Journal of Interpretation Research

Volume 23, Number 2

Increasing Visitor Engagement During Interpretive Walking Tours

David Douglas

Church Educational System

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Gary Ellis

Texas A&M University

Andrew Lacanienta

California Polytechnic State University

1 Grand Avenue

San Luis Obispo, CA 93407-9000

alacanie@calpoly.edu

Abstract

This study examined the effect of living-history interpretation (i.e., first-person, third-person, no living history) and question type (i.e., relevant, dissonant, customary) on engagement of visitors during walking tours at a heritage site. One hundred seventy-six visitors participated in the study. Visitors completed a measure of engagement immediately following each of six stops during the walking tour. A measure of guest familiarity of the context of the site was also taken. Results from linear mixed-modeling revealed a three-factor interaction effect, familiarity by question type by living-history interpretation. Engagement of visitors is impacted by guest familiarity with the context, the living-history interpretation type, and the question type posed. Results might guide interpretation professionals in customizing interpretation experiences to stage more engaging interpretation experiences.

Keywords

engagement, familiarity, dissonance, heritage interpretation, living history, provocation, question type, theory of structured experience

Increasing Engagement During Heritage Interpretation Talks

Engagement is pivotal to the overall quality of visitor experiences at heritage sites (e.g., Beck & Cable, 1998; Moscardo, 1996, 1999; Sutcliffe & Kim, 2014; Tilden, 1977). Engagement, a motivational state of focused involvement in learning, has been associated with numerous benefits. Among these are increased attention, active participation, enjoyment, enthusiasm, and lack of anxiety (Reeve, 2012). Researchers have found that greater levels of engagement promote curiosity, exploration, discovery, and ultimately greater levels of learning and satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, 2002; Ellis, Freeman, Jamal, & Jiang, 2017; Moscardo, 1999). Interestingly though, engagement is one of the least researched aspects of active participation (Fredricks, Bohnert, & Burdette, 2014).

Interpreters use a variety of strategies to promote engagement. One of these strategies is using props and cues inherent to the site. Props and cues advance a pervasive theme (Lacanienta, Ellis, Taggart, Wilder, & Carroll, 2018; Pine & Gilmore, 2011) and elevate visitors’ engagement in the story. Compared to a tour with a guide in contemporary clothing and modern idiom, a tour with a guide in period costume and period idiom provides added novelty, coherence, and richness to the experience (Pine & Gilmore, 2011). Coherent themes allow for a more focused processing of information (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan & Talbot, 1983).

Interpreters must also attend to how they tell the story. One strategy is by using provocative questions (Ham, 1992; King, 2002; Tilden, 1977). Little research attention has been paid to what kinds of questions stimulate visitor engagement in an interpretive story. Tilden’s (1977) legendary grounded inquiry into interpretation yielded the principle that any interpretation failing to connect the story to something within the visitor will be “sterile” (p. 9). Questions encouraging visitors to make an interpretive scene relevant to their own lives may be more engaging. Such questions seek to connect a current personal interest with an occurrence that might have also been a pressing issue in the event being interpreted. Thus, the visitor gains an empathetic and engaging sense of what one aspect of life might have been like.

Although the above reasoning provides warrant for the argument that a connection exists between living-history interpretation type, question type, and visitor engagement with interpretive tours, such evidence should not be taken as certainty. Distractions exist that may weaken the effects of these techniques. Environmental distractions, such as weather or crying children, may distract from the tour and decrease engagement. Unenthusiastic interpreters lacking animation and voice inflection can also inhibit the quality of interpretive experiences. Further, the structured use of questions in interpretive settings may not increase visitor engagement. Although such questioning techniques have demonstrated to be impactful in classroom settings (e.g., King, 2002) they may not be effective in heritage tourism settings. It is important to know how living-history interpretation type, question type, and familiarity are related to levels of engagement in heritage tours. This study examined the effect of living-history interpretation type (i.e., first-person, third-person, none), question type (i.e., relevant, dissonant, customary), and familiarity with the context of the site being interpreted on visitor engagement during a walking tour at a heritage site.

Literature Review

Engagement

The idea of engagement was constructed from the foundation of the idea of mindfulness (Langer, 2000). The resulting measure was consistent with contemporary approaches to measuring engagement in that its elements embraced cognitive, behavioral, and emotional engagement (Fredricks, Bohnert, & Burdette, 2014; Reeve, 2012). The mindfulness foundation is a departure from traditional information-processing psychology. Cognitive psychologists have noted that, unless motivated otherwise, humans are cognitive misers (Dunn & Risko, 2016; Kaplan, 1995; Langer, 2000). Rather than maximizing rewards through full and effortful information processing, humans frequently use heuristics to cut down on the effort needed to process information. In one approach to describing this process of using heuristics, Langer proposed that people often use scripts to perform familiar tasks. In doing so, they perform tasks by running the script without much thought in a way that might be described as mindless (Langer, 2014).

