Contested Terrain

Attitudes of Lakota People Towards Interpretation at Wind Cave National Park

Dr. Dave Smaldone

Associate Professor

Recreation, Parks, & Tourism Program

Division of Forestry & Natural Resources

PO Box 6125

West Virginia University

Morgantown, WV 26506-6125

David.Smaldone@mail.wvu.edu

304-293-7404

Adam Rossi, M.S.

Highland School

arossi@highlandschool.org

Abstract

Wind Cave National Park (NP) in South Dakota has a long and complex history with local indigenous peoples, including the Lakotas. Wind Cave is the location of the Lakotas’ traditional origin story, and is now protected by a park representing a federal government that many indigenous peoples view negatively. The purpose of this exploratory study was to understand the attitudes of Lakotas toward Wind Cave NP and the interpretive stories it shares with visitors. Seventeen in-person interviews were conducted with Lakota people to understand their thoughts and feelings. Content analysis was used to uncover positive and negative themes about the park and various forms of interpretation. Findings indicate that park interpretation should include more Native perspectives, and recommendations are noted. The park should attempt to work more closely with Lakota and other local tribes, and can follow the examples of other National Park Service sites to accomplish these changes.

Keywords

native peoples, national parks, attitudes, interpretation, qualitative

Introduction

Wind Cave National Park in the Black Hills of South Dakota has a long and complex history concerning local indigenous peoples, including the Lakotas (Albers, 2003; Morrison, 2014; Reinhardt, 2015). Wind Cave is the location of the Lakotas’ traditional origin story, and is now protected by a park representing a federal government many indigenous peoples view negatively (King, 2007; LaVelle, 2001; Wooster, 1992). The Lakotas have long maintained that the Black Hills were illegally seized by the government in 1877, a claim that was upheld by the United States Court of Claims in 1979. The Lakotas were awarded $106 million at the time but declined to accept the money (this trust is now worth over $1 billion), insisting that it was not the money they wanted, but the land itself (Wooster, 1992). Efforts in the mid-1980s to return the park land to the Lakotas failed in the US legislative process (Wooster, 1992). Besides being significant to Lakota and other indigenous cultures, Wind Cave is the sixth-longest cave in the world and is often identified as one of the most complex cave systems (Spence, 2011). It was set aside as a national park in 1903, the first such designation to protect a cave.

Despite the tumultuous history, no study has attempted to characterize the attitudes of local indigenous people towards the park, nor its interpretation of Native peoples. Therefore the purpose of this exploratory study was to understand the attitudes of Lakotas toward Wind Cave NP and the interpretive stories it shares with visitors. The three research questions explored were:

- What are the attitudes of Lakota people towards Wind Cave National Park?

- What are the attitudes of Lakota people toward the National Park Service’s interpretation of Wind Cave?

- Do attitudes of Lakota people differ depending on their age (Anthony, 2007)?

Methods

Seventeen semi-structured in-person interviews using an interview guide (Allendorf, 1999; Turner III, 2010) were conducted in the summer of 2016 with Lakota tribal members at their homes to better understand their thoughts and feelings about the park and its interpretation. Once new information and themes stopped emerging from the interviews (i.e., data saturation occurred), data collection ended (Marshall, 1996). Criterion (age and gender) and snowball sampling techniques were used to identify the interviewees (Browne, 2005; Palinkas et al., 2015). To initiate the snowball sampling, the first contact was a tribal member (female, under 44 years of age) known by the researcher. She was asked for the names of five to 10 tribal members who could potentially be interviewed. Each person was contacted by phone and asked for permission to be interviewed. After interviewing those who agreed to be interviewed, each was then asked for the names of other people who could potentially be interviewed, and the sample continued to “snowball” in this manner. Respondents were grouped into two age groups during analysis, 18–44 years of age (younger) and 45+ (older). Respondents were almost equally split between young (9)/old (8) and male/female. Most interviews (16 out of the 17) were audio recorded with permission of the interviewee, transcribed, and then content analyzed using DeDoose, a web-based qualitative data analysis and management software. Responses were coded using both a priori and emergent categories, and these categories were organized thematically (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Results

Lakota Attitudes Towards Wind Cave NP

As the results are presented, example quotes that are representative of that category are included. Overall, results indicated that most tribal members had mixed opinions about the park. Positive themes frequently noted about the park in general included:

- preservation of an important resource (10 interviewees, or 59%) (e.g., “They made it a national park so that it can never be destroyed. I feel like if it wasn’t, then people would be exploiting it somehow. And I don’t feel like that’s being done.” Interviewee #4);

- the natural beauty (6, or 35%) (e.g., “It’s not so man-made, which I like about it…and trying to preserve the beauty that is our Black Hills.” Interviewee #7);

- recent improvements in park interpretation (5, or 29%) (e.g., “I remember [the visitor center] looked very upgraded from the last time I was there.” Interviewee #10).

