The Place of Inspiration in Heritage Interpretation

A Conceptual Analysis

Dr. Jacquline Gilson

Parks Canada and InterpActive Planning

C/o 11 Grotto Close

Canmore, AB, Canada, T1W 1K4

Jacquie@interpactiveplanning.ca

403 609 8594 Cell

Dr. Richard Kool

School of Environment and Sustainability, Royal Roads University

Victoria BC Canada V9B 5Y2

Rick.Kool@RoyalRoads.ca

250 391 2523 Phone

Abstract

Inspiration has been an under-studied phenomenon in the interpretation field. This paper presents the results of a systematic literature review of psychological literature related to inspiration, revealing nine characteristics of inspiration. Of particular interest was the contrasting meanings of inspiration as inspired by and inspired to, and that inspiration is transmissible, positive, individual, transcendent, unexpected, and holistic, and requires receptivity, which may be cultivated. Each characteristic was related to the field of interpretation in practice. After this review of the literature, we propose that giving consideration to inspiration-based interpretation may provide useful insights for practice as a constructivist approach to interpretation. Further exploration into the topic is warranted.

Keywords

inspiration, provocation, inspiration-based interpretation, qualitative research, literature review, constructivist

Introduction

The concept of inspiration has not been the focus of any inquiry within heritage interpretation, although the term is used regularly within the field. The word inspiration is also used in everyday contexts and is increasingly being investigated within the field of positive psychology, resulting in a growing body of literature (Gotz, 1998; Hart, 1993, 1998; Kwall, 2006; Montuori, 2011; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Simopoulos, 1948; Thrash & Elliot, 2003, 2004). Research into the synergies between the concept of inspiration as identified in the psychological literature, and the field of interpretation, could provide useful insights for interpretation in practice and the purpose of this paper is to explore these potential synergies.

Over the past decades, interpretation has been slowly moving from having an education- and knowledge-based epistemological foundation to a more constructivist and visitor-oriented foundation. As the instrumental knowledge-based view of interpretation is being questioned, there is an abundance of literature encouraging more holistic interpretation, i.e., reaching out to visitors through the affective and connative domains, in addition to the cognitive domain (Ballantyne, Packer, & Falk, 2011; Ballantyne, Packer, Hughes, & Dierking, 2007; Beck & Cable, 2011; Davidson & Black, 2007; Hughes, 2012; Hunter, 2012b; Ingham, 2000; Knapp & Forist, 2014; Martin, 2011; Mitchell, 2005; Wijeratne, Van Dijk, Kirk-Brown, & Frost, 2014). Advocates for constructivist-based interpretation encourage visitors to actively make meaning based on their previous knowledge and experiences, rather than passively receiving information (Shalaginova, 2012). For example, Staiff wrote that interpretation, “rather than being a matter of communicating something to a (passive and temporary) visitor … is the production of meaning by the visitor in their interaction with the place” (2014, p. 24). In this constructivist context, we can understand interpretation as a process of assisting desired meaning-making through the provision of a range of experiences, all of which may lead to greater and deeper understandings on the part of the participant.

Concepts from the psychology literature on inspiration have provided us with useful insights for constructivist-based interpretation. Inspiration is defined as a “breathing in or infusion of some idea, purpose, etc., into the mind; the suggestion, awakening, or creation of some feeling or impulse, especially of an exalted kind” (Oxford University Press, 2000, p. Section II 3b). Attempting to operationalize this rather general definition, inspiration researchers Thrash and Elliot (2003) identified a number of important attributes of inspiration, “Inspiration implies motivation…; inspiration is evoked rather than initiated directly through an act of will…; and inspiration involves transcendence of the ordinary preoccupations or limitations of human agency…” (p. 871, emphasis added). More recently, reflecting an effort to try and provide a synthesis of the concept, Chadborn and Reysen (2016) asserted that, “inspiration acts as a motivational concept, in which inspiration is evoked (generated) from a source and a person then finds some means to transmit an idea and is driven to produce some creative outcome as a result” (p. 1). The benefits of inspiration include well-being (Hart, 1993; Thrash, Elliot, Maruskin, & Cassidy, 2010; Thrash, Maruskin, Cassidy, Fryer, & Ryan, 2010), creating tangible objects such as art (Engen, 2005; Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010; Thrash, Moldovan, Oleynick, & Markusin, 2014), making life worth living (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), helping people flourish (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997), and meeting people’s need for seeking higher ideals upon which cultures are based, such as creativity, meaning, and spiritual truth (Thrash & Elliot, 2004). Simopoulos (1948, p. 35) described inspiration as “the answer to a deep human need” and Hart (1993) explained it as a subtle and ephemeral event. While Thrash and Elliot (2003) have developed and validated an Inspiration Scale that assesses inspiration frequency and intensity, this scale has not yet been applied to the interpretation setting. The benefits of inspiration are widely acknowledged and its general qualities seem, to us, an ideal fit with the interpretation field.

The topic of inspiration is a natural fit for interpretation and the idea of inspiration is not a new one for the field of heritage interpretation. Enos Mills used the term inspirational to refer to interpretation in 1920, pointing out, “nature guiding, as we see it, is more inspirational than informational” (2001, p. 142). Freeman Tilden (1977) suggested that the interpreter’s passion can act as a model to inspire visitors. Canadian R. Yorke Edwards stated “interpretation’s aim is inspiration and revelation, leaving people’s lives never quite the same again because of new interest and understanding” (1979, p. 23), and noted, “I am a firm believer in the value of interpretation not so much because I have seen its inspiration in others, but because I have received its inspiration myself. And I thoroughly enjoy being inspired” (p. 15). Beck and Cable (2011) described the purpose of the interpretive story as to inspire and provoke the audience, and their last three “gifts” of beauty, joy, and passion have similarities to inspiration. Widner-Ward and Wilkinson included a section on inspiration in their textbook, where they described the ultimate goal of interpretation as “to inspire others to want to explore further, to learn more on their own” (2006, p. 23). And in a dissertation focused on place and interpretation, one of the research participants exclaimed that inspiration is “an ultimate goal for interpretation” (Hunter, 2012a, p. 127).

The term inspiration is also used by a range of organizations offering interpretation, showing that the concept is considered important in the field of practice. For example, Parks Canada’s slogans are “Real. Inspiring” and “Inspiring Discovery” (Government of Canada, 2013), while the mission statement of the National Association for Interpretation in the United States is, “inspiring leadership and excellence to advance heritage interpretation as a profession” (National Association for Interpretation, 2014) and the U.S. National Park Service Education Plan for Denali National Park indicated that inspiration is a desired visitor outcome (US National Park Service, 2009).