A second group of psychologists proposed cognitive misering is performed through what they termed environmental cognitive sets (Duvall, 2013; Leff, Gordon, & Ferguson, 1974). Such sets are ways of perceiving one’s surroundings based on specific types of processed information that form an integrated collective set. Applying such a set to a place allows people to make sense of their surroundings with little effort. Subsequent work has led to conceptualization of cognitive misering as: (1) searching for cognitive simplicity rather than utilizing complex cognitive strategies; (2) seeking a single explanation for an event rather than to look for multiple causes and; (3) rejecting the opportunity to consider more information when given the opportunity.

Taking the elements of scripts, cognitive sets, and minimal information processing, Langer (2014) formed the Mindfulness-Mindlessness (M-M) theory suggesting much of what people do in everyday settings is processed mindlessly. She defined mindlessness as:

Behavior that is over-determined by the past … when mindless, one relies on categories and distinctions derived in the past. Mindlessness is single-minded reliance on information without an active awareness of alternative perspectives or alternative uses to which the information could be put. When mindless, the individual relies on structures that have been appropriated from another source (Langer, Hatem, Joss, & Howell 1989, p. 140).

Conversely, mindfulness is described as:

A state of mind that results from drawing novel distinctions, examining information from new perspectives, and being sensitive to context. When we are mindful, we recognize that there is not a single optimal perspective, but many possible perspectives on the same situation (Langer, 1993, p. 44).

Mindfulness, or total focus on the present moment, is characteristic of such heightened states of experience as flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1992), ecstasy (Maslow, 1962), deep play (Ackerman, 2011), and deep structured experience (Ellis et al., 2017).

Mindfulness has also been described as “a mode of functioning through which the individual actively engages in reconstructing the environment through creating new categories or distinctions, thus directing attention to new contextual cues that may be consciously controlled” (Alexander, Langer, Newman, Chandler, & Davies, 1989, p. 951). People who are mindful actively process information. They think and question the world before them. The process of drawing novel distinctions can lead to increased sensitivity to one’s environment, increased openness to new information, the creation of new categories for constructing perception, and an increased awareness of multiple perspectives in problem solving.

Mindfulness is particularly appropriate for examining engagement (Langer, 2009). Mindfulness is used to explain human reactions to interpretation and museum experiences by a variety of scholars (Ablett & Dyer, 2009; Frauman, 2010; Kang & Getzel, 2012; Moscardo, 2009, 2014, 2017). Interpretation encourages more complex thought related to elaboration, mindfulness, and engagement (Ballantyne, Packer, & Falk, 2011; Moscardo, 2014; Walker & Moscardo, 2014). Consequently, learning increases and changes to behavior and attitude may take place.

Engagement is a motivational phenomenon. Motivation energizes and shapes human behavior (e.g., Reeve, 2014). Humans are motivated to engage in tasks or enterprises that give them opportunities to fulfill needs or goals. In this vein, motivation is a complex construct that has three components. The first component of motivation reflects actions and time spent on task. The second is an emotional component wherein engagement (i.e., interest, curiosity, and enjoyment) is manifest in the activity. The third component is orientation, where beliefs about opportunities resulting from activities affect our experience of the activity. Engagement is thus a state of motivation containing elements of interest, curiosity, and enjoyment (Reeve, 2012; 2014). Engagement yields a deep and focused experience in an interpretive activity.

Living-History Interpretation

Living-history interpretation provides a staged experience and immediate engagement into the past. Living-history interpretation is “the re-creation of specific periods of the past or specific events utilizing living interpreters usually clothed and equipped with the correct tools and accouterments of a depicted era” (Luzader & Spellman, 1996, p. 241). Two approaches to living-history interpretation are widely used, first-person living history and third-person living history.

First-person living history.

During first-person living history, interpreters assume the role of an actual person and speak and act in character. They do not recognize future time periods beyond that which they are representing and they refuse to acknowledge visitors are from the present day. First-person interpretation attempts to create a sense of time travel to a different time, place, and set of circumstances.

First-person living history resembles a theatrical or staged production.

Audiences are invited to suspend disbelief to help create the illusion. If the interpreter breaks out of character, coherence is lost and the illusion ends. First-person interpretation has the advantage of involving the visitor and communicating the essence of the era quickly to those who have the imagination to immerse themselves in the experience. Carrying out first-person interpretation requires considerable skill, knowledge, and improvisation ability (Hunt, 2004). The success of first-person interpretation depends to a great extent on the ability of the interpreter to get into and stay in character. First-person interpreters must conform to characters emotionally, physically, and intellectually. In other words, an actor must become the character (Pine & Gilmore, 2011).

Third-person living history.

During third-person living history the interpreter may use period dress and idiom but moves freely in and out of time periods. An interpreter might, for example, appear in period dress, but will interact with the guests according to his or her role as the interpreter of the 21st-century heritage site. The third-person approach enables a rich experience for visitors who enjoy making comparisons between the interpreted worlds and their own experiences. Third-person interpretation may help to understand the contrast between present and past conditions. Third-person living history tends to lead to more complex conversations with visitors because visitors need to adjust their understanding of the role-playing component and may experience confusion with a guide switching in and out of time periods.

