) reviewed and revised the I&E competencies performed within the NPS; b) assessed the importance of these competencies to job performance; c) assessed the level of preparedness of employees to perform these competencies; d) determined the gaps existing between the importance assigned to, and perceived preparation to perform, each competency which identified the training needs of the NPS I&E workforce; and e) examined if there are different training needs depending upon the age of individuals.

Methods

Following the procedures outlined by Hammitt, Machnik, Rodgers, and Wright (2007), Machnik, Hammitt, Rodgers, and Wright (2007), Weddell, Fedorchak, and Wright (2009, 2013), and Depper, Vigil, Powell, and Wright (2016), we undertook a multi-stage process that included a series of participatory workshops with SMEs to develop and refine a list of competencies. We then developed a survey with these items and surveyed all NPS employees with I&E responsibilities.

Competency Development

To begin the process of developing competencies, also known as knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs), we reviewed the current and emerging goals pertaining to the NPS I&E program. We also reviewed the goals of organizations that shared similar missions. Using this comprehensive review we developed a draft list of potential outcomes for I&E for the 21st century. This process coincided with a parallel effort that generated the NPS Service-wide Interdisciplinary Strategic Plan for Interpretation, Education, and Volunteers (National Park Service, 2014) and the vision paper, Interpretive Skills: 21st Century National Park Service (National Park System Advisory Board Education Committee, 2014), which further defined the outcomes for I&E in the 21st century. Next, we began a systematic process of identifying in the peer reviewed literature, “best practices” that were thought to achieve and enhance these desired visitor outcomes. This literature review included over 70 articles pertaining to interpretation (Skibins, Powell, & Stern, 2012), approximately 66 articles pertaining to environmental education (Stern, Powell, & Hill, 2014), and over 119 articles on interpreting climate change and other controversial and complex issues (Brownlee, Powell, & Hallo, 2012).

In addition, we utilized the findings from a large NPS service-wide research project that identified which programmatic elements and practices lead to better outcomes in live interpretation. This study investigated 376 live interpretive programs and monitored over 56 programmatic characteristics to establish their link with desired visitor outcomes (Powell & Stern, 2013a, 2013b; Stern & Powell, 2013; Stern et al., 2013). These efforts informed the preliminary development of skills and competencies needed to effectively provide interpretation and education services.

In September 2013, I&E subject matter experts, the Interpretation and Education Learning and Development Advisory Committee (which includes academics and members from professional interpretive organizations, along with NPS field practitioners, peer review certifiers, and the regional lead coaching team), and training specialists from Stephen T. Mather Training Center met to examine the list of outcomes and “best practices” produced from this review. The goal of the process was to revise and update the list of competencies that would be relevant in the 21st century and were deemed necessary to perform at high levels within NPS I&E. This group of professional experts ultimately identified six major categories of competencies and developed their operational definitions.

Instrument Development

Using the list of competencies, the authors, in collaboration with the I&E training team, developed a draft online survey. We then pilot tested the survey using NPS I&E professionals. We adjusted the wording of the competencies and made other minor modifications to the survey based on an iterative process of pilot testing, feedback, and peer review with the I&E training team and SMEs. The final instrument included 80 items (specific competencies) nested under six broad categories: Audience Experience (16 items), Finding and Assessing Knowledge (12 items), Appropriate Techniques (19 items), Partnering, Collaboration, and Community Outreach (8 items, 4 of which were asked only of supervisors), Planning and Evaluation (11 items, 4 of which were asked only of supervisors), and Professional Development of Self and Others (15 items, 3 of which were asked only of supervisors). Respondents were asked to rate each of the items twice using a 7-point likert scale; first for importance (1=unimportant to 7=extremely important) and next for their level of preparedness (1=unprepared to 7=extremely well prepared).

Sample and Data Collection

The Associate Director for Interpretation, Education, and Volunteers sent an email invitation to all 3,469 NPS employees designated as having I&E responsibilities on March 19, 2014. These I&E employees were asked to complete the online survey as part of their normal duty. Three follow-up e-mail reminders were sent to all I&E employees on March 31, 2014, April 14, 2014, and April 21, 2014, following recommendations by Dillman, Smyth, and Christian (2009). Data collection ceased on April 28, 2014. By design, most seasonal employees were excluded due to the timing of the study, which is a limitation of the study. Seasonal employees and volunteers provide the majority of live interpretation for the NPS.

Data Analyses

The mean importance assigned to each competency, the mean preparation to perform each competency, and the mean weighted discrepancy score (MWDS) for each item were calculated and reported. The mean weighted discrepancy score is used to identify the largest training needs and measures the “gap” between importance and preparedness while also taking into account the overall (average) importance of a competency as reported by the total number of respondents. Mean weighted discrepancy scores were calculated for each individual using the formula, ((Preparedness – Importance) multiplied by the (Importance Grand Mean)) (Bullard et al., 2013; Edwards & Briers, 1999; Robinson & Garton, 2008). When interpreting the results, a larger negative MWDS indicates a higher training priority. We report the mean score of importance, preparation, and MWDS for each individual competency because it represents a particular skill or action that is relevant to job performance. We also report an aggregate composite score for each “category” of competencies, which is the mean of all items within that category.

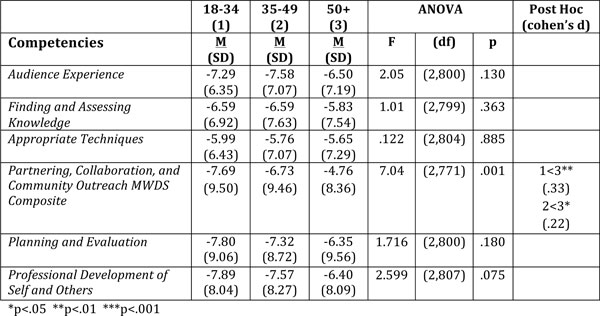

We used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonnferoni post hoc mean comparison to explore if training needs differ depending upon the age of individuals. To facilitate interpretation of the post hoc mean comparisons, we calculated Cohen’s d for each statistically significant result. Cohen’s d is an effect size measure that provides an assessment of the meaningfulness of the difference between groups (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Meaningful differences begin near 0.2, which may be considered small, while those approaching 0.5 are considered medium, and 0.8 large (Cohen, 1992).

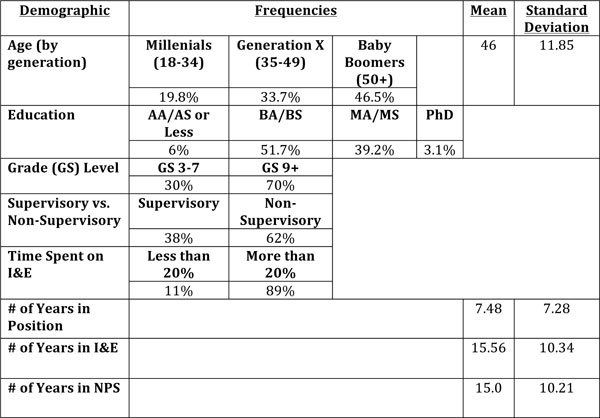

Table 1. Summary of the Demographics (N=1,032)

Table 1. Summary of the Demographics (N=1,032)

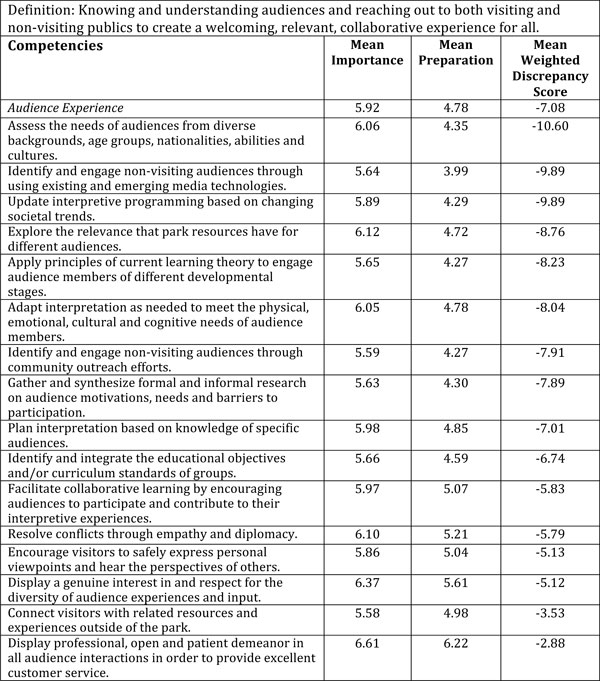

Table 2. Audience Experience: Mean Importance, Preparation, and MWDS Scores

Table 2. Audience Experience: Mean Importance, Preparation, and MWDS Scores

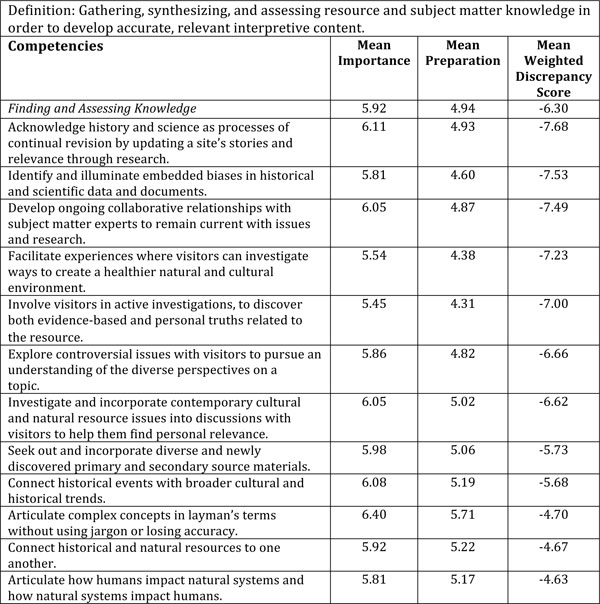

Table 3. Finding and Assessing Knowledge: Mean Importance, Preparation, and MWDS Scores

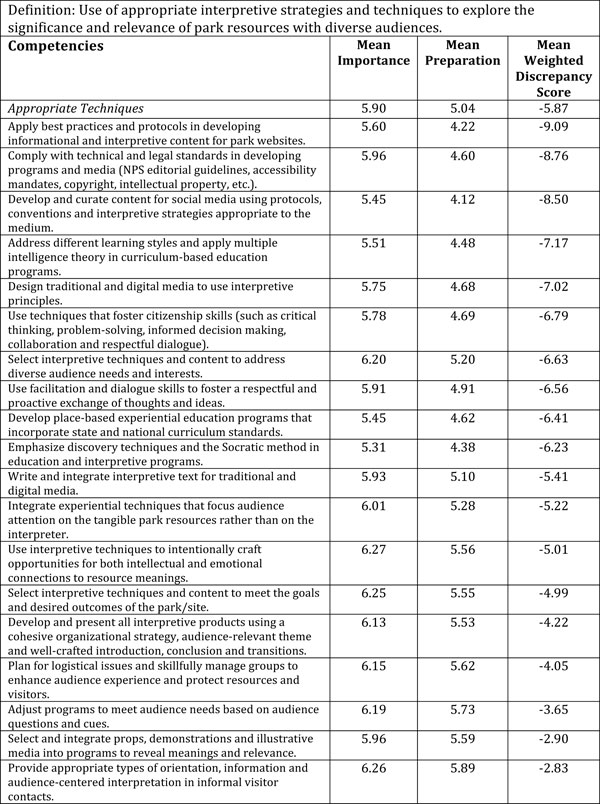

Table 4. Appropriate Techniques: Mean Importance, Preparation, and MWDS Scores

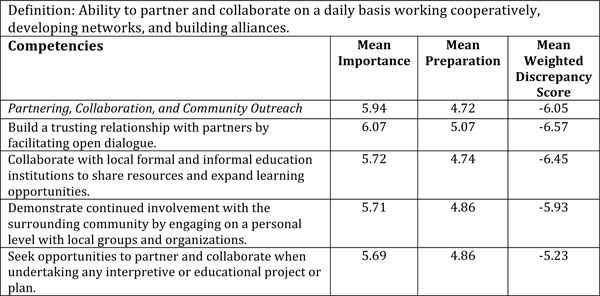

Table 5. Partnering, Collaboration, and Community Outreach: Mean Importance, Preparation and MWDS Scores

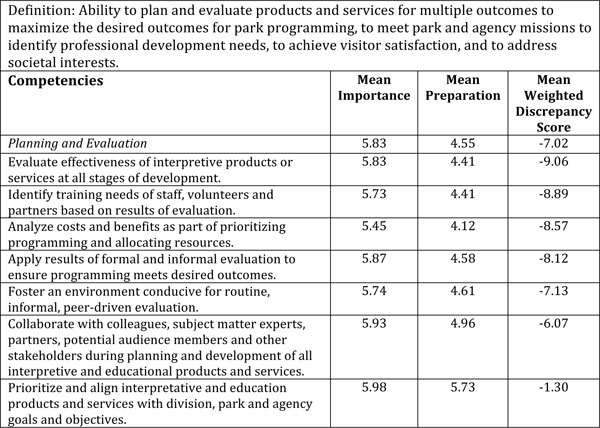

Table 6. Planning and Evaluation: Mean Importance, Preparation, and MWDS Scores

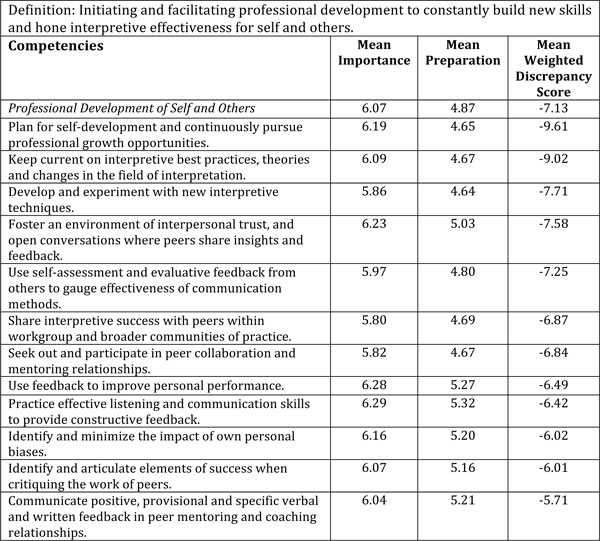

Table 7. Professional Development of Self and Others: Mean Importance, Preparation, and MWDS Scores

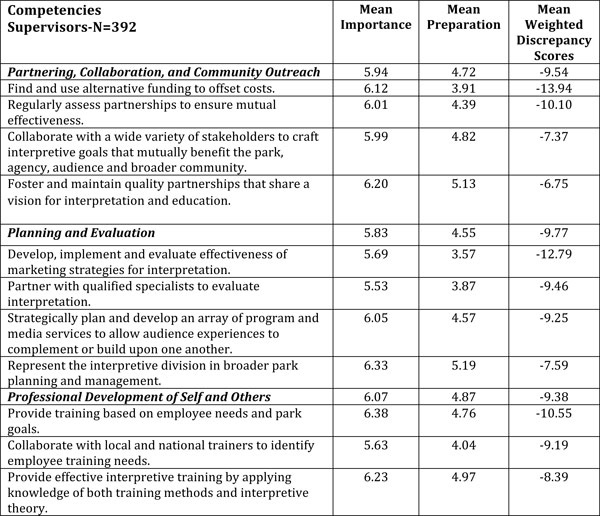

Table 8. Supervisory Competencies: Importance, Preparation, and MWDS

Table 9. ANOVA Comparison of Mean MWDS by Generations

Results

Description of Study Participants

At the conclusion of data collection, 1,032 respondents returned surveys with usable data, resulting in an effective response rate of 29.7%. Put simply, approximately one-third of all personnel identified by the Washington Support Office as having interpretation and education responsibilities in the NPS responded.

A large majority (89%) of respondents spend more than 20% of their time on interpretation and education responsibilities. The majority of respondents identified themselves as non-supervisors (62%). Study participants were well educated; 94% of respondents had a college degree. Close to half (42.3%) had an advanced degree. The respondents’ ages ranged from 22 to 78 years of age and almost half of participants (46.5%) were 50 years of age or older. This indicates that a large portion of the interpretation and education workforce is nearing retirement.

Importance Assigned to Interpretation and Education Competencies

The results (Tables 2–7) suggest that all competencies were relatively important with all ranked above the midpoint of the 7-point scale (4) with mean scores ranging from a high of 6.61 to a low of 5.31.

Level of Preparedness Assigned to Interpretation and Education Competencies

Results regarding preparedness suggest that respondents felt somewhat prepared for all of the competencies (Tables 2–7). The lowest mean for an individual item was 3.99, which is approximately the midpoint on the 7-point likert scale. The Planning and Evaluation category had the lowest preparedness mean (4.69).

Mean Weighted Discrepancy Scores for each Interpretation and Education Competency Category

The MWDS measures the “gap” between importance and preparedness while taking into account the overall importance of a competency as reported by the total number of respondents (Tables 2–7). The Appropriate Techniques category exhibited the smallest mean weighted discrepancy score (-5.87) whereas Professional Development of Self and Others had the largest (-7.13).

Within Audience Experience, the three competencies with the largest MWDS pertained to assessing the needs of diverse audiences, the use of media technologies for reaching non-visiting audiences, and updating programming to coincide with changes in society. In Finding and Assessing Knowledge, the three competencies with the largest MWDS pertained to acknowledging history and science as processes of continual revision by updating a site’s stories and relevance through research; identifying and illuminating embedded biases in historical and scientific data and documents; and developing relationships with experts to remain current with issues and research.

In Appropriate Techniques, the three largest MWDS all related to managing, developing, and maintaining social media, websites, and other electronic media. In Partnering, Collaboration, and Community Outreach, the three items with the largest MWDS pertained to building trusting relationships with partners, collaborating with educational institutions to share resources and expand educational opportunities, and engaging on a personal level with local groups and organizations. In Planning and Evaluation, the three items reflecting the largest training needs included the ability to evaluate interpretive products and services, identifying training needs of staff, volunteers, and partners based on evaluation results, and analyzing costs and benefits as part of prioritizing and allocating resources. Finally, in Professional Development of Self and Others, the three items with the largest MWDS pertained to planning and pursuing professional development, keeping current on interpretive best practices, theories, and changes in the field, and developing and experimenting with new interpretive techniques.

Mean Weighted Discrepancy Scores: Supervisors’ Interpretation and Education Competencies

In this study, we also measured 11 competencies in three categories that applied to supervisors exclusively: 1) Partnering, Collaboration, and Community Outreach, 2) Planning and Evaluation, and 3) Professional Development of Self and Others (Table 8). The largest MWDS pertained to the ability to find and use alternative funding to offset costs. The next largest MWDS pertained to developing, implementing, and evaluating marketing of interpretation programs.

Are there different training needs depending upon the age of individuals?

We divided respondents into three generational groups based on reported ages. Group 1 represented the “millennial” generation with an age range of 18–34 (n=162; 20%). Group 2 represented “generation X” with an age range of 35–49 (n=276; 34%), and Group 3 represented the “baby boomer” generation (n=381; 46%). We then compared the mean weighted discrepancy scores of the three groups using an ANOVA with post hoc comparisons. Significant results are reported in Table 9. For the competency category Partnering, Collaboration, and Community Outreach, the “millennial” generation and “gen X” had significantly larger MWDS on the composite, indicating greater training needs, than “boomers.”

Discussion

This study identified a range of competencies that were thought to be necessary for the provision of NPS interpretive services in the 21st century. Results also identified a number of strategic training needs. The largest mean weighted discrepancy scores indicate that training is needed to develop skills related to research literacy, engaging changing and new audiences, and effective use of available and emerging technologies.

The need for training focused on research literacy (ability to interpret and apply results to improve programs and inform decision-making) within the NPS appears to be paramount. Another recent needs assessment study on Visitor and Resource Protection in the National Park Service also found that skills related to understanding and using research to improve job performance were a training priority (Depper et al., 2016). In this study, evaluating the effectiveness of interpretation and keeping current on research appeared to be particularly important. Without the ability to utilize research and evaluate programs, either informally or formally, how will the practice of interpretation evolve and improve in the 21st century?

Developing skills related to engaging new audiences is also vitally important for the NPS if they wish to maintain relevance with the public (NPS, 2014). Specific competencies with larger training needs pertained to assessing the needs of diverse audiences, developing outreach for new and diverse audiences, identifying and engaging non-visiting audiences using current and emerging media, and updating programming based on shifting societal trends. Additional training regarding the development and use of research to identify audiences and non-visitors; their values, attitudes, and preferences; and the best ways to engage these different groups also appear necessary. These results suggest that staff need not only improved research literacy skills, but the ability to apply research findings to inform outreach and programming. For example, research suggests that women are concerned about safety, the lack of facilities, costs, and potential pests when considering participation in outdoor recreation (Johnson, Bowker, & Cordell, 2001). This information could aid program planning for women such as addressing safety concerns prior to interpretive hikes.

Moreover, a recent study of non-visitors to national parks revealed two major impediments, being too busy and travel time (Solop, Hagen, & Ostergren, 2003). African Americans and Hispanic Americans in particular did not visit because of too little information about the parks (Solop et al., 2003). Potential visitors need information regarding opportunities, ways to overcome potential barriers, and social norms regarding appropriate behaviors in park settings. Information is also needed for non-visitors who perceive that parks are in remote and distant locations and may be unaware of sites that are more accessible and urban proximate. This research suggests that engaging new audiences may require providing outreach efforts where these audiences live since they feel too busy to travel to parks. In addition, engaging new audiences in their own language may be required (Rodrigues, Clarke, & Alamillo, 2012). Training I&E employees to access, interpret, and apply relevant studies such as these should help build confidence and improve performance engaging new audiences.

Another overarching training need that arose from the study focused on using existing as well as emerging technology. Two competencies reflecting this gap were engaging non-visitors through media technology and applying interpretive best practices to content development on websites. These two items highlight that current NPS interpreters feel unsure of how to complete these job duties. This result may be influenced by the average age of I&E staff. Given that approximately half of respondents are 50 or older, their training may not have included effective use of current as well as emerging digital technology. This being said, if it is a goal to reach younger generations, dubbed by Russell (2014) “digital natives,” then online communications are essential. When looking to engage non-visitors Russell (2014) suggests conducting focus groups or other pre-targeting techniques to learn where these potential audiences are spending their time online and what types of material and content appeal to them. Training in the use of emerging digital technology could be invaluable for developing a 21st-century I&E workforce. The NPS is currently undergoing the process of developing digital communications competencies for the entire agency. These competencies could help guide I&E training in the future.

For supervisors, a few training needs were critical. These included providing advanced training in skills necessary for leadership and management such as identifying and securing alternative funding through grants, partnerships, and other “non-traditional” revenue sources as well as the ability to evaluate not only educational and interpretive products and programs but also to evaluate the marketing of these services.

Conclusion

In an effort to identify critical training needs in Interpretation and Education within the NPS, a team of subject matter experts from across the profession, including six academic institutions, the National Association for Interpretation, and the National Park Service, developed a comprehensive list of KSAs relevant to providing and managing interpretation in the 21st century. Using this list of competencies, we then implemented a study that investigated NPS I&E employees’ beliefs regarding how important and how well prepared they are in fulfilling these specific competencies that are necessary to perform at the highest levels.

The National Park Service has a long history of advancing the profession of interpretation. This effort is useful for organizations such as the National Association for Interpretation (NAI) as well as others that provide interpretation and educational programming by identifying a comprehensive list of competencies related to providing and managing interpretation services. The process of reviewing and updating the competencies associated with I&E also reiterated the need for the field to continually test the “best practices” in interpretation and education that are assumed to facilitate the co-creation of meaningful experiences and thereby meet the needs of the 21st-century public. Few studies to date have explicitly tested the efficacy of many of the best practices employed today (e.g., Stern & Powell, 2013; Powell & Stern, 2013a,b). Through experimentation, refinement, and periodic evaluation/validation of these practices, not only will the NPS I&E program excel, but also the broader field will continue to ensure that techniques and approaches promoted in training and certification efforts are supported by the “best available science” to enhance visitor outcomes.

References

Brownlee, M. T. J., Powell, R. B., & Hallo, J. C. (2012). A review of the foundational processes that influence beliefs in climate change: Opportunities for environmental education research. Environmental Education Research, 19(July 2015), 1–20. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.683389

Bullard, S., Coble, D., Coble, T., Darville, R., Rogers, L., & Williams, P. S. (2013). Producing “society-ready” foresters: A research-based process to revise the Bachelor of Science in Forestry curriculum at Stephen F. Austin State University. Nacogdoches, TX.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20182143.

Council on Environmental Quality, Department of Agriculture, Department of the Interior, & Environmental Protection Agency. (2011). America’s great outdoors: A promise to future generations. Washington DC. doi:.gov/ AmericasGreatOutdoors.

Depper, G. L., Vigil, D. C., Powell, R. B., & Wright, B. A. (2016). Resource protection, visitor safety, and employee safety: How prepared is the National Park Service? Park Science, 32(2), 18–24.

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2009). Internet, mail and mixed- mode surveys: The tailored design method (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

Edwards, M. C., & Briers, G. E. (1999). Assessing the inservice needs of entry-phase agriculture teachers in Texas: A discrepancy model versus direct assessment. Journal of Agricultural Education, 40(3), 40–49. doi:10.5032/jae.1999.03040

Hammitt, W. E., Machnik, L. K., Rodgers, E. D., & Wright, B. A. (2007). Workforce Succession and Training Needs Among National Park Service Program Managers. Park Science, 24(2), 72–77.

Johnson, C. Y., Bowker, J. M., & Cordell, K. I. (2001). Outdoor recreation constraints: An examination of race, gender, and rural dwelling. Southern Rural Sociology, 17, 111–133. Retrieved from http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/3050

Machnik, L. K., Hammitt, W. E., Drogin Rodgers, E. B., & Wright, B. A. (2007). Planning for Workforce Succession Among National Park Service Advanced-Level Natural Resource Program Managers: A Gap Analysis. Society & Natural Resources, 21(1), 50–62. doi:10.1080/08941920701329694

Mccown, R. S., Laven, D., Manning, R., & Mitchell, N. (2012). Engaging new and diverse audiences in the national parks: An exploratory study of current knowledge and learning needs. The George Wright Forum, 29(2), 272–284.

National Park Service. (2014). Achieving relevance in our second century. Washington, DC: National Park Service.

National Parks Second Century Commission. (2009). Advancing the national park idea: Connecting people and parks committee report. Washington D.C.

National Park System Advisory Board Education Committee (2014). Vision paper: 21st century National Park Service Interpretive skills. Washington D.C.

Powell, R. B., & Stern, M. J. (2013a). Is it the program or the interpreter? Modeling the influence of program characteristics and interpreter attributes on visitor outcomes. Journal of Interpretation Research, 18(2), 45–60.

Powell, R. B., & Stern, M. J. (2013b). Speculating on the role of context in the outcomes of interpretive programs. Journal of Interpretation Research, 18(2), 61–78.

Robinson, S., & Garton, B. (2008). An assessment of the employability skills needed by graduates in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources at the University of Missouri. Journal of Agricultural Education, 49(4), 96–105. doi:10.5032/jae.2008.04096

Rodriguez, D., Clarke, T., & Alamillo, J. (2012). Engaging and connecting non-traditional minority audiences and national parks: Literature review and critical analysis. Camarillo, CA.

Russell, J. T. (2014). Driving the digital message in a digital world. The Public Manager, 14–16. Retrieved from https://www.td.org/Publications/Magazines/The-Public-Manager/Archives/2014/Winter/Driving-a-Digital-Message-in-a-Digital-World?mktcops=c.govt&mktcois=c.public-sector

Skibins, J. C., Powell, R. B., & Stern, M. J. (2012). Exploring empirical support for interpretation’s best practices. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17(1), 25–44.

Solop, F. I., Hagen, K., & Ostergren, D. (2003). Ethnic and racial diversity of National Park System visitors and non-visitors. NPS Social Science Program, Comprehensive Survey of the Amercian Public, Diversity Report, 1–13.

Stern, M. J., & Powell, R. B. (2013). What leads to better visitor outcomes in live interpretation? Journal of Interpretation Research, 18(2), 9–43.

Stern, M. J., Powell, R. B., & Hill, D. (2014). Environmental education program evaluation in the new millennium: What do we measure and what have we learned? Environmental Education Research, 20(5), 581–611. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.838749

Stern, M. J., Powell, R. B., Mclean, K. D., Martin, E., Thomsen, J. M., & Mutchler, B. A. (2013). The difference between good enough and great: Bringing interpretive best practices to life. Journal of International Affairs, 18(2), 79–100.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Weddell, M. S., Fedorchak, R., & Wright, B. A. (2009). Partnership Behaviors, Motivations, Constraints, and Training Needs Among NPS Employees. Park Science, 26(2), 87–91.

Weddell, M. S., Fedorchak, R., & Wright, B. A. (2013). Improving National Park Service Partnerships: A Gap Analysis of External Partners. Park Science, 29(2), 13–17.

Wright, B. A., & Makay, A. N. (1995). National Park Service Interpretation Training Needs Assessment. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.