While the term inspiration has been used for the last 100 years in interpretation, inspiration-focused research in the field is nonexistent to date in either Canada or the United States. A search on Interpretation Canada’s website for the word inspiration in the articles of the InterpScan journal revealed that the term was not used in any of the available titles between 2002 and 2017. A search of all current and archived issues of the Journal of Interpretation Research revealed that inspiration was not used in the title or abstract of any articles, and that the word showed up in the text of only eight articles from 2005 to 2012 and even then, not in an analytical context.

There are at least two references to concepts similar to inspiration within the interpretation literature. First, LaPage (2001) described “eureka moments,” noting that these moments 1) follow an orderly sequence of events, 2) that people need to be receptive to them, and 3) that we may never know the effects of them on people. These attributes are similar to those described in the inspiration literature.

Second, the term provocation has been used in interpretation for at least 50 years, with the terms provocation and inspiration seemingly used interchangeably. For example, Tilden’s principle four stated that “the chief aim of Interpretation is not instruction, but provocation” (1977, p. 32), Beck and Cable (2011) refer to provocation as their fourth principle, and in Sam Ham’s newest textbook (2013), the term provocation is referenced 119 times in the index, while the term inspiration is not used at all. While Ham does not define provocation in his text, he refers to provocation as one of the three possible endgames for interpretation, along with teaching and entertainment. Ham seems to use the term in the same manner as Tilden; both suggest that interpreters need to provoke visitors to think and make their own meanings. A search for the term provocation in peer-reviewed journals, including the interpretation field and beyond, indicated that the term has not been the focus of any recent research in any field, with the exception of the law profession. The Oxford Online dictionary defines provocation as “Action or speech that makes someone angry, especially deliberately,” although an older usage is that of posing a challenge, while in law, the term refers to action or speech likely to incite retaliation (Oxford University Press, 2019b). While provocation in current usage seems to be associated with deliberately provoking or making someone angry or at least presenting a challenge to a person, the term inspiration seems to be related to uplifting experiences, as shown in the review of the inspiration literature (see below). The role of the term provocation relative to the term inspiration was not a focus for this paper and is still waiting for a rigorous examination.

Methodology

The methodology for this paper consisted of an extensive systematic literature review focused on the topic of inspiration, involving both social science (psychology and heritage interpretation fields) and humanities (philosophy) literature, as this approach seemed well-suited to a conceptual analysis (Fink, 2010). We used existing studies and writings as our analytical data.

For Fink, “A literature review is a systematic, explicit, and reproducible design for identifying, evaluating, and interpreting the existing body of completed and recorded work produced by researchers, scholars, and practitioners” (2010, p. 3). Following her framework, we developed our research question, chose our sources and search terms, applied our search terms, evaluated the adequacy of each study’s coverage, completed the review, and compiled the results (Fink, 2010). It is from the synthesis of the results that we developed our conceptual analysis.

Conceptual analysis in this sense is the attempt to break down ideas into their constituent parts, and we have searched within the broad usage of the term inspiration within a wide range of literature, for those pieces that are both constituent of and related to our work in interpretation. This approach was also useful for identifying gaps in the current research and for formulating exploratory research questions for further investigation. An extended thematic analysis (Ryan & Bernard, 2003) was used to code the various definitions and meanings of the term inspiration from across the disciplines, and from the codes we generated the nine themes that are the primary focus of this project.

We made extensive use of the Royal Roads University Library’s (RRU) Discovery search engine, as well as Google Scholar to carry out this literature review. Terms utilized in our searches included inspiration and inspire, and these terms were placed against interpretation, heritage interpretation, participation, psychology, community, creativity, and spirituality, as in inspiration AND psychology. Each “hit” was examined by the senior author, who made an immediate decision as to the relevance of the source. We were not interested in non-academic and non-professional literature and focused our attention on the literature we felt would help us to elucidate the meaning of the focus term inspiration within the context of the heritage interpretation field. Given that inspiration-related searches resulted in tens of thousands of hits, we needed to ensure that we cut this huge number down by restricting our initial search to journal articles rather than books and removing references that seemed to be of lesser utility given our research interest (Fink, 2010).

The inspiration literature is dominated by a few scholars and their contributions weighed heavily in the analysis, which really was meant to provide means for us to investigate and then create a picture of how inspiration could fit into the interpretation field. The literature review was not intended to be broadly exhaustive as our purpose was really quite narrow, and once a particularly relevant reference was found, its citation list became a fruitful source for further investigation.

By the end of this literature review process, the senior author had accumulated over 130 papers relevant to the topic of inspiration and interpretation and these were reviewed and analyzed to create the framework reported here. Locke, Spirduso, and Silverman, in Hesse-Biber and Leavy (2011, p. 43) recommend thinking of the literature review as an “extended conversation”; with this notion in mind, we hope that this paper will be a conversation starter.

Results

Inspiration: An Introduction

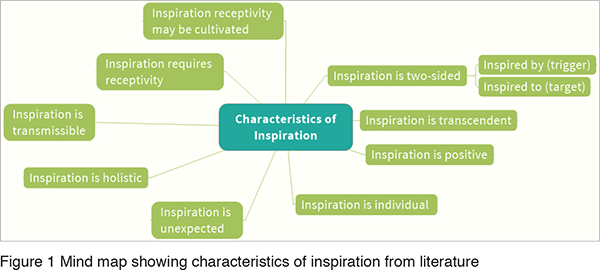

Inspiration seems to be a complex and mysterious concept; however, we have identified commonalities in the reviewed literature. We have deconstructed the concept into nine characteristics of inspiration as described in the following paragraphs and illustrated in Figure 1. This representation is a Mind Map, a tool defined as “a diagram in which information is represented visually, usually with a central idea placed in the middle and associated ideas arranged around it” (Oxford University Press, 2019a).

Inspiration is two-sided. The literature demonstrates that inspiration encompasses two key elements: the trigger, or what people are inspired by; and the target, or what they are inspired to do or be (Hart, 1993, 1998; Jennings, 2012; Thrash & Elliot, 2003, 2004; Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010; Thrash, Maruskin, et al., 2010; Thrash et al., 2014). Both manifestations of inspiration are necessary and linked (Gonzalez, Metzler, & Newton, 2011; Hart, 1993, 1998; Simopoulos, 1948; Thrash & Elliot, 2003, 2004; Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010), and Jennings (2012) pointed out that both sides of inspiration are required in order to differentiate it from emotions such as awe or wonder.

While the trigger, or what people are inspired by, varies from person to person, there are commonalities. Hart’s (1993) pioneering research with college students determined that typical triggers of inspiration were nature, love, suffering, courage, music, exercise, religion, beauty, and quality, with nature being the most commonly reported external source of inspiration. Thrash and colleagues continue to advance the study of inspiration and have reported that inspiration may come from within or without, and that people may be inspired by encounters with a person, object, act, or idea (Thrash & Elliot, 2003, 2004; Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010; Thrash et al., 2014). Other researchers have added to this list, noting that internal sources of inspiration may include supernatural sources such as a deity or spirit, or ideas such as truth, beauty, or goodness (Hart, 1993; Simopoulos, 1948; Thrash & Elliot, 2003). External sources of inspiration may include other people (i.e., mentors or high-achieving role models); objects in the environment such as nature, music, or literature; or undertaking an activity such as making a fire, enjoying a cup of tea, watching a motivational video, or taking part in a physical activity (Gonzalez et al., 2011; Hart, 1993; Kwall, 2006; Thrash & Elliot, 2003, 2004).

The target, or what people are inspired to, also shows both variation and similarities from person to person. Hart (1993) found that for college students, inspiration manifested in actions such as sharing the inspiration with others through talk, art, writing, photography, or efforts for self-improvement. Other researchers have added that inspiration may manifest in achieving success in sports or academics, improving the self, achieving a personal goal, solving a problem, creating something, being transformed, or supporting a cause (Gotz, 1998; Hart, 1993, 1998; Jackson, 2012; Kwall, 2006; Thrash & Elliot, 2003, 2004; Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010). Described as “approach motivation” inspiration, Thrash and colleagues (Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010; Thrash et al., 2014) explain that this side of inspiration involves energy and action (i.e., being intrinsically-motivated with no thought of reward). Hart (1993) noted that people must be both passive and active for inspiration to occur, i.e., passive and open to inspiration, then active after being inspired. Hart (1998) also pointed out that the target of inspiration may manifest in the form of action (i.e., doing something), or it may manifest in being (i.e., inspired to just be, in other words, a non action, such as self-reflection or a transformation of one’s being).

Inspiration is transcendent. Described by the 17th-century Welsh author Henry Vaughan as “bright shoots of everlastingness” (Simopoulos, 1948, p. 32), transcendence is one of inspiration’s core characteristics (Hart, 1998; Jennings, 2012; Thrash & Elliot, 2004; Thrash, Maruskin, et al., 2010; Thrash et al., 2014). Inspiration involves being in the moment, and at the same time losing that moment. When a person is inspired they are in a special zone—others have described similar constructs, such as “flow” by Csikszentmihalyi and colleagues (Abuhamdeh & Csikszentmihalyi, 2012; Csikszentmihalyi, 1997; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), “peak experience” by Maslow (1964, 1968), “mental stillness” by Hart (1993) and “a moment of extreme happiness; a feeling of lightness and freedom; a sense of harmony with the whole world; moments which are totally absorbing and which feel important: these phrases characterize transcendent experience” (Williams & Harvey, 2001, p. 249). Inspiration may also be associated with spiritual experiences; for example, during a wilderness trip, participants indicated that the setting and social interaction combined to produce spiritual inspiration (Fredrickson & Anderson, 1999). Williams and Harvey (2001) found, in their study of 131 individuals “who visit, work, or live in forests” (p. 251), many expressions of a profound sense of transcendence in forest settings, settings that evoke responses that would be quite familiar to many interpreters.

Inspiration is positive. Connected to this idea of transcendence, inspiration is seen as being mainly positive and joyful (Jennings, 2012), and although it may be brought on by a difficult experience, the inspiration itself is seen as uplifting, expansive and elevating (Hart, 1998; Thrash & Elliot, 2003; Thrash et al., 2014). Haidt (2000) describes inspiration as “a warm, uplifting feeling that people experience when they see unexpected acts of human goodness, kindness, and compassion” (pp. 1–2).

The consequences of inspiration were described in positive words by Hart’s research participants as being “energized, open, clear, loving, helping others, having meaning, creating, connected, confident, humbled, joyous, and alive” (1993, p. 162). Thrash and Elliot described the inspired state as being characterized by “feelings of connection, openness, clarity, and energy” (2003, p. 873) and Thrash and colleagues (2010) also noted that people usually feel the positive emotion of gratitude towards the source of their inspiration.

Inspiration is individual. Studies into inspiration as a psychological concept acknowledge that inspiration is open to all individuals. Research indicates an evolution in thinking from the term’s early use in religious contexts and its relationship to creative genius only, to its modern-day secular use; “rather than a rare event reserved for the gifted artist or great mystic, inspiration appears to be something that all of us experience and have some understanding of” (Hart, 1993, p. 159). However, what one person is inspired by and inspired to may be very different than what another person is inspired by and inspired to (Jennings, 2012). Inspiration is also individual in the sense that the inspiration may or may not be visible to the world (Hart, 1998; Thrash & Elliot, 2003); and there may be a lag between the two sides of inspiration, depending on each person’s response. For example, Hart (1993) noted that the recipient of inspiration was often compelled to communicate the idea while it was still fresh, i.e., to immediately validate the experience and capture the idea, with no time lag between the inspired by and inspired to phases. However, he also pointed out that the target of inspiration may come later, (e.g., at an unexpected time) and may not be visible (1998). Similarly, Thrash and Elliot (2004) noted that in some cases there may be no apparent outlet for the inspiration (e.g., a person may be inspired by the beauty of the Grand Canyon, but have no immediate outlet for that inspiration and therefore may not act on the inspiration right away), although it may manifest at a later time.

Inspiration is unexpected. Inspiration is accidental or unwilled, and it may come along in leaps and bounds or slowly (Hart, 1998; Jennings, 2012; Thrash & Elliot, 2004). This sense has also been described by Thrash and Elliot (2003) and Thrash, Moldovan, Oleynick, and Maruskin (2014), and according to Shiota, Thrash, Danvers, and Dombrowksi, “one does not feel directly responsible for becoming inspired, and ascribes responsibility for inspiration to something beyond one’s own will” (2017, p. 369). Inspiration may be out of a person’s control and may involve a flash, an aha moment, a breakthrough, something that is unexpected or, as described by Gotz, “the instant when things ‘click’ and fall neatly into place, or a new idea flashes in the dark” (1998, p. 510). This notion is similar to the previously described interpretive “eureka moments” (LaPage, 2002). Inspiration involves people giving up control and in describing the moment of inspiration, Thrash et al.’s research participants explained feeling that the situation was outside of their power and control and the authors noted that this seemed to be difficult for their participants to admit in our individualistic and strength-oriented society (Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010; Thrash, Maruskin, et al., 2010).