The degree of confusion present might also be related to the visitors’ degree of familiarity with the context of the interpretive site. Visitors who have lower levels of knowledge may experience greater engagement from the increased engagement and theatrics of first-person interpretation, while those with greater knowledge might enjoy third-person interpretation for its depth facilitated by comparison between the interpretive modern experiences.

Question Types

One popular strategy in contemporary educational psychology concerns the use of questioning types (King, 2002). Questions that introduce uncertainty and require thoughtful processing may increase engagement. Questions that are relevant or create dissonance may also create curiosity and arousal and help visitors to make personal connections. One educational questioning strategy employs an arousal type teaching technique called conditional or ambiguous instruction. Rather than teaching concepts with absolute certainty, instructors use language that promotes more cognitive processing (Bruin, Meppelink, & Bogels, 2015; Ritchart & Perkins 2000). Ambiguous situations promote increased engagement because they demand cognition. The individual becomes engaged by striving to make sense of the situation. Such situations can be created through both relevance and dissonance questions.

Relevance questions.

One of Tilden’s (1977) principles of interpretation is, “Interpretation that does not relate what is being displayed or described to something with the personality or experience of the visitor will be sterile” (p. 9). Relevance suggests the importance of connecting the subject matter to the visitors’ personal lives. Some examples of relevance questions in a pioneer heritage setting follow:

- Have you ever had a time in your life where you wondered if you would make it, like the pioneers we are discussing?

- Do you know anyone who (like the character being interpreted) is a rough and tough character but incredibly loyal or dedicated to a cause?

- For some pioneers the journey was too hard and they turned back. Have you ever taken on something that was so hard that you wanted to quit or turn back?

For many years, educators have employed a relevance questioning technique called apperception. Apperception is the process through which new experiences are understood through connection to previous experiences. If interpreters have something difficult to explain, they might first begin with something the visitor already knows. Then make a comparison with new information. The process of making such comparisons and drawing relevant inference from times past or unfamiliar situations can be highly engaging.

Dissonance questions.

The theory of cognitive dissonance provides a basis for asking dissonance questions to elicit engagement (Festinger, 1957). Cognitive dissonance is a tension people feel when there is inconsistency between thoughts and behaviors. People find inconsistencies uncomfortable and are motivated to maintain consistency among their cognitions. When people feel dissonance, it often occurs when two simultaneously accessible thoughts or beliefs are inconsistent. Festinger argued that to reduce this unpleasant condition, people become aroused while struggling to adjust their thinking. Such arousal is highly engaging and is a motivational force causing one to reduce the unpleasant arousal. Some examples of dissonance questions in a pioneer heritage setting follow:

- What crimes do you believe are bad enough that they are worthy of death?

- What concerns would you have in trusting a man who has served time in jail for attempted murder?

- If your religious leader you deeply respected instructed you to practice plural marriage, how do you believe you would respond?

Not all dissonant situations are uncomfortable. Optimal arousal theory (Ellis, 1973) suggests individuals may crave dissonance for its excitement. As such, interpretive tours including dissonance questions can be expected to yield high levels of engagement.

The Theory of Structured Experiences

Recent literature related to interpretation experiences provides substantive evidence for the previously proposed relationships. The Theory of Structured Experience (TSE; Ellis et al., 2017) outlines three types of experiences: immersion, absorption, and engagement. Of particular interest to this study is the notion of an engagement experience defined as “a transitory condition of heightened attention, emotion, and motivation characterized by (a) extraordinarily high focus of attention on an unfolding narrative or story told in words, actions, and/or music, (b) heightened emotions, and (c) agentic inclinations” (Ellis et al., 2017, p. 7). Narrative has been defined as a recounting of events organized in a sequence resulting in a story (Kim, 2016). Engagement experiences also involve a story as is ordinarily the case in interpretive talks.

Ellis et al. (2017) outlined propositions specific to engagement experiences within the TSE: (1) as provocation increases, engagement tends to increase, (2) as story coherence increases, engagement tends to increase, (3) as personal relevance of the story increases, engagement tends to increase, (4) as mindfulness on the story increases, engagement tends to increase (Ellis et al., 2017; Reeve, 2012; Tilden, 1977). These propositions align well with the reviewed literature and suggest that the effect of living-history interpretation type (i.e., first- or third-person) and question type (i.e., relevant or dissonant) on visitor engagement may be solidly founded in the theory.

Visitors who have differing levels of familiarity with the subject matter may also respond differently to question types and varying types of living-history interpretation. Perhaps, for example, visitors with greater levels of familiarity may prefer frank discussions with interpreters about relatively complex facets of the narrative rather than working through the theatrics of first-person living-history interpretation. Third-person interpretation or no living-history interpretation may thus be more effective for guests who have a high level of familiarity. Those forms of interpretation may allow for a certain depth of knowledge to be shared without too much acting. Conversely, visitors with lower levels of familiarity may prefer the novelty of the theatrical performance of an interpreter engaged in first-person living-history interpretation. Therefore, we hypothesized that an interaction effect exists among living-history interpretation type, question type, and guests’ familiarity with the context of the site.

Method

Data were collected during interpreter-led walking tours at the Old Deseret Village at This is The Place Heritage Park during the months of April–August, 2006. This is the Place Heritage Park is a living-history attraction that presents the story of everyday life in a typical Utah settlement during 1847–1897. The landscape is composed of more than 40 re-created and original buildings from settlements throughout Utah. Costumed interpreters demonstrate life as it would have been for 19th-century Utahans. During special event days, interpreters portraying several of Utah’s most prominent citizens of the period, including Brigham Young, Mary Fielding Smith, and Orrin Porter Rockwell, can be seen walking the streets of the Village.

Orrin Porter Rockwell was the character depicted in the living-history tours. Rockwell was a famous and colorful Mormon lawman, bodyguard for Mormon leaders, and scout in the Utah territory. He has been described as a pioneer-day Samson, destroying angel, and a tough man with a loyal heart, an iron will and an excellent aim (Dewey, 1986). Rockwell was a gunfighter, religious enforcer, and United States Marshal (Hollister, 1886).

Participants

The sample included 176 adult visitors. The average age of participants was 39.7 years (SD=14.19), and 55% were female. The average party size for the tours was 10.15 (SD=11.38). Data were collected only from adult participants, age 18 or older.

Measurement

Engagement was conceptualized as consisting of elements of behavior, emotion, and cognition (Fredricks, Bohnert, & Burdette, 2014), and was measured using an adaptation of Moscardo’s mindfulness scale (Frauman, 1999). Sample items included, “my curiosity is aroused,” and “my interest has been captured.” Consistent with the emotional component of Reeve’s (2012) conceptualization of emotional engagement the questionnaire included items measuring enjoyment and lack of anxiety. Scores were summed across responses to nine items, with response categories ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 9 (very strongly agree). Reliability estimates for the nine-item scale ranged from .95 to .96 across responses to six interpretive talks.

Familiarity was measured using a behavior-anchored rating scale (e.g., Jones & George, 2006) and measured visitors’ knowledge of Later-Day Saint (LDS) history. Participants were asked to rate themselves from 0 to 100 on their familiarity with LDS history. To assist them in their rating, they were directed to count the numbers of books about LDS history that they had read, the number of classes on LDS history they had taken and number of LDS Church history sites they had visited. Following those counts, visitors recorded a response on a single continuum, ranging from none (scored “0”) to “10 times or more” (Scored 100). Sample responses ranged from 0 (one participant) to 100 (five participants). The mean self-reported familiarity was 57.68 (SD=26.34).

Procedures

Through personal invitations and a poster conspicuously displayed at the entrance to the park, visitors were invited to participate in a 45-minute walking tour of the Old Deseret Village. Tours took place May through September of 2006. The tour was titled, “Porter Rockwell’s Guided Tour of Old Deseret.” One interpreter, who was not blind to the hypotheses and who is an authority on Latter-Day Saint history was used for the entire data collection period.

After an initial greeting, the interpreter presented himself to visitors in one of three roles. In the “first-person living history” role, he introduced himself, in character and in period dress, as Orrin Porter Rockwell. In the “third-person living history” role, the interpreter dressed as Orrin Porter Rockwell, but introduced himself and conducted the tour from his own perspective as a contemporary authority on Latter-Day Saint history (e.g., “Porter Rockwell would have dressed in clothing much like what I am wearing”). In the “no living history” condition, the interpreter did not use period dress and conducted the tour from his perspective as a contemporary authority on Latter-Day Saint history.

After introducing himself, the interpreter informed visitors that (1) they could participate fully in the study by participating in the tour and completing a questionnaire; (2) they could choose to participate in the tour, but not complete the questionnaires; or (3) they could choose to have no involvement in the study whatsoever. Participants were then given a questionnaire booklet and a pencil and were asked to complete a measure of visitors’ degrees of prior experience with Latter-Day Saint history. Subsequently, visitors were asked to respond to each of a series of six duplicate copies of the nine-item engagement scale. These sheets were completed following an interpretive talk at each of six stops on the walking tour. At each stop, visitors listened to a three- to five-minute interpretive talk. At the conclusion of each talk, the interpreter posed one of three types of questions: a relevance question; a dissonance question; or a customary question (i.e., do you have any questions?). Following any brief discussion that occurred, visitors completed the nine-item measure of their engagement at that stop on the tour. At the end of the tour, visitors completed measures of satisfaction, learning, and the interpreter’s behavior.

Design and Manipulation of Study Variables

A two-factor design was used, with living-history interpretation type as the between-subjects factor and question type as the within-subjects factor. The between-subjects variable was living history. That variable had three levels: (1) first-person living history, (2) third-person living history, and (3) no living history. The question type variable was manipulated during the interpretive walking tours. Immediately after completing a three- to five-minute interpretive talk at each of the six stops on the walking tour, the interpreter either posed a question designed to evoke a search for personal relevance among the guests (relevance), a question that was designed to create dissonance within the guests (dissonance), or he simply asked, “Does anyone have a question?” (customary). At one stop, for example, the interpreter recounted a story in which Native Americans attempted to sell two children captured from a warring tribe to Mormon pioneers. When the pioneers refused to purchase the slaves, the Native Americans promptly killed one of the children. Relevance and dissonance questions associated with that interpretive story were as follows:

- Dissonance Question: How do you think the pioneers should have dealt with people offering to sell stolen kids as slaves?

- Relevance Question: Have you ever had something stolen or know someone who has been robbed? How did you feel and what went through you mind?

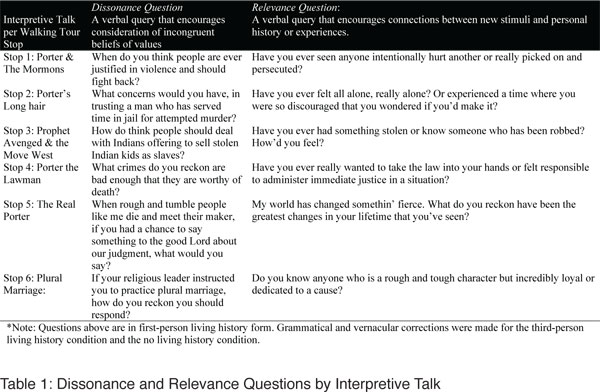

Table 1 provides a summary of the dissonance and relevance questions that were posed following the talk at each of the six stops on the tour.

Following a random start, the relevance and dissonance questions were presented in an alternating pattern. “Pattern A” began with a relevance question and then alternated with dissonance questions for the remainder of the stops on the tour. “Pattern B” began with a dissonance question, and then alternated with relevance questions for the remainder of the tour. “Pattern C” was the condition in which the interpreter simply ended each talk with the query, “does anyone have a question?” The purpose of alternating provoking dissonance type questions with more comfortable relevance questions was to keep the overall tone of the walking tour pleasant and not overly serious in nature.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed through linear mixed modeling procedures (Maxwell & Delaney, 2004; Raudenbush & Bryke, 2002; West, Welch, & Galecki, 2007). The unit of analysis was the individual experience, within visitors. This approach involves restricted maximum likelihood estimation of fixed effects (question type, living-history type, familiarity, and their interactions) and random effects (individual differences among participants) in a multi-level model. Mixed modeling procedures provide a number of important advantages over traditional least squares analysis of variance procedures. Among the more notable of these is the ability to account for violation of the assumption of compound symmetry in the covariance matrix of observations taken at successive points in time.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

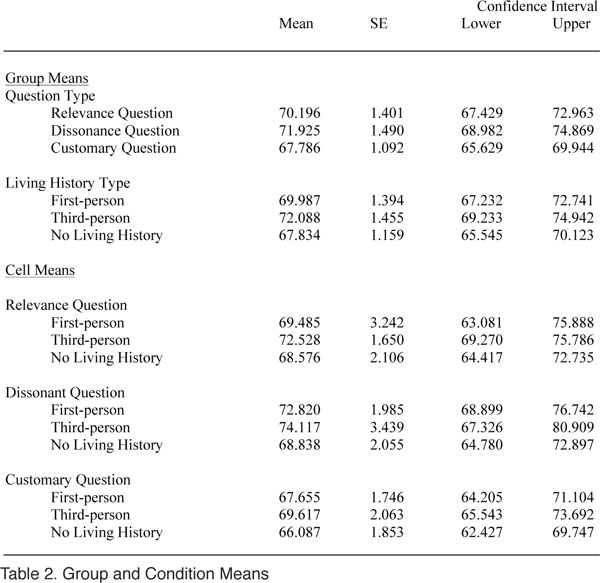

Descriptive statistics for each of the variables are presented in Table 2.

Descriptive statistics revealed that the dissonance questions produced the highest engagement scores in the sample data (M = 70.67, SD = 9.30), followed by relevance questions (M = 70.12, SD = 10.15), and no questions (M = 67.06, SD = 12.31). For the living-history conditions, the mean for third-person living history produced the highest engagement score (M = 71.22, SD = 9.77), followed by first-person living history (M = 69.34, SD =10.03), and no living history (M = 66.84, SD = 12.24). The correlation between engagement and familiarity was .20 (p < .01). Within-group correlations were .17 (p <. 01), .12 (p = .04), and .28 (p < .01), in the relevance, dissonance, and control question types, respectively.

The group means suggest that both the living-history interpretation type and question type factors served to elevate visitor engagement in the sample data. For the question type variable, the means of both the relevance question condition (M=70.20) and the dissonance question condition (M=71.93) were higher than the customary question condition (M=67.79).

Four items were used as a manipulation check to measure guide behavior. These were taken from each participant at the conclusion of each tour. The means were consistently high, ranging from 8.02 (SD = 1.47) to 8.67 (SD = .62) on a 9-point scale. These results suggest a high degree of consistency in the delivery of the tours and a high level of commitment toward the interpretation.

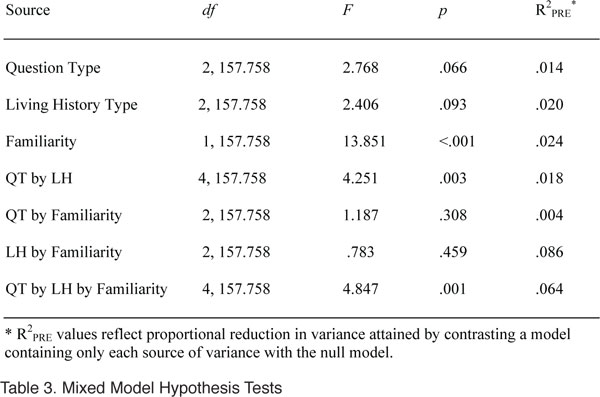

Hypothesis Tests

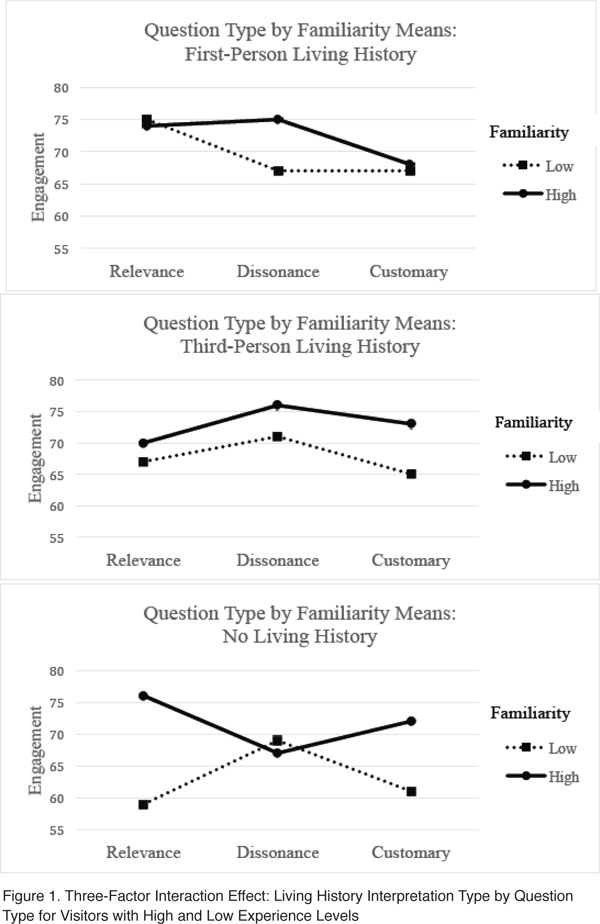

Results of the mixed model analysis are presented in Table 3. A significant three-factor interaction was found F(4, 157.76) = 4.85, p = .001. Two plots were constructed to facilitate interpretation of that interaction (Figure 1). Although the familiarity variable was treated as a continuous covariate in calculation of the F ratios, that variable was dichotomized to facilitate plotting and interpretation of the significant interaction. Thus, Figure 1 includes separate plots for visitors scoring below the median familiarity score (visitors with low familiarity) and visitors scoring above the median familiarity score (visitors with high familiarity).

Low-familiarity participants.

The plot of means of visitors with low familiarity (Figure 1) shows highest engagement scores for visitors who experienced third-person living history following both dissonance and relevance questions. Low-familiarity visitors in the no living history condition reported high levels of engagement only when dissonance questions were posed. When relevance or customary questions were posed to low-familiarity visitors in the no living history condition, engagement levels were lowest among all treatment combinations. Question type did not seem to differentially affect engagement of low-familiarity visitors who experienced first-person living history. For that group, all scores were clustered near the middle of the distribution, at 67.10 (the grand mean is 69.10).

High-familiarity participants.

The pattern of means for visitors with high levels of familiarity is quite different. When no living history is used with high-familiarity visitors, dissonance questions seem to decrease engagement. In the presence of both first-person and third-person living history, however, dissonance questions seem to evoke high levels of engagement. The opposite pattern appears to exist for relevance questions. When guests with high levels of familiarity are exposed to no living history, relevance questions evoke engagement. Engagement declines when relevance questions are used along with first-person living history, and relevance questions produce low engagement when used with high-familiarity visitors in third-person living history. Customary questions seem to evoke greater engagement in the no living history condition and the third-person living history condition. A decline in engagement is evident when customary questions are used with first-person living history.

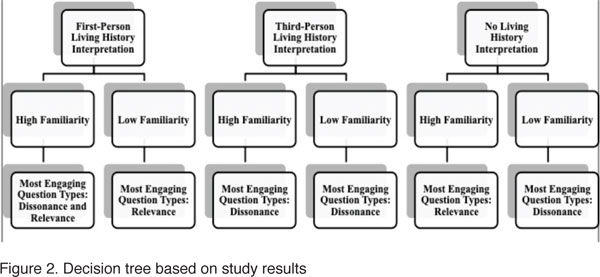

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of living-history interpretation type (i.e., first-person, third-person, none), question type (i.e., relevant, dissonant, customary), and familiarity on visitor engagement during a walking tour at a heritage site. Question type interacted with both interpretation type and level of familiarity. Visitors with low familiarity were most engaged when relevance or dissonance questions were asked during third-person living-history interpretation. In contrast, high-familiarity visitors reported highest levels of engagement in the following treatment conditions: No living-history interpretation with relevance questions, first-person living-history interpretation and both relevance and dissonance questions, and third-person living-history interpretation and dissonance questions. A decision tree based on the interaction effect is presented in Figure 2. This heuristic model suggests interpretation strategies that might be appropriate given visitors of high and low of familiarity. It is important to note, however, that this table is based on a single study at a unique heritage site. The recommendations should be regarded as preliminary and tenuous.

This three-factor interaction is consistent with Field and Wagar’s (1976) argument that visitors are diverse and an assortment of approaches to engagement will be required. It is also consistent with the long-practiced technique of attempting to know one’s audience before programming begins. Should the pattern of results shown in this study be verified with further research, it suggests best practices for enhancing interpretation programs. For example, if at Old Deseret Village, an interpreter knew that a participant, well-versed in Latter-Day Saint history wanted a guided tour, he or she might pull out all of the stops and give a first-person tour with a balance of dissonance and relevance questions to create high levels of engagement. However, if the interpreter, expert in the character to be portrayed, was unavailable, a third-person tour with only dissonance questions may also yield similarly high levels of engagement. Conversely, if the tour group was composed of visitors interested in, but uninformed of, Latter-Day Saint history, then a third-person tour with a balance of dissonance and relevance questions might be most engaging. Perhaps offering visitors with lower levels of knowledge too many engaging activities creates information overload and thus lower levels of engagement.

Results confirm what many interpreters have long known, namely, heritage tour interpretation and effective question asking may increase visitor engagement. This is salient because visitor engagement is a key element of quality interpretive experiences (Moscardo, 1999). The increased levels of attention, active participation, satisfaction, learning, and enthusiasm (Deci & Ryan, 2002; Reeve, 2012) as a result of increased engagement may allow for a richer and more meaningful interpretation experience. Consequently, a richer interpretation experience facilitates deeper pondering, reflection, and mindfulness (Ballantyne, Packer, & Falk, 2011; Moscardo, 2014; Walker & Moscardo, 2014) leading to changes in perception, behavior, attitude, and learning.

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations may have influenced the interpretation and generalization of results to other populations. These limitations include sample size, sampling techniques, and the ceiling effect described in the previous section. The study was limited to adults age 18 or older and was not designed to afford inferences about experiences of younger children. Although first-person living history did not produce engagement scores that were significantly different from third-person living history in the adult sample, a much different result might occur in a study of experiences of children and youth. Tilden (1977) emphasized the interpretation for children must be fundamentally different, and such successful experience offerings seem to focus on first-person living history for children and third-person for adults.

Finally, it is also notable that a single interpreter executed this experiment. The important question of engagement variability across different interpreters has not been addressed. Tilden (1977) emphasized that interpretation is a skill that may be learned, and interpreters with different levels of skill may produce very different levels of guest engagement. Variation in engagement as a function of differences in sites and contexts (e.g., museums, zoos, battlefields, rendezvous) sites has not been studied. Additionally, accumulation of effects from prior interpretive acts is indeed a threat to internal validity. We might argue, though, that conducting the field experiment using the organic procedures followed day-to-day at the heritage site would tend to build external validity.

Further research might be directed toward three areas. First, results of this study need to be replicated. This might be accomplished by using different interpreters, settings, and topics. Second, research might address the question of how tour type and question type are related to Tilden’s (1977) revelation and relate principles. The interaction effects with levels of familiarity suggest that much needs to be learned about how to more effectively connect to visitors of heritage tourism sites. Lastly, interpretation research may benefit from employing measures and examining propositions from the theory of structured experiences (Ellis et al., 2017).

References

Ablett, P. G., & Dyer, P. K. (2009). Heritage and hermeneutics: Towards a broader interpretation of interpretation. Current Issues in Tourism, 12(3), 209–233.

Ackerman, D. (2011). Deep play. Vintage.

Alexander, C.N., Langer, G.J., Newman, R.I., Chandler, H.M., & Davies, J.L. (1989). Transcendental meditation, mindfulness, and longevity: An experimental study with the elderly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 950–964.

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J. and Falk, J. ( 2011), Visitors’ learning for environmental sustainability: testing short- and long-term impacts of wildlife tourism experiences using structural equation modeling, Tourism Management, Vol. 32 No. 6, pp. 1243–1252 .

Beck, L., & Cable, T. (1998). Interpretation for the 21st century: Fifteen guiding principles for interpreting nature and culture. Champaign, IL: Sagamore.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology, 84(4), 822.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological inquiry, 18(4), 211–237.

Bruin, E. I., Meppelink, R., & Bögels, S. M. (2015). Mindfulness in higher education.

Csikzentmihalyi, M. (1992), “The flow experience and its significance for human psychology”, in Csikzentmihalyi, M. and Csikzentmihalyi, I.S. (Eds), Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 15–35.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002) ed. Handbook of self determination research. Rochester, NY: The University of Rochester Press.

Dewey, R. L. (1986). Porter Rockwell: A biography. Wantagh, NY: Paramount Books.

Dunn, T. L., & Risko, E. F. (2016). Understanding the cognitive miser: Cue utilization in effort avoidance.

Duvall, J. (2013). Using engagement-based strategies to alter perceptions of the walking environment. Environment and Behavior, 45(3), 303–322.

Ellis, G. D., Freeman, P. A., Jamal, T., & Jiang, J. (2017). A theory of structured experience. Annals of Leisure Research, 1–22.

Ellis, M. J. (1973). Why people play. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Field, D. R. & Wagar, J. A. (1976). People and Interpretation. In G. W. Sharp (ed). Interpreting the environment. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Frauman, E. (1999). The influence of Mindfulness of Information services and sustainable management practices at coastal South Carolina State Parks. Doctoral Dissertation, Clemson University. (UMI No. 9929721)

Frauman, E. (2010). Incorporating the concept of mindfulness in informal outdoor education settings. The Journal of Experiential Education, 33(3), 225–238

Fredricks, J. A., Bohnert, A. M., & Burdette, K. (2014). Moving beyond attendance: Lessons learned from assessing engagement in afterschool contexts. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2014(144), 45–58.

Ham, S. (1992). Environmental interpretation: A practical guide for people with big ideas and small budgets. Golden, CO: North America Press.

Hollister, O. J. (1886). Life of Schuyler Colfax. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Hunt, S. J. (2004). Acting the part: ‘living history’ as a serious pursuit. Leisure Studies, Vol. 23, No.4, 387–403, 2004.

Jones, G.R. & George, J.M. (2006). Contemporary management. (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Kang, M., & Gretzel, U. (2012). Perceptions of museum podcast tours: Effects of consumer innovativeness, internet familiarity and podcasting affinity on performance expectancies. Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 155–163.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. CUP Archive.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of environmental psychology, 15(3), 169–182.

Kaplan, S., & Kaplan, R. (1978). Humanscape. Landscape Journal.

Kaplan, S., & Talbot, J. F. (1983). Psychological benefits of a wilderness experience. Behavior and the natural environment, 6, 163–203.

Kim, J. H. (2016). Understanding narrative inquiry: The crafting and analysis of stories as research. Sage publications.

King, A., (2002). Guiding knowledge construction in the classroom: Effects of teaching children how to question and how to explain. American Educational Research Journal, 31(2), 338–368.

Lacanienta, A., Ellis, G., Taggart, A., Wilder, J., & Carroll, M. (2018). Does theming camp experiences lead to greater quality, satisfaction, and promotion? Journal of Youth Development, 13(1–2), 216–239.

Langer, E. J. (1993). A mindful education. Educational Psychologist, 28(1), 43–50.

Langer, E. (2000). The construct of mindfulness. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 1–9.

Langer, E. J. (2009). Counterclockwise: Mindful health and the power of possibility. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Langer, E. J. (2014). Mindfulness. Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Langer, E. J., & Moldoveanu, M. (2000). The construct of mindfulness. Journal of social issues, 56(1), 1–9.

Langer, E., Hatem, M., Joss, J., & Howell, M. (1989). Conditional teaching and mindful learning: The role of uncertainty in education. Creativity Research Journal, 2, 139–150.

Leff, H., Gordon, L., & Ferguson, J. (1974). Cognitive set and environmental awareness. Environment and Behavior 6, 395–447.

Luzader, J., & Spellman, J. (1996). “Living history: Hobby or profession?” Proceedings of the 1996 National Interpreters Workshop: 241–243.

Maslow, A. H. (1962). Lessons from the peak-experiences. Journal of humanistic psychology, 2(1), 9–18.

Maxwell, S. E., & Delaney, H. D. (2004). Designing experiments and analyzing data: A model comparison perspective (Vol. 1). Psychology Press.

Moscardo, G. (1996). “Mindful visitors heritage and tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 376–397.

Moscardo, G. (1999). Making visitors mindful: Principles for creating sustainable visitor experiences through effective communication. Champaign, IL: Sagamore.

Moscardo, G. (2001). Cultural and heritage tourism: The great debates. In B. Faulkner, G. Moscardo, & E. Laws (Eds.), Tourism in the 21st century (pp. 3–17). New York: Continuum.

Moscardo, G. (2009). Understanding tourist experience through mindfulness theory. In M. Kozak & A. Decrop (Eds.), Handbook of tourist behavior (pp. 99–115). New York, NY: Routledge.

Moscardo, G. (2014). Interpretation and tourism: holy grail or emperor’s robes? International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(4), 462–476.

Moscardo, G. (2017). Exploring mindfulness and stories in tourist experiences. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11(2).

Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (2011). The experience economy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (Vol. 1). Sage.

Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). Springer US.

Reeve, J. (2014). Understanding motivation and emotion. John Wiley & Sons.

Ritchhart, R., & Perkins, D. (2000). Life in the mindful classroom: Nurturing the disposition of mindfulness. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1) 27–47.

Sutcliffe, K., & Kim, S. (2014). Understanding children’s engagement with interpretation at a cultural heritage museum. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 9(4), 332–348.

Tilden, F. (1977). Interpreting our heritage. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

Walker, K., & Moscardo, G. (2014). Encouraging sustainability beyond the tourist experience: ecotourism, interpretation and values. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(8), 1175–1196.

West, B. T., Welch, K. B., & Galecki, A. T. (2007). Linear mixed model. Chapman Hall/CRC.