Negative themes frequently discussed about the park in general were:

- the “touristy” aspects of Wind Cave (9, or 53%) (e.g., I kind of have mixed feelings about the intrusion of sacred places by mobs and mobs of people just to see it, you know, as spelunkers. It’s more of a commercial thing.” Interviewee #6);

- lack of Lakota perspectives in park interpretation (8, or 47%) (e.g., “I was looking around there, and I…made remarks about…hey, this is Native American, and there’s nothing that exists in there pertaining to Native Americans.” Interviewee #14);

- fees for cave tours (5, or 29%) (e.g., “I remember saying, ‘Why should I have to pay?’ You know, to go to something that has cultural, spiritual, and historical significance? Why did I have to pay to go back to my home?” Interviewee #6); and

- feelings of violation remaining due to their poor treatment in the Fort Laramie Treaty (4, or 24%) (e.g., “The entire [National Park System] needs to be made aware of the fact that number one, as to native cultures, to indigenous cultures, they are intruders. They are guests. And to remember that you’re not welcome guests to begin with.” Interviewee #17).

Eight tribal members (47%) made comments that suggested they were unfamiliar with park policies (e.g., some were unaware tribal members can go on cave tours for free). Sixteen interviewees (94%) made suggestions for park improvements, most frequently:

- Emphasize importance of cave to Lakotas to all visitors (“The Emergence Story is just as important [as] any [other] story that they’re telling. So it’s not something that should be glossed over; it’s not a footnote.” Interviewee #11)

- Hire Lakota staff members (“I know [a friend] was telling me that they’re trying to get more local people, more Lakota people to work there [Wind Cave], so I think if they keep trying to do that it would be good….” Interviewee #2)

- Include a broader Lakota people’s perspective (“I think that they mainly have just Oglala right now. And they always say ‘the Lakota people,’ but there are seven bands. We’re all different. I think it’s just important to not make it about the Oglalas just ‘cause we’re closest.” Interviewee #4)

Lakota Attitudes Towards Interpretation at Wind Cave NP

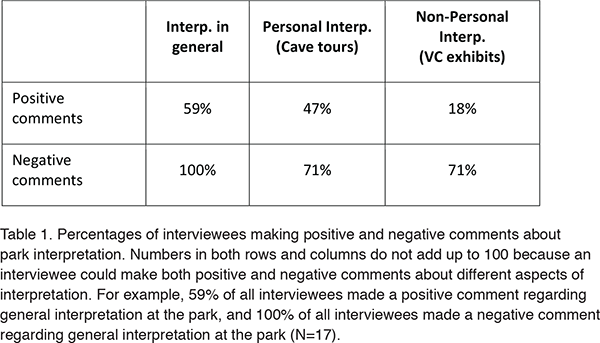

Positive and negative comments related to interpretation in general, as well as both personal interpretation (cave tours specifically), and non-personal interpretation (the visitor center exhibits specifically) are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 59% (10 interviewees) made positive comments about park interpretation, most frequently about including Lakota perspectives and sharing scientific information. All interviewees made negative comments about interpretation, and the most frequent negative comment noted the lack of Lakota perspectives present in the existing interpretation.

As seen in Table 1, a similar percentage (71%) of respondents made negative comments about both cave tours and the exhibits, but a much smaller percentage (18%) made positive comments about the exhibits compared to 47% who had positive comments about cave tours. The most commonly reported (29%) positive thematic category about cave tours was appreciation for the inclusion of Lakota perspectives on cave tours, as interviewee #7 noted: “…I really liked the tour that the ranger gave us. …from what I’ve heard, she told the [Emergence] Story very accurately, and she gave a lot of information.” Interestingly, the most commonly reported negative thematic category about cave tours was that the tours did not adequately emphasize or respect the Lakotas’ viewpoints of Wind Cave (9 people, or 53%). As interviewee #11 stated, “If anything was mentioned about the Lakota people, it was mentioned in passing. Entirely. And that’s actually still a problem that exists.”

Few interviewees (3, or 18%) expressed positive thoughts or feelings towards the visitor center exhibits at the park, and all of those comments related to the improvements being planned for the exhibits. Twelve interviewees (71%) made negative comments about the exhibits, most frequently (10 interviewees, or 59%) that Lakotas’ viewpoints are not adequately represented in the exhibits. As one interviewee (#11) noted, “You know, it’s very dismissive, it’s very insulting. The time periods that are addressed with regard to Native Americans are past tense. I mean, we don’t exist anymore.” Two other common negative comments were that information contained in the exhibits was inaccurate, and the neglect of Lakotas perspectives was purposeful on the part of the park (both noted by three interviewees each, or 18%).

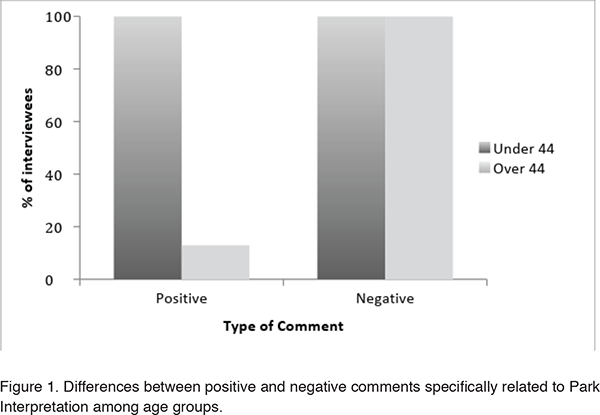

Difference in Attitudes Between Age Groups

The majority of interviewees, both younger and older, made both positive and negative comments about the park in general, with younger Lakotas tending to make more positive and less negative comments than older Lakotas. However, clear age differences emerged specifically related to Park interpretation. All younger Lakotas (9 out of 9) made positive comments, but only 13% of older Lakotas (1 out of 8) made positive comments (Figure 1). Finally, all interviewees, regardless of age, made negative comments about park interpretation.

Additional differences among older and younger Lakotas were noted related to the types of comments. For example, 56% of the younger group made comments about improvements at the park, but only 13% of the older group made such comments. Similarly, 44% of younger Lakotas stated that the park was willing to make positive changes, but none of the older Lakotas made such comments. One hundred percent of younger Lakotas suggested that the park should better emphasize the Emergence Story and Lakota perspectives, while only 63% (5 out of 8) of older Lakotas made similar suggestions.

Discussion & Management Implications: Respect & Encourage Tribal Voices

Results reveal most of the Lakotas interviewed think the park needs to better communicate the cultural significance of the cave and encourage visitors to be more respectful. Many interviewees felt Lakota “neglect” is a problem—the Lakota perspective(s) are missing in most of the interpretation at the park. Interestingly, results also found that many Lakotas lacked awareness regarding the policies the park has in place that pertain to Lakotas. For example, some interviewees complained of having to pay a fee to go on a cave tour, even though the park offers free cave tours to any enrolled member of 21 federally recognized tribes. Results indicate the park should continue to actively try to build stronger relationships with local tribes (Albers 2003; Tuxill et al., 2009), and the tribes themselves may also want to reach out to the park. Similar issues related to Native Peoples exist at Devils Tower, Apostle Islands, and Mount Rainier for example, so NPS sites (and other federal agencies) should continue to work together to develop and implement best practices regarding tribal collaborations (Keller & Turek, 1998; Parks Canada, 2016; Tuxill et al., 2009; Whisnant et al., 2011).

The main difference between younger and older Lakotas was that the younger generation were more likely to say something positive about the interpretation, but almost none of older generation interviewees did so. As the park works more with Lakotas, it is recommended they specifically reach out to older generations as they seem to be less positive towards the park, especially in regards to their views on current park interpretation.

Based on the interviewees’ suggestions, the following things are specifically recommended to improve the relationships with Native Peoples at Wind Cave NP, as well as to improve the interpretation related to Lakotas. Some of these recommendations came directly from interviewees, others are based on best practices to collaborate with Native peoples:

- Invite more collaborative opportunities; encourage hiring of more indigenous staff members; and invite tribes to showcase perspectives regularly (Ostler, 2011).

- Require Tribal perspectives to be shared on all cave tours, which are easier to “update” than visitor center exhibits.

- Develop more non-personal interpretive opportunities (i.e., site bulletins) with Tribal consultation and collaboration.

- As the older and more expensive exhibits are replaced, NPS planners should work collaboratively with tribal members to incorporate more diverse Lakota perspectives.

- Encourage NPS staff to integrate more Lakota stories and perspectives into non-cave programs, to demonstrate that the cave is not the only important resource to indigenous people.

Acknowledgments

This research came to fruition only with the help of many people who were generous with their time, talents, and thoughts. First and foremost, many thanks are extended to the 17 Tribal members who agreed to share their thoughts and feelings that made this study possible. Thanks also to the staff at Wind Cave National Park for their openness and help throughout this study, particularly to Tom Farrell, the Chief of Interpretation. A special thanks is also extended to Sina Bear Eagle, who provided the inspiration for this study and whose help along the way was indispensable.

References Cited

Albers, P. C. (2003). The home of the bison: An ethnographic and ethnohistorical study of traditional cultural affiliations to Wind Cave National Park. Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota.

Allendorf, T. D. (1999). Local residents’ perceptions of protected areas in Nepal: Beyond conflicts and economics (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN.

Anthony, B. (2007). The dual nature of parks: attitudes of neighbouring communities towards Kruger National Park, South Africa. Environmental Conservation, 34(3), 236–245.

Beltrán, J. (Ed.) (2000). Indigenous and traditional peoples and protected areas: Principles, guidelines and case studies. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/WWF International.

Browne, K. (2005). Snowball sampling: using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 47–60.

Dustin, D. L., Schneider, I. E., McAvoy, L. H., & Frakt, A. N. (2002). Cross-cultural claims on Devils Tower National Monument: A case study. Leisure Sciences, 24(1), 79–88.

Federal Preservation Institute. (n.d.). Consultation with Native Americans: A historic preservation responsibility. Retrieved from http://www.achp.gov/docs/nafolder.pdf.

Fernández-Baca, J. C., & Martin, A. S. (2007). Indigenous peoples and protected areas management innovations in conservation series, parks in peril program. Arlington, VA: The Nature Conservancy.

Hsieh, H. F. & Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Keller, R. H. & Turek, M. F. (1998). American Indians & National Parks. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

King, M. A. (2007). Co-management or contracting?: Agreements between Native American tribes and the U.S. National Park Service pursuant to the 1994 Tribal Self-Governance Act. Harvard Environmental Law Review, 31, 475–530.

LaVelle, J. P. (2001). Rescuing Paha Sapa: Achieving environmental justice by restoring the great grasslands and returning the sacred Black Hills to the Great Sioux Nation. Great Plains Natural Resources Journal, 5, 40.

Mahoney, M. (2011). This land is your land, this land is my land: An historical narrative of an intergenerational controversy over public use management of the San Francisco Peaks (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from https://repository.asu.edu/attachments/56997/content/Mahoney_asu_0010N_10960.pdf.

Marshall, M. N. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 13(6), 522–525.

McAvoy, L., McDonald, D., & Carlson, M. (2003). American Indian/First Nation place attachment to park lands: The case of the Nuu-chah-nulth of British Columbia. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 21(2), 84–104.

Morrison, S. (2014). In kind or monetary restitution: Historic wrongs and indigenous land claims. Journal of Politics and Law, 7(2), 50–62.

Ostler, J. (2010). The Lakotas and the Black Hills. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544.

Parks Canada. (2016). Best practices and lessons learned in indigenous engagement. Retrieved from: http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/agen/aa/te-wt/introduction.aspx.

Reinhardt, A. D. (2015). Welcome to the Oglala Nation: a documentary reader in Oglala Lakota political history. Retrieved from: site.ebrary.com.www.libproxy.wvu.edu/liblnwvu/detail.action?docID=11081698.

Rights and Resources Initiative. (2015). Protected areas and the land rights of indigenous peoples and local communities: current issues and future agenda. Washington, D.C.: Rights and Resources Initiative.

Spence, M. D. (2011). Passages through many worlds: historic resource study of Wind Cave National Park. Retrieved from: www.nps.gov/wica/learn/historyculture/upload/WICA_HRS-2.pdf

Steelman, T. A. (2001). Elite and participatory policymaking: Finding balance in a case of national forest planning. Policy Studies Journal, 29(1), 71–89.

Stevens, S. (Ed.). (1997). Conservation through cultural survival: Indigenous peoples and protected areas. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Turner III, D. W. (2010). Qualitative interview design: A practical guide for novice investigators. The Qualitative Report, 15(3), 754–760.

Tuxill, J. L., Mitchell, N. J., & Clark, D. (2009). Stronger together: A manual on the principles and practices of civic engagement. Woodstock, VT: Conservation Study Institute.

Whisnant, A. M., Miller, M. R., Nash, G. B., & Thelen, D. (2011). Imperiled promise: The state of history in the National Park Service. Bloomington, IN: Organization of American Historians.

Worster, D. (1992). Under western skies: Nature and history in the American West. Oxford, England, U. K.: Oxford University Press.