Inspiration is holistic. Inspiration has been described as bringing the rational and non-rational together (Gotz, 1998; Hart, 1998; Thrash & Elliot, 2003) and may be a good example of the growing understanding about the close links between cognition and emotion coming out of a range of fields (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007; Pessoa, 2008). Thrash and Elliot noticed that inspiration “engages the head as well as the heart” (2003, p. 878), Engen described inspiration as involving the whole person; “emotional, behavioral, intellectual, and sensory” (2005, p. 16), while Hart referred to inspiration as “full body knowledge” in which emotion and cognition are simultaneously experienced (1998, p. 19). Gotz described inspiration “as a madness, inspiration impels artists on, but only knowledge can guide their search. If inspiration is like the wind all vessels need for movement, knowledge is at the helm” (1998, p. 512). Some scholars have pointed out that for people to experience success based on inspiration, they will need the necessary knowledge and technical proficiency to be able to successfully act on the inspiration (Hart, 1993; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000; Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010). British novelist Anthony Burgess (1986) put this holistic concept together when he wrote, “Art begins with craft, and there is no art until craft has been mastered….” (section 7, p. 47).

Inspiration is transmissible. Different authors have pointed out that inspiration may be contagious and self-perpetuate (Brenneman, 2012; Hart, 1993, 1998). As an important contributor to well-being, inspiration may help people flourish and its ability to spread is usually welcome (Hart, 1993; Jennings, 2012). Thrash and colleagues (Thrash & Elliot, 2004; Thrash et al., 2014) note recipients of inspiration often have a need to share the inspiration with others; the inspiration is not the end experience but simply one link in a transmission in pursuit of higher goals. While social interactions as sources of inspiration have not been investigated to any great extent (e.g., Milyavskaya, Ianakieva, Foxen-Craft, Colantuoni, & Koestner, 2012), Hart (1993) noted that it would be instructive to study collective inspiration, i.e., how people may be inspired by others at a place or event. Indeed, Margaret Mead’s famous aphorism, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has” is really all about the transmission of inspiration from a small group to others.

Recent work has taken a social identity approach (Turner, 1975) focusing on the transmission of inspiration as influenced by the relationship between an individual’s self-concept and their sense of social identity. Social identity relates to how individuals “define themselves in terms of a shared group membership…” (Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., & Platow, 2011, p. xxii). Findings (Chadborn & Reysen, 2016), while preliminary, indicate research participants were more likely to be inspired by members of a group that they saw themselves as a member of (i.e., by members of their in-group):

Overall, the results provide strong support indicating not only a relationship between in-group identification and inspiration, but that when made salient, an individual’s in-group can act as a strong determinant for the frequency and intensity of inspiration gained when thinking about one’s group. (p. 6)

Inspiration requires receptivity. While inspiration is seen as being outside the control of a person, receptivity to inspiration is required (Hart, 1993, 1998, 2004; O’Grady & Richards, 2011; Thrash & Elliot, 2004; Thrash, Elliot, et al., 2010; Thrash, Maruskin, et al., 2010; Thrash et al., 2014). Receptivity may take the form of tolerance for ambiguity, divergent thinking, focus, trust, letting go, or listening (Hart, 1993, 1998). Thrash and Elliot (2003) discovered that positive affect and openness to experience were traits that were positively correlated with inspiration, and that inspiration also correlated positively with intrinsic motivation (i.e., doing things for their own value) but negatively with extrinsic motivation (i.e., doing things because you’ll get a reward), suggesting that certain personality traits may predispose a person to being more or less receptive to inspiration.

Some research has shown that inspiration is experienced to a greater degree the more the stimulus is in line with a person’s values, i.e., people are more receptive to being inspired by content that already fits with their existing beliefs. For example, in a dissertation that explored inspiration as a state, Jennings (2012) determined that “inspiration does not necessarily relate to general prosocial behavior; rather, it relates to specific content domains when those domains are aligned with one’s enduring interests and values” and inspiration is “experienced to a greater degree when the content of a particular stimulus is more congruent with one’s internalized values or interests” (pp. 73–74).

In summary, in order for inspiration to occur, whether through personal traits or aligned values, people must be open and receptive to it.

Inspiration receptivity may be cultivated. Inspiration may not be forced, but it may be wooed, as described by Hart; “although it does not seem possible to will inspiration into existence, it does seem likely that we can set up favorable conditions to woo or invite it” (1998, p. 26). The psychological literature contains many suggestions for wooing or cultivating receptivity to inspiration, including:

- being open and contemplative, seeking it, reading, meditating, dialoguing, focusing, trusting, letting go, listening, and understanding that inspiration exists (Hart, 1993, 1998, 2004; O’Grady & Richards, 2011);

- being exposed to high-achieving role models (Thrash & Elliot, 2003);

- collaboratively creating new futures (Montuori, 2011);

- receiving a pep talk or watching an inspirational video (Gonzalez et al., 2011);

- setting goals, particularly successful in people with high trait inspiration (Milyavskaya et al., 2012);

- being open to new ideas and motivationally responsive to those ideas (Thrash, Maruskin, et al., 2010); and

- having high attentional involvement, as in “finding flow” (Abuhamdeh & Csikszentmihalyi, 2012; Csikszentmihalyi, 1997; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000).

After having undertaken a review of the concept of inspiration from within the psychology literature, we propose that the nine characteristics of inspiration we have identified may be useful to the field of interpretation.

Discussion

Based on the literature review conducted, the benefits and characteristics of inspiration as described above seem to be directly relevant to interpretation. In this section, we will discuss how the nine characteristics of inspiration may be connected to the field of interpretation, including the practice of interpretation.

Inspiration is two-sided. This overarching characteristic of inspiration, i.e., the notion that inspiration involves both a trigger and a target, is well-suited for use in the interpretation field. The pedagogical literature aimed at improving the practice of interpretation is focused on helping visitors learn or connect to the meaning of the place (Beck & Cable, 2011; Ham, 1992, 2013; Widner-Ward & Wilkinson, 2006), and in inspiration-based terms, this existing literature is aimed at ensuring the visitors are inspired by and inspired to do or be something.

The trigger of inspiration in interpretation—what our visitors are most often inspired by—is usually the place. For example, Hart (1998) found that nature was the most common source of inspiration among his respondents, and this fits with interpretation’s sense of the site’s genius loci, or “spirit of the place.” There are many references to the importance of place in interpretation including Turek (2006), who advocated for place-based interpretation that connects audiences directly to the heritage resource, enabling them to hear site-specific stories and share in the work of meaning-making. In other examples showing the importance of place in interpretation, Hunter (2012b) studied sense of place in park interpretation and concluded that developing attachment to place may lead to re-inhabitation and preservation of place, while Van Matre (2008) eloquently refers to interpretation spaces as public jewels.

People are also a typical trigger of inspiration in interpretation and we assume that visitors will be inspired by interpreters and other staff they encounter at a site. This seems to be the premise the field of interpretation is built upon. For instance, Ham (2013) describes the role of interpreters as being provokers, teachers, and entertainers, with the provoker role being the most important one when making a difference is desired. In Applied Interpretation, Knapp devotes a section to the importance of the interpreter, noting that “the overall impression was virtually everyone interviewed in our research saw the interpreter as valuable and a positive aspect of their visit to the resource site” (2007, p. 110). And Edwards pointed out that, “an interpretation program can be no better that the interpreters in it” (1979, p. 38). In inspiration terms, these examples suggest that the visitors will be inspired by the interpreter. Studies into collective inspiration and social identity approaches suggest that investigations into ways visitors may be inspired by each other are also warranted. In The Participatory Museum, the author uses multiple examples to illustrate the value of visitors interacting within their group and between groups (Simon, 2010).

The target of inspiration, the inspired to side of inspiration, manifests in the interpretation field through interpreters and visitors being inspired to take action of some kind, e.g., either through being engaged in hands-on activities during a program or being encouraged to take actions after the program. In practice, participatory interpretation is increasingly being used, with visitors being encouraged to be more involved in the experience (McCarthy & Ciolfi, 2008; Simon, 2010; Tan, 2012). Interpreters are expected to leave their visitors with some kind of action to take after the interpretive experience, and the phrase “call to action” is now regularly used in interpretation practice (Hughes, 2011; Whatley, 2011). Tilden’s suggestion that “through interpretation, understanding; through understanding, appreciation; through appreciation, protection” (1977, p. 38), has led to interpretation in which the suggested actions are ones that will benefit the agency, such as not littering and not feeding wildlife. Converted to inspiration terminology, the end goal of interpretation would be seen as visitors being inspired to protect the resource.

However, research in non-interpretation fields has shown that Tilden’s programmatic sequence cannot be guaranteed, i.e., awareness of the need to care for a resource does not automatically transfer into actions to care for the resource (Bush-Gibson & Rinfret, 2010; Clover, 2002; Halpenny, 2010; Ham, 2013; Silberman, 2013; Uzzell & Ballantyne, 1998; Vaske & Kobrin, 2001). In inspiration terminology, this may reflect people being inspired to different ends than protection of the resource and it begs the question, would agencies commit to focusing on inspiration in interpretation if it means accepting that visitors may be inspired to take actions that the agency is not advocating or may not even consider acceptable?

The inspired-to-just-be concept that was mentioned briefly in the inspiration literature (Hart, 1993, 1998) is more vague, but may also be relevant to the interpretive field. For example, Van Matre’s work encourages participants in his camping programs to just sit and watch and be: “when you’re completely comfortable, take a couple of deep breaths and relax. As you breathe, settle into a state of motionless. Don’t move at all but don’t strain. Just relax. Let the natural world sweep over and engulf you” (1979, p. 189). Interpretation that encourages visitors to take no action, but instead to be mindful and reflective, as recommended by some authors (e.g., Langer, 1997; Markwell, Stevenson, & Rowe, 2004; Moscardo, 1996, 1999; Noh, 2014; Wong, 2013), warrants further consideration for the field of interpretation. Non-action may be just what many people need in order to slow down and connect with the place or idea and to reflect on its relevance to their lives.

Inspiration is transcendent. Interpretation may transcend the daily and inspire people to aha moments and peak experiences; to have such an impact is the hope, we would imagine, of all interpreters. The transcendence may exhibit itself in a passive response, i.e., an overall change in being, rather than a specific action, similar to Hart’s (1998) description of inspiration as either “form,” i.e., an action or creation, or “being,” i.e., our general state of existence. Interpretation may take people to a higher level of awareness or consciousness, although visitors are not likely to have a transcendent inspirational experience unless their basic human needs are taken care of first, as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs pointed out (1964, 1968). Interpreters leading guided tours or hikes know well the importance of pointing out the locations of the washrooms and water fountains prior to the event!

Inspiration is positive. Generally, interpretation is viewed by those participating in interpretive activities in a positive light and as having positive impacts. However, the positive nature of the term inspiration may be in contrast to the negative connotation often associated with the word provocation. Tilden’s fourth principle, “The chief aim of interpretation is not instruction but provocation,” has been a directive to the field for over 50 years and is well documented in Ham (2013). As described earlier, the word provocation is defined as “Action or speech that makes someone angry, especially deliberately”; it is a word indicating a challenge is posed to someone and while the challenge may be seen negatively, the end result may be seen to be positive. A conceptual exploration into our current understanding and use of the words provocation and inspiration in interpretation would be worthwhile.

As mentioned earlier, people seem to show gratitude towards the source of their inspiration (Thrash, Maruskin, et al., 2010) and as a positive notion, the concept of gratitude may be worth further exploration within the field of interpretation. Gratitude is an emotion that agencies offering interpretation would likely be interested in fostering in visitors. One future research question posed by Thrash, Maruskin, Cassidy, Fryer, & Ryan (2010) and relevant to interpretation would entail an investigation into which yields more gratitude, an intentional agent, such as an interpreter, or an unintentional agent such as nature, i.e., the place?

Inspiration is individual. Tilden’s first principle places the emphasis on relating to the visitor, and his sixth principle suggests that children’s interpretation should not be a dilution of an adult presentation (1977). Both these principles relate directly to the concept of inspiration being individual; we acknowledge that all visitors are inspired by different things and to different ends and that each visitor will make their own meaning of the place or idea being interpreted. Exploring this notion further fits with the movement towards more constructivist-based interpretation. For example, Staiff (2014) and others suggest that interpretation is a system of representation, i.e., the meaning of the object of heritage interpretation is not inherent in the resource or in the agency’s interpretation of it, but ultimately is the meaning of the personal experience in a place, with a person or creature or artifact. One role of interpretation is to help people find this meaning for themselves and to help make the place and/or its ideas relevant to their lives. Reminding ourselves that one approach will not fit all and offering a variety of interpretive experiences is one way to acknowledge that inspiration is individual.

Inspiration is unexpected. That inspiration is unexpected is ideally suited to interpretation, in which visitors may have aha moments or find that things just click into place at an unexpected moment. The exact moment when inspiration might occur for any of us is unknown and unknowable, and this makes life exciting! Perhaps interpretation in practice could benefit from greater attention to giving participants the unexpected in order to surprise and delight them. People can have inspirational experiences exploring tidepools; first-time visitors start seeing creatures of all sorts, creatures that they’ve never before seen and couldn’t even imagine seeing, all the while thinking they were just going to be looking, but not really expecting to be seeing anything interesting, in the pool. We can offer the unexpected through either personal or non-personal interpretation, and often, through careful planning, the experienced interpreter has planned for the unexpected; e.g., coming over a ridge with an extraordinary viewpoint, doing an evening program during the Perseid meteor shower, or planning on giving the visitor an unexpected but amazing experience with an artifact in a museum tour. Experiencing the unexpected is surely interpretation that aims to reach people at an emotional, far more than at a cognitive, level. For instance, in practice the authors have seen visitors thrilled to come upon something they were not expecting, such as a “games night” evening program, or an opportunity for the visitors to use costumes and props to tell their own stories. A recent study by Latham, Narayan, and Gorichanaz (2018) described the “surprising” influence of surprise and discovery on inspiration and noted that “an experience is more meaningful and memorable when it involves a ‘surprise’ or ‘flip’ experience” (p. 7).

Inspiration is holistic. Tilden’s fifth principle, i.e., that interpretation should aim to present a whole rather than a part, fits well with the psychological literature’s assertion that inspiration is holistic and “engages the head as well as the heart” (Thrash & Elliot, 2003, p. 878). Interpretation in the past has tended to focus on information first; however, within the field there is a shift occurring towards a more holistic perspective. For example, various authors have suggested that interpretation needs to engage visitors through more involvement, i.e., actions that would reach visitors in a more holistic and not simply cognitive way (Ballantyne & Packer, 2009; Ballantyne, Packer, & Sutherland, 2011; Blaney, 2013; Dierking, 1998; Falk & Dierking, 2000; Goldman, Chen, & Larsen, 2001; Goodrich & Bixler, 2012; Grenier, 2008; Hunter, 2012b, 2012a; Knapp & Benton, 2004; McCall & McCall, 1977; McCarthy & Ciolfi, 2008; Noh, 2014; Simon, 2010; Smith, 1999; Taylor & Caldarelli, 2004).

In addition, multiple authors also recommend inviting emotions into interpretation (Ballantyne, Packer, & Falk, 2011; Ballantyne et al., 2007; Hughes, 2012; Ingham, 2000; Latham, 2013; Martin, 2011; Smith, 1999; Wijeratne et al., 2014). Recognizing the importance of emotion in effective communication is nothing new: Aristotle’s formulation of rhetoric saw persuasive communications engaging with three kinds:

The first kind depends on the personal character of the speaker [ethos]; the second on putting the audience into a certain frame of mind [pathos]; the third on the proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself [logos]. Persuasion is achieved by the speaker’s personal character when the speech is so spoken as to make us think him credible. (Aristotle, Art of Rhetoric, 1356a 2,3)

Interpretation practice has seemingly focused on the first and the third parts of this rhetorical triangle, and in our quest to communicate agency messages, we’ve often missed the emotional connection that, as Aristotle notes, puts the audience into a certain frame of mind. In a holistic, inspiration-based approach to interpretation, the persuasive element of pathos would be given more attention, since emotion is a strong component of inspiration.

Inspiration is transmissible. As interpreters, we hope that the passion displayed in our interactions will lead to visitor inspiration. An unintended side effect of this interaction may be increased inspiration for the interpreter, which may set the wheels in motion for an ongoing cycle of inspiration where inspiring interpreters are inspired by inspiring places/artefacts/organisms/ ideas, as well as by inspiring visitors. This can lead to a virtuous cycle of reciprocal impact where our interpretive work is not the end experience, but simply one link in a journey of some of our audiences who are pursuing higher goals (Thrash & Elliot, 2004). The transmissibility of inspiration suggests that maintaining inspired interpreters is an important task for an agency. It is important that interpreters are given professional development opportunities, including the chance to spend more time in places of inspiration. And, as previously mentioned, since interpretation typically involves groups of participants; it would be beneficial to explore social interactions in interpretation as a source of inspiration; this may lead to the designing for provision of more socially-based experiences within interpretation, e.g., through dialogic interpretation. An Audience Centred Experience (ACE) approach to interpretation is being advocated by the US National Park Service (2018) and includes the use of participatory and dialogic techniques, including those espoused by the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience (2017). These new ideas fit well with the tenets of inspiration.

Inspiration requires receptivity. As already noted, some visitors will be more open to inspiration than others. Perhaps the visitors who choose to attend an interpretive event are already the ones most open to being inspired by the kinds of activities carried out there, while those who choose not to join in a program are inspired in different ways (Hood, 1983) and have different self-identities than those who don’t visit parks, museums, and galleries (Falk, 2012). Helping visitors and staff be receptive to being inspired is an ongoing and exciting challenge for the field.

Inspiration receptivity may be cultivated. This last characteristic of inspiration is particularly relevant to interpretation, as it seems that the job of the interpreter is to foster inspiration in visitors through cultivating an openness to what may potentially be new knowledge, experiences, emotions, ideas, or actions. How to develop programs that present the interpreter as a facilitator of inspiration and not merely a source of information is worthy of more attention, and different authors have advocated for interpreters to be facilitators of meaning making (Ashley, 2006; Dicks, 2000; Ham, 2013; Lück, 2003; Noh, 2014; Poria, Biran, & Reichel, 2009; Smith, 1999; Staiff, 2014). It would be interesting to explore how visitor receptivity to new ideas may be cultivated in interpretation and what may result from their inspiration. As previously mentioned, Thrash and Elliot (2003) developed an Inspiration Scale, and it would be an interesting challenge to modify this scale (or develop a new one) to look at the “inspirationality” of a particular person, place, or artefact as utilized in interpretive programming. The new work coming out of museum studies that looks at visitors’ preference for certain kinds of experiences may also hold promise. Pekarik and colleagues (2014) look at individual preferences for experiences that connect to Ideas, People, Objects, and Physical (known collectively as IPOP). Knowing more about our visitors and what kinds of experiences we might be able to offer that may inspire, perhaps in the context of the IPOP framework, should become an active domain of further research.

Conclusion

Upon completion of this exploration, we feel that giving consideration to the characteristics of inspiration gleaned from psychological studies would be useful to and productive in the field of heritage interpretation. It is also worth a reminder that no matter how we deconstruct the concept, we have to keep the whole in mind; inspiration as a concept is uplifting and compels us every day.

An investigation into the applicability of the characteristics of inspiration in the practice of interpretation could provide valuable insights for constructivist-based interpretation. We hope our contribution inspires readers to engage in dialogue about the concept and to undertake further exploratory research into how a focus on inspiration may help us continually improve our field in practice.

References

Abuhamdeh, S., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2012). Attentional involvement and intrinsic motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 36(1), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-011-9252-7

Ashley, S. (2006). Heritage institutions, resistance, and praxis. Canadian Journal of Communication, 31(3), 639–658. Retrieved from http://cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/viewArticle/1746

Ballantyne, R., & Packer, J. (2009). Introducing a fifth pedagogy: Experience based strategies for facilitating learning in natural environments. Environmental Education Research, 15 (March 2015), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802711282

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Falk, J. (2011). Visitors’ learning for environmental sustainability: Testing short- and long-term impacts of wildlife tourism experiences using structural equation modelling. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1243–1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.11.003

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., Hughes, K., & Dierking, L. (2007). Conservation learning in wildlife tourism settings: Lessons from research in zoos and aquariums. Environmental Education Research, 13 (March 2015), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701430604

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Sutherland, L. A. (2011). Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretive experiences. Tourism Management, 32, 770–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.012

Beck, L., & Cable, T. T. (2011). The gifts of interpretation for the 21st Century: Fifteen guiding principles for interpreting nature and culture. Urbana, IL: Sagamore Publishing.

Blaney, C. L. (2013). Dialogue programs tackle tough issues: Observations and interviews at three sites across the United States. Stephen F. Austin State University.

Brenneman, J. F. (2012). Purpose: Motivation or inspiration. Retrieved from http://archive.constantcontact.com/fs036/1101599026466/archive/1102934210710.html

Burgess, A. (1986). Homage to Qwert Yuiop: Selected journalism 1978–1985. London: Hutchinson.

Bush-Gibson, B., & Rinfret, S. R. (2010). Environmental adult learning and transformation in formal and nonformal settings. Journal of Transformative Education, 8(2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344611406736

Chadborn, D., & Reysen, S. (2016). Moved by the masses: a social identity perspective on inspiration. Current Psychology, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9545-9

Clover, D. E. (2002). Toward transformative learning: Ecological perspectives for adult education. In E. O’Sullivan, A. Morrell, & M. A. O’Connor (Eds.), Expanding the boundaries of transformative learning: Essays on theory and praxis (pp. 159–174). New York, NY: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145465

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow. Psychology Today, 30(4), 46–71. Retrieved from http://www.psychologytoday.com/

Davidson, P., & Black, R. (2007). Voices from the profession: Principles of successful guided cave interpretation. Journal of Interpretation Research, 12(2), 25–43. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Dicks, B. (2000). Encoding and decoding the people: Circuits of communication at a local heritage museum. European Journal of Communication, 15(1), 61–78. Retrieved from http://ejc.sagepub.com/content/15/1/61.short

Dierking, L. D. (1998). Interpretation as a social experience. In D. Uzzell & R. Ballantyne (Eds.), Contemporary issues in heritage and environmental interpretation: Problems and prospects (pp. 56–76). London, England: The Stationery Office.

Edwards, Y., & Solman, V. E. F. (1979). The land speaks: Organizing and running an interpretation system. Toronto, ON: The National and Provincial Parks Association of Canada.

Engen, B. C. (2005). The experience of creative inspiration among creative professionals: A grounded theory approach. San Francisco, California Institute of Integral Studies.

Falk, J. H. (2012). Identity and the museum visitor experience. London: Routledge.

Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (2000). Learning from museums: Visitor experiences and the making of meaning. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Fink, A. (2010). Conducting research literature reviews: From the internet to paper. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Fredrickson, L. M., & Anderson, D. H. (1999). A qualitative exploration of the wilderness experience as a source of spiritual inspiration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19, 21–39. https://doi.org/0272-4944/99/010021+19

Goldman, T. L., Chen, W.-L. J., & Larsen, D. L. (2001). Clicking the icon: Exploring the meanings visitors attach to three national capital memorials. Journal of Interpretation Research, 6(1), 3–30. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Gonzalez, S. P., Metzler, J. N., & Newton, M. (2011). The influence of a simulated “pep talk” on athlete inspiration, situational motivation, and emotion. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 6(3), 445–459. Retrieved from http://www.multi-science.co.uk/sports-science&coaching.htm

Goodrich, J. L., & Bixler, R. D. (2012). Getting campers to interpretive programs: Understanding constraints to participation. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17(1), 60–70. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Gotz, I. (1998). On inspiration. Cross Currents, 48(4), 510. Retrieved from http://www.crosscurrents.org/

Government of Canada. (2013). Parks Canada home page. Retrieved from http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/index.aspx

Grenier, R. (2008). Practicing what we preach: A case study of two training programs. Journal of Interpretation Research, 13(1), 7–25. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Haidt, J. (2000). The positive emotion of elevation. Prevention and Treatment, 3, 1–5.

Halpenny, E. A. (2010). Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 109–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.006

Ham, S. H. (1992). Environmental interpretation: A practical guide for people with big ideas and small budgets. Golden, CO: North American Press.

Ham, S. H. (2013). Interpretation: Making a difference on purpose. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Hart, T. R. (1993). Inspiration: An exploration of the experience and its role in healthy functioning. University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Retrieved from http://www.worldcat.org/

Hart, T. R. (1998). Inspiration: Exploring the experience and its meaning. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 38(3), 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167890383002

Hart, T. R. (2004). Opening the contemplative mind in the classroom. Journal of Transformative Education, 2(28), 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344603259311

Haslam, S. A., Reicher, S. D., & Platow, M. (2011). The new psychology of leadership: Identity, influence, and power. Hove, East Sussex, UK: Psychology Press.

Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Leavy, P. (2011). The practice of qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Hood, M. G. (1983). Staying away: Why people choose not to visit museums. Museum News, April, 50–57.

Hughes, K. (2011). Designing post-visit action resources for families visiting wildlife tourism sites. Visitor Studies, 14(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2011.557630

Hughes, K. (2012). Measuring the impact of viewing wildlife: Do positive intentions equate to long-term changes in conservation behaviour? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, (March 2015), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.681788

Hunter, J. (2012a). A pedagogy of emplacement: Experiential storytelling and sense of place education in park interpretive programs. Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/35/09/3509923.html

Hunter, J. (2012b). Towards a cultural analysis: The need for ethnography in interpretation research. Journal of Interpretation Research, 17(2), 47–58. Retrieved from www.interpnet.com

Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3–10.

Ingham, Z. (2000). Rhetoric of disengagement: Interpretive talks in the national parks. In N. W. Coppola & B. Karis (Eds.), Technical communication, deliberative rhetoric, and environmental discourse: Connections and directions (pp. 139–148). Stamford, CN: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. (2017). Home page. Retrieved from https://www.sitesofconscience.org/en/home/

Jackson, B. (2012). Give your people a cause and inspiration will follow: The secrets of successful team-building. Human Resource Management International Digest, 20(2), 32–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/09670731211208184

Jennings, D. J. I. (2012). Inspiration: Examining its emotional correlates and relationship to internalized values. Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia. Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/35/49/3549626.html

Knapp, D. (2007). Applied interpretation: Putting research into practice. Fort Collins, CO: National Association for Interpretation.

Knapp, D., & Benton, G. M. (2004). Elements to successful interpretation: A multiple case study of five national parks. Journal of Interpretation Research, 9(2), 9–25. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Knapp, D., & Forist, B. (2014). A new interpretive pedagogy. Journal of Interpretation Research, 19(1), 33–38. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Kwall, R. R. (2006). Inspiration and innovation: The intrinsic dimension of the artistic soul. Notre Dame Law Review, 81(5), 1–11. Retrieved from http://ndlawreview.org/

Langer, E. J. (1997). The power of mindful learning. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books Group.

LaPage, W. (2001). Nature “speaks”: Exploring the inspiration of public parklands. Legacy (National Association for Interpretation), (Sept-Oct), 18–23.

LaPage, W. (2002). Interpretation and the eureka moment. Journal of Interpretation Research, 7(1), 25–29. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Latham, K. F., Narayan, B., & Gorichanaz, T. (2018). Encountering the muse: An exploration of the relationship between inspiration and information in the museum context. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 1–10.

Latham, K. F. (2013). Numinous experiences with museum objects. Visitor Studies, 16(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2013.767728

Lück, M. (2003). Education on marine mammal tours as agent for conservation: But do tourists want to be educated? Ocean & Coastal Management, 46(9–10), 943–956. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0964-5691(03)00071-1

Markwell, K., Stevenson, D., & Rowe, D. (2004). Footsteps and memories: Interpreting an Australian urban landscape through thematic walking tours. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 10(5), 457–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/1352725042000299063

Martin, C. (2011). Hearts first- then minds. InterpScan (Interpretation Canada), 33(3), 3–5. Retrieved from http://www.interpscan.ca/

Maslow, A. H. (1964). Religions, values, and peak experiences. London: Penguin Books Limited.

Maslow, A. H. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

McCall, J. R., & McCall, V. (1977). Outdoor recreation: Forest, park and wilderness. Beverly Hills, CA: Benziger Bruce and Glencoe.

McCarthy, J., & Ciolfi, L. (2008). Place as dialogue: Understanding and supporting the museum experience. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 14(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250801953736

Mills, E. A. (2001). Adventures of a nature guide. Long Peak, CO: Temporal Mechanical Press.

Milyavskaya, M., Ianakieva, I., Foxen-Craft, E., Colantuoni, A., & Koestner, R. (2012). Inspired to get there: The effects of trait and goal inspiration on goal progress. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(1), 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.031

Mitchell, K. (2005). “The soul of things:” Spirituality and interpretation in national parks. Epoche: The University of California Journal for the Study of Religion, 23(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/Retrieved from http://www.epoche.ucsb.edu/

Montuori, A. (2011). Beyond postnormal times: The future of creativity and the creativity of the future. Futures, 43, 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2010.10.013

Moscardo, G. (1996). Mindful visitors: Heritage and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 376–397. https://doi.org/0160-7383 (95) 00068-2

Moscardo, G. (1999). Making visitors mindful: Principles for creating sustainable visitor experiences through effective communication. Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing.

National Association for Interpretation. (2014). Mission, Vision, and Core Values. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/NAI/interp/About/What_We_Believe/nai/_About/Mission_Vision_and_Core_Values.aspx?hkey=ef5896dc-53e4-4dbb-929e-96d45bdb1cc1-

Noh, E. J. (2014). Constructs and mechanisms of personally-delivered interpretive programs that lead to mindfulness and meaning-making. Michigan State University. Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/36/17/3617369.html

O’Grady, K., & Richards, P. S. (2011). The role of inspiration in scientific scholarship and discovery: Views of theistic scientists. Explore, 7(6), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2011.08.004

Oxford University Press. (2000). Definition of inspiration. Retrieved from http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.royalroads.ca/view/Entry/96980?redirectedFrom=inspiration#eid

Oxford University Press. (2019a). Definition of Mind Map. Retrieved March 17, 2019, from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/mind_map

Oxford University Press. (2019b). Definition of Provocation. Retrieved March 17, 2019, from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/provocation

Pekarik, A. J., Schreiber, J. B., Hanemann, N., Richmond, K., & Mogel, B. (2014). A theory of experience preference: IPOP. Curator: The Museum Journal, 57(1), 5–27.

Pessoa, L. (2008). On the relationship between emotion and cognition. Nature Neuroscience, 9, 148–158.

Poria, Y., Biran, A., & Reichel, A. (2009). Visitors’ preferences for interpretation at heritage sites. Journal of Travel Research, 48(1), 92–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287508328657

Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037//003.066X.55.1.5

Shalaginova, I. (2012). Understanding heritage: A constructivist approach to heritage interpretation as a mechanism for understanding heritage sites. Brandenburg University of Technology.

Shiota, M. N., Thrash, T. M., Danvers, A. F., & Dombrowski, J. T. (2017). Transcending the self: Awe, elevation, and inspiration. In & L. D. K. M. M. Tugade, M. N. Shiota (Ed.), Handbook of positive emotions. Guilford Press.

Silberman, N. A. (2013). Heritage interpretation as public discourse: Towards a new paradigm. In B. Rudolph (Ed.), Understanding heritage: Paradigms in heritage studies. Paris, France: UNESCO.

Simon, N. (2010). The participatory museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0.

Simopoulos, J. C. (1948). The study of inspiration. The Journal of Philosophy, 45(2), 29–41. Retrieved from http://www.journalofphilosophy.org/

Smith, J. G. (1999). Learning from popular culture: Interpretation, visitors and critique. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 5(3–4), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527259908722260

Staiff, R. (2014). Re-imagining heritage interpretation: Enchanting the past-future. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Tan, L. (2012). The participatory museum. Museum Management and Curatorship, 27(2), 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2012.674675

Taylor, E. W., & Caldarelli, M. (2004). Teaching beliefs of non-formal environmental educators: A perspective from state and local parks in the United States. Environmental Education Research, 10(4), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462042000291001

Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2003). Inspiration as a psychological construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 871–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.871

Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2004). Inspiration: Core characteristics, component processes, antecedents, and function. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 87(6), 957–973. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.957

Thrash, T. M., Elliot, A. J., