Susan Caplow

Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences

University of Montevallo, Station 6176

Montevallo, AL 35115

scaplow@montevallo.edu

Phone: 206-665-6176

Fax: 205-665-6186

Abstract

Interpretive programs can encourage the development of pro-environmental behavior, but visitors do not arrive as blank slates. Instead, their previous experiences interact with new programs to produce iterative change over time. Animal ambassadors can help facilitate these changes, but animal specialty organizations have largely been excluded from research exploring audiences and programs in free-choice learning settings. This study fills that gap by exploring differences between audiences at organizations with different types of missions. Using survey and interview data and value-belief-norm theory as a framework, I compare learners across three animal-themed interpretive facilities. Visitors were similar on some sociodemographic/social-psychological metrics, but they also differed in ways that reflect the institutional mission at each organization. Most notably, specialty organizations reach audiences who are sensitive to animal/environmental welfare but are uncomfortable with zoos. Interpreters can replicate these methods at their own organizations or consider how the visitors in this study can help them better understand their own context. More knowledge about their visitors helps interpreters better design programs to achieve desired program outcomes and facilitate pro-environmental behavior.

Keywords

values, beliefs, norms, interpretation, pro-environmental behavior, animals

Are We Preaching to the Same Choir? A Mixed-Methods Comparison of Audiences at Animal-Themed Interpretive Facilities

Nature interpretation can compel participants to shift attitudes and beliefs and engage in pro-environmental behavior (Kim, Airey, & Szivas, 2011; M. Stern & Powell, 2013). However, learners do not arrive at interpretive programs as blank slates (Falk, Heimlich, & Foutz, 2009). Instead, learners enter with rich, varied previous experiences that influence how they engage with and internalize education programs (Schultz & Tabanico, 2007). Thus, understanding the visitor is crucial to understanding education program outcomes, which in turn helps educators better design programs to meet learning goals (Clayton, Fraser, & Saunders, 2009).

Interpretation is defined as “a communication process that forges emotional and intellectual connections between the interests of the audience and the meanings inherent in the resource” (Brochu & Merriman, 2015; Knapp & Benton, 2004). Nature interpretation emphasizes emotions and personal meaning-making, which are both strong forces for personal change (Archer & Wearing, 2003; Rickinson, 2001). Best practices in nature interpretation have been analyzed at a large scale and were found to contribute positively to both visitor satisfaction and behavioral intentions post-program (M. Stern, Powell, Martin, & McLean, 2012).

Interpretive programs typically occur within free-choice learning contexts (Clayton & Myers, 2009). Free-choice learning happens outside of the formal schooling environment, is voluntary, and is driven by identity-related needs (Falk, 2005; Falk & Storksdieck, 2010). Settings associated with both free-choice learning and interpretation include museums, science centers, zoos, aquariums, botanical gardens, and nature centers (Falk & Dierking, 2002). Research has shown that a higher proportion of free-choice learners are white, liberal, female, and highly educated than the general population (Falk et al., 2009). These same demographic groups also tend to score higher on a variety of social-psychological environmental measures than the general population (Nooney, Woodrum, Hoban, & Clifford, 2003). While this self-selection may result in educators “preaching to the choir” (Storksdieck, Ellenbogen, & Heimlich, 2005), reinforcing pre-existing values, beliefs, and norms is an important learning outcome (Ellenbogen, 2003). In fact, incoming characteristics, knowledge, and goals have measurable impact on educational outcomes (Falk & Adelman, 2003; Falk, Storksdieck, & Dierking, 2007). In particular, message reinforcement can move individuals towards new decisions to take action for the environment (Falk, 2005). In interpretive best practice, knowing one’s audience is as important as knowing the resource itself (NPS, 2002), but organizations often lack the resources to undertake systematic analysis of their audiences; studies incorporating diverse organizations can help diverse institutions better understand and plan for their own audiences.

Animal-themed facilities represent a particularly fruitful space for encouraging pro-environmental behavior. Animals are used extensively in environmentally themed interpretive programs; animals can activate an empathetic response, which can lead to behavior change (Young, Khalil, & Wharton, 2018). Animal-themed facilities attract a more diverse audience than other environmentally themed attractions (Khalil & Ardoin, 2011), positioning them to deliver environmental messages beyond the choir. Also, while animal-themed entertainment is still widely popular, visitors are becoming increasingly uncomfortable with animal captivity for human purposes (Knight & Herzog, 2009). Many zoos and aquariums have rewritten their missions to focus on conservation and education, justifying their use of captive animals (Hutchins, Smith, & Allard, 2003; Miller et al., 2004; Patrick & Caplow 2018; Patrick, Matthews, Ayers, & Tunnicliffe, 2007). Specialty institutions may offer opportunities to interpret natural resources to individuals who are uncomfortable with animal captivity but are otherwise primed for the adoption of new environmental behaviors.

Previous studies examine free-choice audiences either at one institution or one type of institution (Khalil & Ardoin, 2011), but there are few studies comparing across organizations and even fewer comparing across types of organizations (Ballantyne, Packer, & Hughes, 2008; Dierking, Burtnyk, Buchner, & Falk, 2002). Additionally, while quantitative research has demonstrated cognitive gains from exposure to environmental education, the shaping of environmental values over time has been under-researched (Hart & Nolan 1999; Rickinson 2001; Storksdieck, Ellenbogen, & Heimlich, 2005).

Using a mixed-methods approach, I aim to better understand how visitors self-select for experiences based on their incoming views and characteristics. I ask: What experiences, values, beliefs, and behavioral norms do participants bring to education programs, and how do learners differ across different types of organizations? I postulate that different types of organizations attract fundamentally different audiences in terms of sociodemographic and social-psychological variables, and that qualitative interview data will uncover additional audience characteristics not captured by survey data. Following the interpretive practice of “knowing your audience” (Brochu & Merriman, 2015), interpreters can use this information in two ways. First, these methods can be replicated at other sites to better understand audiences in those contexts. Second, in lieu of primary data collection, interpreters can consider conceptually how their organization’s mission and values relate to the cases in this study so they can better tailor messages to their audiences to facilitate behavior change among other shifts in environmental values, beliefs, and norms. (See Jacobson, McDuff, & Monroe, 2006, for a comprehensive list.) My field sites include one Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA)–accredited institution (North Carolina Aquarium), one research facility (Duke Lemur Center), and one wildlife sanctuary (Carolina Tiger Rescue).

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods

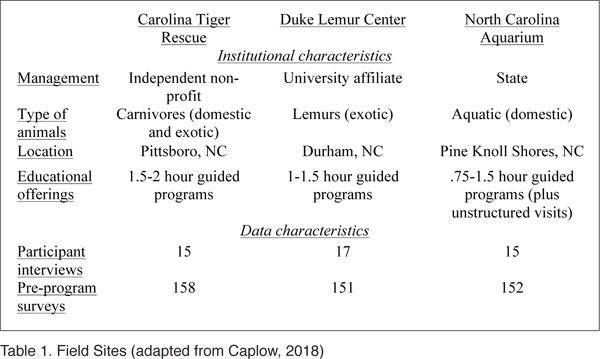

This project is a mixed-methods comparative case study with an exploratory design (Creswell & Clark, 2007) of visitors at three animal-themed organizations. Case studies explore phenomenon in-depth and in-context and are appropriate when the researcher has little control over the phenomena in question (Yin, 2009). Exploratory design involves first collecting qualitative data (“exploring” the topic) and then implementing further data collection in order to test for distribution and prevalence of themes (Creswell & Clark, 2007). This method cultivates preliminary understanding of the phenomena at hand before larger-scale data collection occurs. Finally, comparing multiple cases sheds light on how the characteristics of each organization and programs interact with incoming learner characteristics. The three “case” organizations all have conservation and education goals, but they differ by institutional mission and animal type (Table 1). In this study, I collected interview data and survey data, which enabled me to first explore visitor narratives and then systematically compare visitor populations across sites.

Field Sites

Carolina Tiger Rescue (CTR) was founded in the early 1980s as a breeding facility for rare carnivores. In 2001, they stopped breeding to focus exclusively on wild animal rescue. Its mission is “saving and protecting wild cats in captivity and in the wild” (CTR, 2012). It houses approximately 60 to 70 animals, including large/small cats and frugivorous carnivores. Volunteers run public tours mostly on the weekends, and visitors are not allowed to enter the sanctuary unaccompanied.

Duke Lemur Center (DLC) was founded in 1966 as a primate research facility. It houses approximately 250 prosimian primates from 21 species, which is the largest collection of lemurs outside of Madagascar in the world. DLC’s mission is, “Promote research and understanding of prosimians and their natural habitat as a means of advancing the frontiers of knowledge, to contribute to the educational development of future leaders in international scholarship and conservation, and to enhance the human condition by stimulating intellectual growth and sustaining global biodiversity” (DLC, 2012). DLC conducts research, breeds lemurs for conservation, offers guided education programs, and leads conservation efforts in Madagascar.

The North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores (NCA) was founded in 1976 as a teacher resource center. It keeps species native to North Carolina, and its mission is “inspiring appreciation and conservation of North Carolina’s Aquatic Environments” (NCA, 2012). NCA is the only facility in this study that allows the public to visit without a guide, but I focus on its specialty guided tours, which take visitors behind the scenes for an additional fee.

Theory

Theory

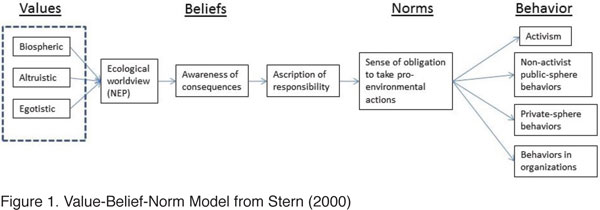

I used value-belief-norm (VBN) theory (P. C. Stern, Dietz, Abel, Guagnano, & Kalof, 1999) to structure interview content and identify key social-psychological metrics by which to compare learners across sites (Figure 1). VBN starts with deeply personal/stable environmental values and moves to understanding consequences, recognizing accountability and responsibility, and then finally to taking action on behalf of the environment (Chawla & Cushing, 2007; Hungerford & Volk, 1990). Regression analysis has supported VBN as “the best available social-psychological account of non-activist support for the goals of the environmental movement” (P. C. Stern et al., 1999: 91). I chose VBN for this analysis because it identifies learner characteristics that are closely associated with the likelihood of engaging in pro-environmental behavior. However, as statistical determinants of environmental behavior have been a controversial area of research (Kaiser, 1998; Nordlund & Garvill, 2002; Steg & Vlek 2009), I use mixed methods to better capture the nuances of visitor perceptions of environmental behavior; in this way, I also use VBN as an organizing structure to help interface quantitative and qualitative data.

Data

I collected interviews in the summer of 2012 and both interview and survey data in the summer of 2013 (Table 1). I recruited interviewees at the beginning of interpretive programs. I described my study, distributed an information sheet, and asked visitors to provide their contact information if they consented to be interviewed on a later date. In 2013, I asked participants to fill out the survey in advance of the program, as visitors at all three sites were told to arrive anywhere from five to 15 minutes early. The survey also asked for contact information if they consented to be interviewed. If a party arrived less than five minutes before the program began, I did not administer the survey.

I conducted two types of interviews. In both 2012 and 2013, I asked general questions about interviewee’s environmental values, beliefs, and norms. In 2013, I drew frequently mentioned environmental experiences from the 2012 interviews to prepare 30 experience cards for participants to organize in whatever way made the most sense to their personal experience (Caplow, 2014). This exercise improved participants’ ability to verbalize abstract concepts such as values, which can be difficult to do without context or feedback (Burgess, Limb, & Harrison, 1988). While I analyzed data from both years, the exercise sparked better conversation and introspection about environmental values, beliefs, and norms.

The survey included metrics capturing the variables in the VBN framework plus a few additional types of data. The first section asked about previous experiences with animal/environmental facilities and party characteristics. The second section administered the Animal Attitudes Scale (AAS) (Herzog, Betchart, & Pittman, 1991). This metric captures sensitivity to animal welfare issues. I included it because the relationship between animal welfare attitudes and environmentalism is not well-studied (Herzog & Golden, 2009), but it is possible that animal welfare issues appeal to a different subset of the population than general environmental topics.

The third section consisted of three metrics capturing concepts in the VBN framework. First, I used a values orientation scale by de Groot and Steg (2007b), which is a shortened version of Schwartz’s values scale, focusing on values dimensions shown to be associated with environmentalism (altruistic, biospheric, egotistic). Second, the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale is one of the most frequently used environmental metrics in the literature (Dunlap, 2008; P. C. Stern, Dietz, & Guagnano, 1995). I used the 15-item scale, which is the most reliable scale according to meta-analysis (Hawcroft & Milfont, 2010). The third metric captured the norm activation component of VBN theory (Schultz et al., 2005), including awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and behavioral norms (P. C. Stern, 2000). In this metric, participants rate the severity of environmental problems and their responsibility for those problems. The final section of the survey collected demographic information.

Data Analysis

I coded interview transcripts in ATLAS.ti using qualitative research best practices (Saldana, 2009). First, I coded data attributes so that I could organize by field site, type of data, and 2012 versus 2013 (Lofland, 2006). Next, I conducted structural coding in which I isolated elements of the VBN variables (valued object, threat to valued object, etc.) as well as any other areas of interest. For example, I coded for “science/research” and “quality of care” so that I could isolate when those topics were discussed. I then engaged in a cycle of pattern coding, in which I developed major themes based on the clusters of data (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Finally, I selected quotes to succinctly capture each theme.

I analyzed survey data using Stata v.13. I first explored differences across sites using two-way t tests (for political orientation), chi-squared tests (for educational attainment), and one-way ANOVA (for all other variables). I then used multiple linear regression to model VBN variables as a function of site, controlling for demographics (gender, age, political affiliation, education, income, race, and environmental professionalism), and one measure of social desirability (providing contact information). I also ran correlations between all VBN metrics and obtained variance inflation factors to test for multicollinearity among regression variables.

Results

Pre-program Survey

I collected 461 pre-program surveys at the beginning of 68 interpretive programs across the three sites. Almost 82% of the adult visitors agreed to participate in the survey; the majority of the 18% who did not take the survey arrived within five minutes of the start of the program.

Party characteristics and previous experiences.

Party characteristics and previous experiences.

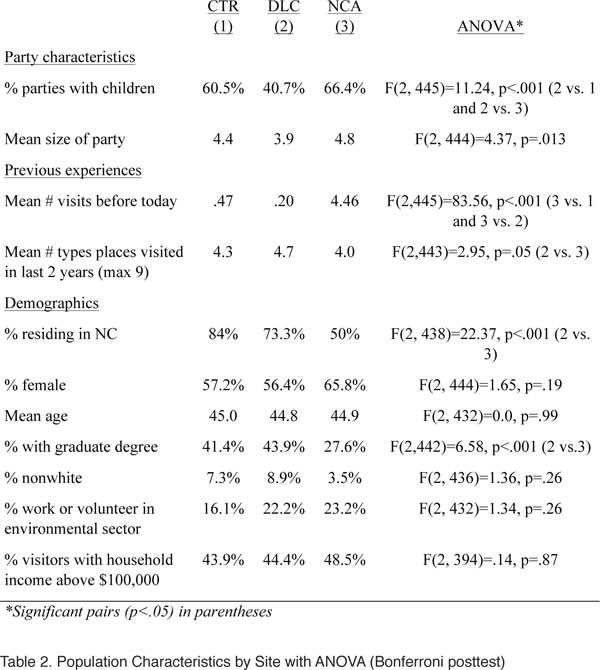

The average party size ranged from 3.9 at NCA to 4.8 at DLC (Table 2). Significantly fewer parties at DLC included children than both CTR and NCA. On average, respondents had visited NCA 4.5 times before the program when they took the survey, which is significantly more than CTR (respondents had visited an average of .47 times previously) and DLC (respondents had visited .19 times previously).

I measured previous experiences by asking participants if they had visited any of the following facilities in the last two years: zoo, aquarium, nature center, state or national park, natural history museum, circus, science center, botanical garden, animal rescue, or other. Participants at DLC have visited significantly more of those locations (4.7) than participants at NCA (4.0).

Visitor demographics and experiences.

Participants at the three sites were statistically indistinguishable on gender, age, race, environmental work/volunteering, and income. Participants were wealthier, more educated, liberal, and female than the general US population: females comprised 60% of the respondents; 45.6% of respondents reported a household income above $100,000, whereas the 2012 national average was $51,000 (Noss, 2014); 38% have a graduate degree, well above the national average of 13% (Ryan & Bauman, 2016); and 45% identified as Democrats, with 19% identifying as Republican, and the rest as independent, undecided, or other). The population was over 90% white at all three sites.

Participants differed on educational attainment: more people with less than a college degree and fewer with a graduate degree attended programs at NCA than CTR and DLC (χ2(6, N = 45) = 23.0334, p<.001). Fewer Democrats attended programs at NCA (37%) than at CTR (46%) or DLC (53%), and more Republicans attended programs at NCA (29%) than CTR (14%; t (277) =-8.04, p<.01) or DLC (13%; t (286) =-7.60, p<.01).

VBN results.

VBN results.

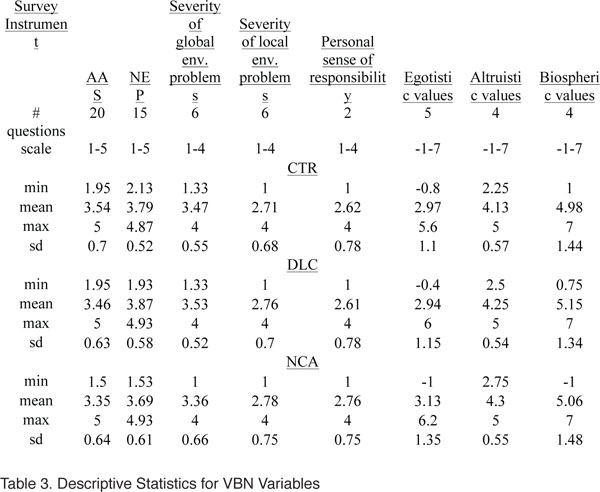

All VBN variables are composed of the mean scores of multiple Likert-scale questions (Table 3). VBN analyses use the mean score for each metric; Cronbach alpha scores are above .7 for all variables except egotistic values (barely missing the cutoff at .67), suggesting acceptable internal consistency (Nunnaly, 1978).

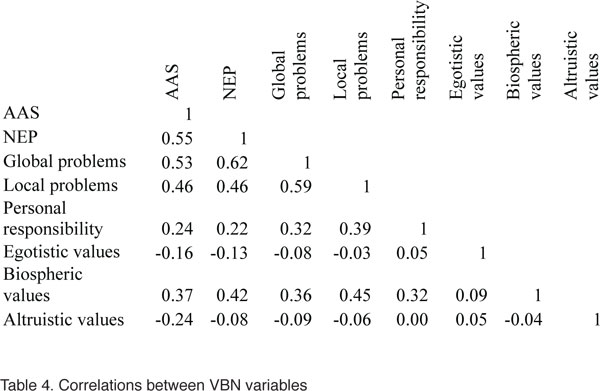

AAS, NEP, and perceptions of local and global environmental problems scores were all correlated above .45 (Table 4). Personal sense of responsibility for environmental problems was correlated with perceptions of global (.32) and local problems (.39). Biospheric values correlated with all other VBN variables at above .3. Egotistic and altruistic values show little correlation with the other VBN variables—the only correlation above .2 is between altruistic values and AAS, but the direction is negative, meaning that as altruistic values rise, AAS scores fall.

Linear regression.

Linear regression.

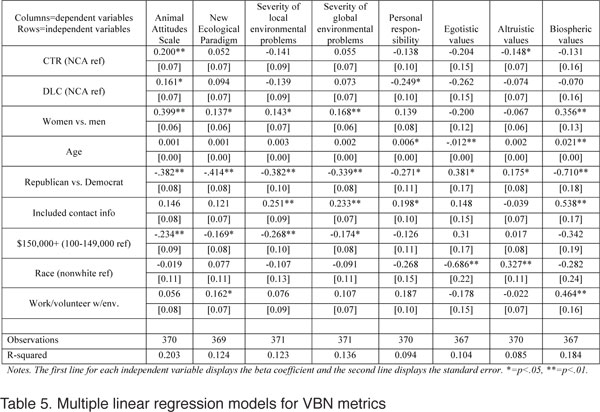

I ran linear regression models controlling for gender, age, race, political orientation, income, and contact information (Table 5). I originally included education in the model, but removed it because the effects were inconsistent, a likely result of combining those who were still in high school or college with those who never obtained degrees.

Both CTR and DLC visitors scored higher on the AAS than NCA visitors, NCA visitors feel a greater sense of personal responsibility for environmental problems than DLC visitors, and NCA visitors had higher altruistic values scores than CTR visitors. I report unstandardized beta coefficients, so the coefficient is relative to the scale.

Gender explained a significant amount of variance for AAS, NEP, global problems, local problem, and biospheric values; in all cases, females displayed higher values. Older individuals had a higher sense of personal responsibility and biospheric scales, and lower egotistic values. Political orientation explained a significant amount of variance for all VBN variables: Republicans had lower scores than Democrats for AAS, NEP, global problems, local problems, personal responsibility, and biospheric values, and had higher egotistic and altruistic scores. Nonwhite participants had higher egotistic values scores and lower altruistic values scores than white respondents.

Individuals who work/volunteer for environmental organizations had higher NEP scores and biospheric values scores than those who do not. The wealthiest respondents in the survey had lower scores on the AAS, NEP, global environmental problems scale, and local environmental problems scale than the next-highest income reference group. Individuals who filled out contact information had higher scores for biospheric values, personal responsibility, and perceptions of the severity of both local and global problems. I tested for multicollinearity among independent variables and they all had variance inflation factors (VIF) smaller than 2.5, suggesting sufficient independence for analysis (Allison, 2012).

Interview Results

Interview participants were diverse in age (average 47 years, range 21 to 82) and gender (55% women). In 2013, I also used survey data to sample for diversity in political affiliation, income, and whether the person had children. I did not find any systematic differences across sites in interview content, thus I present interview results as one group as opposed to three.

VBN narratives.

All participants were distinctly adherent to environmental values, beliefs, and norms. Values and beliefs were heavily intertwined within a single narrative: Nature is inherently/instrumentally valuable, interconnected, and in balance, and when humans interfere we create problems/crisis. For example, this interviewee discusses biospheric values while evoking the idea of the inappropriateness of human domination, one of the dimensions of the NEP:

Well, I kind of have a hard time figuring out why [animals] need to be important. You know, it’s like they are—they just are important. ’Cause they’re alive. And why do we have the right to say whether they’re important or not, you know? (DLC 42)

This second interviewee evokes both altruistic values and the interconnectedness of nature, another key NEP element:

I mean everything’s intertwined in my mind, every piece of this world is intertwined and has an effect on another part of the planet, the vegetation, animals, whatever it is. We’re all connected somehow. (CTR 566)

This next participant envisions a future in which we do not respect the balance of nature, and in the end we suffer for it, while simultaneously referencing altruistic values:

Society will not learn until it comes to a screeching halt, or it comes to the point where people are screaming Armageddon because things are so bad. I think it will take us literally, for our empires to fall, and fall back, before we start finally realizing the importance of nature, and how much we depend on it, and how much we take it for granted. (NCA 521)

Only one interviewee professed a belief in limitless human ability to solve ecological problems (a belief in line with the Dominant Social Paradigm); all other interviewees expressed concern about humankind’s ability to destroy itself.

Egotistic values was the only VBN concept that appeared to be disconnected from the VBN narrative. Participants operationalized egotistic values when discussing the education experience itself, not in relation to larger environmental beliefs:

I like to learn new things so from a personal perspective, from a selfish perspective, I just like learning things, I like to see the animals; what they look like, what they do. (NCA 542)

Behavioral assessment.

I asked interviewees to identify the most important behaviors to help the environment and to assess how they perform on those behaviors. All interviewees engaged in some form of pro-environmental behaviors; at least three people mentioned behaviors from each category of the VBN framework: private sphere behaviors, activism, public non-activist behaviors, and behavior in organizations.

Interviewees cited recycling more than any other behavior: Out of 47 interviewees, 42 (89%) mentioned recycling. No one questioned the efficacy of recycling. Instead, recycling was an indicator of an environmentally friendly life. Regardless of the actual environmental behaviors individuals reported, interviewees assessed themselves as “pretty good, but could do better.” On one end of this spectrum, this learner only mentions recycling and litter pick-up:

I’d say I would do pretty well, I recycle, and when I go on walks a lot of the time I like to pick up trash, if it’s not too difficult to in like, my hands. (DLC 67)

The next interviewee describes a bit more engagement in pro-environmental behavior, but their commitment is somewhat inconsistent:

I like to say, that I was green before it was popular to be green! … I could probably do even more here at the house, you know with the recycling, some of the cans and stuff. Sometimes I’ll just say, oh, you know I don’t want to take the time to do this. I’ll just pitch it instead, that sort of thing. Probably could even be a little more conscious with water, of turning the water on and just letting it run while you’re doing something, kind of forgetting that, oh! (NCA 112)

Finally, the most extreme example of an interviewee assessing their performance as “pretty good” comes from this individual who has avoided using air conditioning all summer (the interview was conducted in Raleigh, North Carolina, in August):

I would try to think I do pretty good. You know, I shut down stuff all the time, with power strips, shut those things down, leave for work the morning. I try not to use, I’m not using the AC right now. I haven’t been all summer really so far. (CTR 566)

Interviewees did not assess their efforts against best practices in environmental behavior; instead they used both internal and external norms to set their personal expectations.

Political orientation.

All interviewees expressed pro-environment values, beliefs, and norms regardless of political orientation. One interviewee who spent much of the interview berating liberals and environmentalists for what they perceived to be irrational and damaging environmental policies embraced similar behaviors to self-professed environmentalists:

I try to recycle. I try not to waste resources. I’m careful with the amount of electricity I use. But I’m sure not going to get an electrical car! And I don’t drive an SUV either. Why have a heavier vehicle that you don’t really need? I think a lighter vehicle is more in line, and SUVs are very wasteful. They weigh 500–1,000 pounds more…. I try to not be wasteful with food. And I can see benefits from insulating your house. Just practical ways. (DLC 39)

Even though the survey data suggest that Republican respondents adhere less strongly to environmental worldviews and behavioral intentions, politically conservative interviewees all supported environmental protection and engage in pro-environmental behavior.

Animal welfare.

Interviewees identified strong qualifiers for the justification of animals in captivity, assessing organizations based on a combination of the institutional mission (why they keep the animals) and the quality of the care they perceive at the facility. In all cases, their experience depends on animal welfare criteria being met:

There’s always this, I guess internal battle, seeing animals in cages … knowing that that’s not their natural habitat, and … it’s always hard to balance that out, also wanting to maintain some genetic diversity, by keeping lemurs that are going to be protected … it’s the same thing with zoos for me, kind of an internal battle. (DLC 37)

[The] zoo was at least somewhat considerate of the animal but I never really liked the idea, because I read about them, in their natural habitat, you know and these huge trees and rocks and places for it to have an area on a ledge two thousand feet above, instead of a box. I’m not a big fan of animals caged but the cats place [CTR]—that’s one thing, they couldn’t exist their habitat. (CTR 550)

It depends on the animal, and it depends on the situation…. I mean they had some really huge tanks, and you don’t feel quite so bad about something like that, when they have so much space, it’s not like an elephant in the circus that gets tied to a stake, and they’re not allowed to move from that stake, and they get beaten, that makes me sad, but … I didn’t get that feel when I was there. (NCA 112)

Interviewees expressed high levels of concern for animals in captivity and wanted to see organizations demonstrate adequate purpose and quality care. Along these lines, individuals at all three sites articulated discomfort with other types of captivity, mostly zoos:

I mean, I love the Aquarium. I’m not so much of zoo person…. (NCA 184)

And I’m not quite into zoos, but…[I like] actually getting to observe a different kind of wildlife that I really had no prior knowledge of [at DLC]. (DLC 552)

I’m kind of iffy on [zoos and aquariums]…. And for instance, Carolina Tiger Rescue, it’s not really a zoo, but it’s similar to that in that it has animals somewhat in captivity. But it’s also more purpose and something good, from what I can tell anyway. (CTR 566)

Change.

Participants described increasing agency, self-awareness, conviction, care, work ethic, time availability, and knowledge in regards to environmental protection:

I’ve always had respect [for the environment], but … I become more cognizant of my own behaviors, and tried to change those, as I’ve grown up and realized—and I start realizing how what I do can impact the environment. (DLC 37)

I probably feel more strongly now, of course … because I’m retired now, and I have more time, I feel more strongly about these things because I get to read more, and I also have time to be more [politically] active. (CTR 571)

I guess it’s broader…. I started out with this is our camp, and this is my dog, and I don’t want to see anything happen to either one of them. And I’ve been able to take a wider perspective, include more people, more species. I think that’s common in anybody as they age, more knowledge gives you more insight, as your brain matures you can grasp a lot of concepts. (CTR 551)

No interviewees stated that as they have gotten older, they have become less concerned or more pragmatic about the environment.

Interviewees reported an increase in sensitivity over time. Seven interviewees saw this sensitivity manifest as an increasing difficulty with eating meat:

Yeah, I don’t eat meat anymore. And a lot of that is because of treatment of cows and chickens… I was talking to my kids about it last night…and my son at [college] took [a course about it]. And so, it kind of reinforced my decision. He’s like; ‘I’m almost thinking about being a vegetarian!’ And, you know, it’s something that I thought about for years, before I actually decided to do it. (NCA 184)

This interviewee highlights the often-lengthy path to vegetarianism, indicating that repeated exposure to the concept was necessary to create action.

Religion and stewardship.

Even though I did not ask about this topic directly, at least 15 interviewees cited Christian underpinnings for their beliefs. Some interviewees wove religious justification into their general environmental beliefs, connecting them to themes of biospheric values, balance of nature, and inappropriateness of human domination:

Well I guess it’s cause we’re all God’s creatures, and deserve the right to our spaces and what have you…. It’s like an ecosystem, and when you disrupt part of that system, whatever part of it it is, the whole thing doesn’t run well … you need that balance, of … everything. (NCA learner 112)

In other cases, interviewees specifically state the belief that God gives us dominion over animals, conjuring a hierarchical model with an emphasis on altruistic value of nature:

I think animals were given to us in nature by God to enhance our lives, but we have a responsibility not to misuse them. But we are their keepers, and they are for our benefit. But that doesn’t give us the right to be cruel, or not take care of them in any manner. In fact, just the opposite. (DLC learner 39)

The faith-based reasoning posits that all of God’s creatures have value, but the stewardship responsibility emphasizes the belief that humans have dominion over animals. Placing humans in a higher position was further emphasized by interviewees when discussing priorities with animals and humans:

I’m educated enough to know intellectually they’re not our equals, which means emotionally they are not sophisticated enough to be our equals, and I’m enough of a pragmatist to feel that there are other bigger issues in the world that supersede whether every dog has a clean bed to sleep in or not. (CTR learner 551)

Discussion

VBN metrics proved to be useful in an animal-themed context. Visitors at all three sites subscribe to an ecological paradigm and care about animals, but the magnitude of their adherence to environmental values, beliefs, and norms differs across sites. Understanding their visitors in these ways can help educators better activate learners’ pre-existing environmental values, beliefs, and behavioral norms to inspire action.

Comparisons across Sites

While participants are similar along many demographic and social-psychological variables, they differ on others, suggesting that each facility might be attracting a somewhat different audience. DLC attracts fewer parties with children than the other two facilities, even though NCA is the only facility with age restrictions for their tours (children under five are not allowed). This could be related to DLC’s focus on science and research, which might appear unsuitable for young children. Additionally, DLC participants had visited more environmental/animal facilities in the last two years and have more education on average than NCA visitors. These data combined suggest that DLC may attract people with more knowledge of and motivation to attend animal-themed and environmentally focused programs than traditional zoos and aquariums.

AAS scores tracked along with relative welfare concerns for the species at each facility. The greater the demonstrated welfare concern of the organization, the higher the AAS scores in the audience. CTR visitors scored highest, followed by DLC, and then NCA. In interviews, participants at all three sites indicated that sensitivity to animal conditions drives the decision to attend all of these facilities; these data combined suggest that facilities like CTR where animal welfare is highlighted may be capturing an audience unwilling to attend zoos and aquariums because they have higher baseline sensitivity to animal welfare concerns than average AZA audiences. This could mean that participants select for specific causes as opposed to general environmental interest, supporting the idea of “multidimensional environmentalism” (Ignatow, 2006, p. 443).

In addition to scoring highest on the AAS, CTR visitors also scored lower on the altruistic values scale than NCA visitors. If one considers anthropocentric values to be in contrast to biospheric values (Gagnon Thompson & Barton, 1994; Schultz, 2000), then this result is not surprising. The species at NCA have the highest utilitarian value and the lowest overall charisma of the species housed at the three sites (Czech, Kausman, & Borkhataria, 1998), thus they may attract people for whom anthropocentric/altruistic conservation is the most compelling.

NCA visitors had on average less education and were more politically conservative than audiences at CTR or DLC. Previous research has shown that these groups express less environmental care than more liberal, educated individuals (Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, & Jones, 2000; Nooney et al., 2003). However, NCA visitors expressed a greater sense of personal responsibility for environmental problems than visitors at DLC. This result appeared in the naïve model and became more pronounced when demographic variables were controlled for, suggesting that animal-themed facilities might either attract environmentalists across the political spectrum or activate environmental values that transcend political leanings.

Alternately, the greater sense of personal responsibility among NCA visitors might be best explained by place attachment (Vorkinn & Riese, 2001). In particular, natural place attachment (as opposed to civic place attachment) predicts pro-environmental behavior (Scannell & Gifford, 2017). NCA might activate a natural place-based values system because they focus on the conservation of local species. NCA tour guests have also visited NCA more frequently in the past than guests at CTR or DLC, suggesting that there could be a place attachment to NCA itself.

Comparisons with Other Audiences

Learners at all three sites are more wealthy, educated, and white than both the US population and the average AZA visitor (Khalil & Ardoin, 2011). While NCA is an AZA facility, signing up for a guided program might select for a subset of their general audience who has more time, resources, and personal interest. While educating conservation-literate populations helps advance learning goals, this practice does not help extend conservation messages to historically excluded populations (Brewer, 2001). Animals appear to help diversify audiences in zoo and aquarium contexts, but more effort is needed to bring animals to audiences beyond the walls of the traditional institutions that house them (Nadkarni, 2004).

Sociodemographic variables have had somewhat consistent but weak relationships with environmental concern (Dietz, Stern, & Guagnano, 1998), and regression analysis supports some historical results but not others. Political orientation was the most consistent predictor of VBN characteristics in the expected direction, which echoes deepening partisan divides in environmentalism of the last 30 years (Anderson, 2017). Gender was the next most consistent predictor of environmental VBN, again reflecting existing literature (Davidson & Freudenburg, 1996; Gifford & Nilsson, 2014). However, older participants in my study had significantly higher biospheric values/personal responsibility scores and lower egotistic values scores than younger respondents, which goes against previous research. Interview data support this result; participants described increased awareness of the environment and conviction in their environmental beliefs over time. While previous research has measured both a period and aging effect (Jones & Dunlap, 1992; Klineberg, McKeever, & Rothenbach, 1998; Mohai & Twight, 1987), other research has shown that young peoples’ environmental concern has stagnated since the 1990s (Wray-Lake, Flanagan, & Osgood, 2010), and millennials may exhibit more narcissistic tendencies than previous generations (Bourke, 2010; Twenge, 2006); perhaps these other trends confound the relationship between age and VBN metrics. Longitudinal data is needed to understand how aging and cohort effects determine VBN scores in learner populations.

Wealth has historically been weakly associated with environmental variables, and has been both positively and negatively correlated with environmental concern (Ignatow, 2006). In places with good economic growth, postmaterialist values of wealthier individuals link with environmental concern (Franzen & Vogl, 2013). But there is also evidence that poorer individuals may be more concerned about environmental issues (Gifford & Nilsson, 2014). The wealthiest respondents in my sample had lower environmental VBN scores than the next wealthiest group, but no relationship was observed with lower wealth categories, suggesting the presence of multiple drivers of environmental values related to wealth (Franzen & Meyer, 2009).

Egotistic values have been a somewhat contentious part of VBN theory. Egotistic values can strengthen one’s commitment or weaken it because of sensitivity to external factors (de Groot & Steg, 2007a; Milfont, Sibley, & Duckitt, 2010; Schultz et al., 2005). Some scholars have argued that the divide is between ecocentric and anthropocentric values only, combining altruistic and egotistic values (Milfont & Duckitt, 2004). Other argue the case for the self-transcendent/self-preserving values divide, separating egotistic from biospheric/altruistic values (Miller et al., 2004; Schwartz, 2012; N. Taylor & Signal, 2005). Biospheric values correlated highly with other VBN variables in my survey data, yet neither egotistic nor anthropocentric values were correlated with any other VBN variables or with each other, suggesting that egocentric and altruistic values scales capture two separate dimensions, but neither is particularly strongly associated with environmental VBN. However, interviewees more easily integrated altruistic values into their VBN narratives than they did egotistic values, supporting the case for the importance of self-transcendent values. The lack of clarity in my data could indicate that the dimensionality along these three values orientations is weaker in my sample than has been demonstrated in previous studies (de Groot & Steg, 2008). Or, as including contact information was a significant predictor of environmental VBN, the social undesirability of egocentric statements might have biased these results (Nederhof, 1985).

Profile of the Interviewees

Interviewees stressed the importance of environmental stewardship, an animal’s right to a decent life, a concern for ecological crisis, and the belief in ecological interdependence; these ideas arose in some form during all interviews. Learners at all three sites overwhelmingly support environmental protection. These results reflect the general shift in the U.S. population toward the New Ecological Paradigm for the last 40 years (Dunlap, 2008), and the audiences at zoos and aquariums are even more environmentally conscious than the average American (Falk et al., 2009).

Learners were also pro-environmental across the political spectrum, suggesting that animal-themed facilities may attract more environmentally conscious individuals of all political backgrounds. Every interviewee articulated the need for humankind to treat animals with respect and manage them sustainably. Animal welfare could thus represent fertile ground for crossing political divides to support environmental values, beliefs, and norms. As other environmental topics such as climate change have had a polarizing effect on the US population (Kahan et al., 2012) finding ways for people with otherwise divergent views to support a common cause could help bridge gaps in environmental politics (Proctor et al., 2018; Weber, 2003). In particular, educators could connect conservative Christian values of personal responsibility and frugality with environmentalism (Greenberg, 2006; Pepper, Jackson, & Uzzell, 2011).

Interviewees expressed apprehension about captivity in the zoo and/or aquarium context, suggesting that context matters for animal captivity. This finding goes against previous AZA-sponsored research showing the public does not support critiques of zoos because of captivity concerns (Fraser & Sickler, 2009), so this issue with captivity warrants further attention. More research is needed comparing zoos to aquariums; researchers tend to lump these two types of facilities together (i.e. Miller et al., 2004), yet visitors at all three of my sites expressed apprehension about zoos, but not about aquariums.

Further, applying VBN to visitors in animal-related facilities elucidates how animal welfare attitudes relate to environmental attitudes. While animal welfare and environmental activists have had some philosophical conflict (Callicott, 1988; A. Taylor, 1996), my study did not uncover a conflict between the two. The high correlation between the AAS and NEP combined with my interview data suggest that animal welfare and environmental concerns are heavily intertwined in learner populations. This result suggests that these learner populations may be receptive to messages in which animal welfare and environmental messages are combined under the umbrella of the expansion of moral obligation to animals and their habitats.

The religious theme that emerged has also been identified in the literature as a driving force in environmental beliefs. Fraser and colleagues (2009) interviewed religious leaders and identified religious narratives about nature as God’s creation and the importance of stewardship. NEP research done in North Carolina found that the man-over-nature dimension was unique within the NEP scale because of its religious/hierarchical nature (Nooney et al., 2003). Ignatow (2006) has also argued that spirituality influences the determinants of environmental care. While I did not test for dimensionality in my survey data, interview data suggest that spiritual influences may play a large role in shaping environmental beliefs in audiences in this region. The Christian construct of human dominion over nature may play a critical role in shaping the environmental stewardship ethic in these audiences. Future survey research could collect religion data in addition to the VBN metrics.

Norms and Behavior

Because self-reported behavior is not a perfect measure of environmental behavior (Gatersleben, Steg, & Vlek, 2002), claims must be taken with caution. However, behavioral statements provide insight into behavioral knowledge and norms, two important determinants of behavior (P. C. Stern et al., 1999).

Norms elucidate the cognitive process of behavioral self-assessment. Almost every interviewee labeled their environmental behavior as “pretty good,” regardless of which behaviors they engage in. Norms contain both a psychological and a social process; in the former, the individual internally establishes norms to ensure he/she is not too deviant from the correct behavior, and in the latter, the behaviors and attitudes in one’s community shape how one defines norms (Turaga, Howarth, & Borsuk, 2010). In my sample, those who engaged in advanced types of pro-environmental behavior saw themselves as similarly good about environmental behavior as those who only recycle. This tendency to focus on recycling and other waste management behaviors has been observed elsewhere (Gould, Ardoin, Biggar, Cravens, & Wojcik, 2016), and this represents a real barrier to more effective environmental behaviors. Because norms are such a powerful determinant of behavior (Goldstein, Cialdini, & Griskevicius, 2008), educators at all three sites could consider how to use their knowledge of behavioral norms within their visitor populations to push participants toward more effective conservation behavior.

Conclusion

My data suggest that individuals choose to attend interpretive programs where the mission and activities of the organization reinforce their existing values, beliefs, and norms. Most notably, specialty organizations may be capturing audiences that are opting out of more traditional animal-themed programming, meaning that these organizations have a unique opportunity to deliver environmentally themed messaging to animal-sensitive populations. With a better understanding of their unique audience, educators can establish behavioral norms that activate visitors’ existing VBN, perhaps leading to a higher likelihood of adopting additional pro-environmental behaviors.

Even though political orientation was predictive of environmental VBN in the expected ways, conservative learners also valued environmental care and animal welfare. While this research cannot obviate the need for data collected at individual institutions, my findings indicate that interpreters could be more forthcoming with behavioral recommendations related to animal welfare and conservation than they would be with more controversial topics such as climate change.

Zoo and aquarium education research represents a relatively disparate, diffuse field of inquiry (Ogden & Heimlich, 2009). By bringing diverse types of animal-themed facilities into the conversation, I have entered territory with even less cohesion in terms of both research and practice. More work is needed to characterize and evaluate the landscape of animal-themed education across different types of organizations so that we can better understand how diverse organizations serve diverse audience needs and facilitate the adoption of pro-environmental behavior. In the meantime, interpretive professionals can consider the relationship between their own audiences and those in this study to assess whether ideas like animal welfare sensitivity, place attachment, political orientation, religiosity, or any of the VBN variables may be a key consideration in program development at their site.

Acknowledgements

I thank my dissertation committee and my research participants for their time and thoughts. I also thank Ashton Verdery for help with my statistics.

References

Allison, P. (2012). When can you safely ignore multicollinearity? Retrieved from

http://www.statisticalhorizons.com/multicollinearity

Anderson, M. (2017). For Earth Day, here’s how Americans view environmental issues. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/20/for-earth-day-heres-how-americans-view-environmental-issues/

Archer, D., & Wearing, S. (2003). Self, Space, and Interpretive Experience: The Interactionism of Environmental Interpretation. Journal of Interpretation Research, 8(1).

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Hughes, K. (2008). Environmental awareness, interests and motives of botanic gardens visitors: Implications for interpretive practice. Tourism Management, 29(3), 439–444. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.05.006

Bourke, B. (2010). A New Me Generation? The Increasing Self-Interest Among Millennial College Students. Journal of College and Character, 11(2).

Brewer, C. (2001). Cultivating conservation literacy: “trickle-down” education is not enough. Conservation Biology, 1203–1205.

Brochu, L., & Merriman, T. (2015). Personal Interpretation: connecting your audience to heritage resources. InterpPress.

Burgess, J., Limb, M., & Harrison, C. M. (1988). Exploring environmental values through the medium of small groups. 1. Theory and practice. Environment and Planning A, 20(3), 309–326. doi:10.1068/a200309

Caplow, S. (2014). The Communication of Values, Beliefs, and Norms in Live Animal Interpretive Experiences: A Comparative Case Study. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

Caplow, S. (2018). The presentation of environmental values, beliefs, and norms in live animal interpretive experiences. Environmental Education Research, 1–16.

Callicott, J. B. (1988). Animal liberation and environmental ethics: back together again. Between the Species, 4(3), 3.

Chawla, L., & Cushing, D. F. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 437–452.

Clayton, S., Fraser, J., & Saunders, C. D. (2009). Zoo Experiences: Conservation, Connections, and Concern for Animals. Zoo Biology, 28, 377–397.

Clayton, S., & Myers, G. (2009). Conservation Psychology: Understanding and promoting human care for nature. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2007). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

CTR. (2012). Carolina Tiger Rescue - Home Page. Retrieved from

www.carolinatigerrescue.org

Czech, B., Kausman, P. R., & Borkhataria, R. (1998). Social construction, political power, and the allocation of benefits to endangered species. Conservation Biology, 12(5), 1103–1112.

Davidson, D. J., & Freudenburg, W. R. (1996). Gender and environmental risk concerns: A review and analysis of available research. Environment and Behavior, 28(3), 302–339.

de Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2007a). Value Orientations and Environmental Beliefs in Five Countries: Validity of an Instrument to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(3), 318–332. doi:10.1177/0022022107300278

de Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2007b). Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior: How to Measure Egotistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40(3).

de Groot, J. I. M., & Steg, L. (2008). Value Orientation to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior: How to Measure Egotistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Environment and Behavior, 40(3), 330–354.

Dierking, L., Burtnyk, M. S., Buchner, K. S., & Falk, J. (2002). Visitor Learning in Zoos and Aquariums: A Literature Review. Institute for Learning Innovation, Annapolis, MD.

Dietz, T., Stern, P. C., & Guagnano, G. A. (1998). Social structural and social psychological bases of environmental concern. Environment and Behavior, 30(4), 450–471.

DLC. (2012). About the Duke Lemur Center. Retrieved from http://lemur.duke.edu/about-the-duke-lemur-center/

Dunlap, R. E. (2008). The new environmental paradigm scale: From marginality to worldwide use. The Journal of Environmental Education, 40(1), 3–18.

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Mertig, A. G., & Jones, R. E. (2000). Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 425–442. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00176

Ellenbogen, K. M. (2003). From dioramas to the dinner table: An ethnographic case study of the role of science museums in family life.

Falk, J. (2005). Free-choice environmental learning: framing the discussion. Environmental Education Research, 11(3), 265–280.

Falk, J., & Adelman, L. M. (2003). Investigating the Impact of Prior Knowledge and Interest on Aquarium Visitor Learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40(2), 163–176.

Falk, J., & Dierking, L. (2002). Lessons without limit: How free-choice learning is transforming education. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

Falk, J., Heimlich, J. E., & Foutz, S. (2009). Free-choice learning and the environment. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

Falk, J., & Storksdieck, M. (2010). Science Learning in a Leisure Setting. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47(2), 194–212. doi:10.1002/tea.20319

Falk, J., Storksdieck, M., & Dierking, L. (2007). Investigating public science interest and understanding: evidence for the importance of free-choice learning. Public Understanding of Science, 16(4), 455–469. doi:10.1177/0963662506064240

Franzen, A., & Meyer, R. (2009). Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. European sociological review, 26(2), 219–234.

Franzen, A., & Vogl, D. (2013). Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries. Global Environmental Change, 23(5), 1001–1008.

Fraser, J., & Sickler, J. (2009). Why Zoos and Aquariums Matter Handbook: Handbook of Research, Key Findings and Results from National Audience Survey. Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

Gagnon Thompson, S. C., & Barton, M. A. (1994). Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 14(2), 149–157.

Gatersleben, B., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2002). Measurement and Determinants of Environmentally Significant Consumer Behavior. Environment and Behavior, 34(3), 335–362. doi:10.1177/0013916502034003004

Gifford, R., & Nilsson, A. (2014). Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. International Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 141–157.

Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 472–482.

Gould, R. K., Ardoin, N. M., Biggar, M., Cravens, A. E., & Wojcik, D. (2016). Environmental behavior’s dirty secret: The prevalence of waste management in discussions of environmental concern and action. Environmental Management, 58(2), 268–282.

Greenberg, N. (2006). Shop right: American conservatisms, consumption, and the environment. Global Environmental Politics, 6(2), 85–111.

Hart, P. & Nolan, K. (1999) A Critical Analysis of Research in Environmental Education. Studies in Science Education, 34, 1–69.

Hawcroft, L. J., & Milfont, T. L. (2010). The use (and abuse) of the new environmental paradigm scale over the last 30 years: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(2), 143–158. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.10.003

Herzog, H. A., Betchart, N. S., & Pittman, R. (1991). Gender, sex role identity and attitudes towards animals. Anthrozoos, 4, 184–191.

Herzog, H. A., & Golden, L. L. (2009). Moral Emotions and Social Activism: The Case of Animal Rights. Journal of Social Issues, 65(3), 485–498.

Hungerford, H. R., & Volk, T. L. (1990). Changing learner behavior through environmental education. Journal of Environmental Education, 21(3), 8–21.

Hutchins, M., Smith, B., & Allard, R. (2003). In defense of zoos and aquariums: the ethical basis for keeping wild animals in captivity. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 223(7), 958–966.

Ignatow, G. (2006). Cultural models of nature and society: Reconsidering environmental attitudes and concern. Environment and Behavior, 38(4), 441–461.

Jacobson, S. K., McDuff, M. D., & Monroe, M. C. (2006). Conservation education and outreach techniques. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Jones, R. E., & Dunlap, R. E. (1992). The Social Bases of Environmental Concern: Have They Changed Over Time? Rural Sociology, 57(1), 28–47. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.1992.tb00455.x

Kaiser, F. G. (1998). A general measure of ecological behavior. Journal of applied social psychology, 28(5), 395–422.

Kahan, D. M., Peters, E., Wittlin, M., Slovic, P., Ouellette, L. L., Braman, D., & Mandel, G. (2012). The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nature Climate Change, 2(10), 732–735.

Khalil, K., & Ardoin, N. (2011). Programmatic Evaluation in Association of Zoos and Aquariums—Accredited Zoos and Aquariums: A Literature Review. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 10(3), 168–177.

Kim, A. K., Airey, D., & Szivas, E. (2011). The multiple assessment of interpretation effectiveness: Promoting visitors’ environmental attitudes and behavior. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 321–334.

Klineberg, S. L., McKeever, M., & Rothenbach, B. (1998). Demographic predictors of environmental concern: It does make a difference how it’s measured. Social Science Quarterly, 734–753.

Knapp, D., & Benton, G. M. (2004). Elements to Successful Interpretation: A Multiple Case Study of Five National Parks. Journal of Interpretation Research, 9(2).

Knight, S., & Herzog, H. (2009). All Creatures Great and Small: New Perspectives on Psychology and Human–Animal Interactions. Journal of Social Issues, 65(3), 451–461. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01608.x

Lofland, J. (2006). Analyzing social settings : a guide to qualitative observation and analysis. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd. ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Milfont, T. L., & Duckitt, J. (2004). The structure of environmental attitudes: A first- and second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(3), 289–303.

Milfont, T. L., Sibley, C. G., & Duckitt, J. (2010). Testing the Moderating Role of Components of Norm Activation on the Relationship Between Values and Environmental Behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41, 124–131.

Miller, B., Conway, W., Reading, R. P., Wemmer, C., Wildt, D., Kleiman, D., & Hutchins, M. (2004). Evaluating the conservation mission of zoos, aquariums, botanical gardens, and natural history museums. Conservation Biology, 18(1), 86–93. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00181.x

Mohai, P., & Twight, B. W. (1987). Age and environmentalism: An elaboration of the Buttel model using national survey evidence. Social Science Quarterly, 68(4), 798.

Nadkarni, N. M. (2004). Not preaching to the choir: Communicating the importance of forest conservation to nontraditional audiences. Conservation Biology, 18(3), 602–606.

National Park Service, 2002. How Interpretation Works: The Interpretive Equation. Retrieved from https://www.nps.gov/idp/interp/101/howitworks.htm.

NCA. (2012). North Carolina Aquariums. Retrieved from http://www.ncaquariums.com

Nederhof, A. J. (1985). Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15(3), 263-280. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420150303

Nooney, J. G., Woodrum, E., Hoban, T. J., & Clifford, W. B. (2003). Environmental Worldview and Behavior: Consequences of Dimensionality in a Survey of North Carolinians. Environment and Behavior, 35(6), 763-783. doi:10.1177/0013916503256246

Nordlund, A. M., & Garvill, J. (2002). Value structures behind proenvironmental behavior. Environment and behavior, 34(6), 740–756.

Noss, A. (2014). Household income: 2013. United States Census Bureau, US Department of Commerce, 12(2).

Nunnaly, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ogden, J., & Heimlich, J. E. (2009). Why Focus on Zoo and Aquarium Education? Zoo Biology, 28(5), 357–360. doi:10.1002/zoo.20271

Patrick, P. G., & Caplow, S. (2018). Identifying the foci of mission statements of the zoo and aquarium community. Museum Management and Curatorship, 33(2), 120–135.

Patrick, P. G., Matthews, C. E., Ayers, D. F., & Tunnicliffe, S. D. (2007). Conservation and Education: Prominent Themes in Zoo Mission Statement. Journal of Environmental Education, 38(3), 53–59.

Pepper, M., Jackson, T., & Uzzell, D. (2011). An examination of Christianity and socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 43(2), 274–290.

Proctor, J. D., Bernstein, J., Brick, P., Brush, E., Caplow, S., & Foster, K. (2018). Environmental engagement in troubled times: a manifesto. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 1–6.

Rickinson, M. (2001). Learners and Learning in Environmental Education: a critical review of the evidence. Environmental Education Research, 7(3), 207–320.

Ryan, C. L., & Bauman, K. (2016). Educational attainment in the United States: 2015.

Saldana, J. (2009). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage.

Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2017). Place attachment enhances psychological need satisfaction. Environment and Behavior, 49(4), 359–389.

Schultz, P. W. (2000). New Environmental Theories: Empathizing With Nature: The Effects of Perspective Taking on Concern for Environmental Issues. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 391–406.

Schultz, P. W., & Tabanico, J. J. (2007). Self, Identity, and the Natural Environment: Exploring Implicit Connections With Nature1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37(6), 1219–1247.

Schultz, P. W., Valdiney, V., Gouveia, L. D., Cameron, G. T., Schmuck, P., & Franek, M. (2005). Values and their Relationship to Environmental Concern and Conservation Behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 457–475.

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1).

Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of environmental psychology, 29(3), 309-317.

Stern, M., & Powell, R. (2013). What leads to better visitor outcomes in live interpretation? Journal of Interpretation Research, 18(2).

Stern, M., Powell, R., Martin, E., & McLean, K. (2012). Identifying best practices for live interpretive programs in the United States National Park Service.

Stern, P. C. (2000). New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 407–424. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00175

Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Human Ecology Review, 6(2), 81–96.

Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., & Guagnano, G. A. (1995). The New Ecological Paradigm in Social-Psychological Context. Environment and Behavior, 27(6), 723–743.

Storksdieck, M., Ellenbogen, K., & Heimlich, J. (2005). Changing minds? Reassessing outcomes in freechoice environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 11(3), 353–369.

Taylor, A. (1996). Animal rights and human needs. Environmental Ethics, 18(3), 249–264.

Taylor, N., & Signal, T. D. (2005). Empathy and attitudes to animals. Anthrozoos, 18, 18–27.

Turaga, R. M. R., Howarth, R. B., & Borsuk, M. E. (2010). Pro-environmental behavior: Rational choice meets moral motivation. Ecological Economics Review, 1185, 211–224.

Twenge, J. M. (2006). Generation me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled—and more miserable than ever before. Simon and Schuster.

Vorkinn, M., & Riese, H. (2001). Environmental concern in a local context: The significance of place attachment. Environment and Behavior, 33(2), 249–263.

Weber, E. P. (2003). Bringing society back in: Grassroots ecosystem management, accountability, and sustainable communities. MIT Press.

Wray-Lake, L., Flanagan, C. A., & Osgood, D. W. (2010). Examining trends in adolescent environmental attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors across three decades. Environment and Behavior, 42(1), 61–85.

Young, A., Khalil, K. A., & Wharton, J. (2018). Empathy for Animals: A Review of the Existing Literature. Curator: The Museum Journal, 61(2), 327–343.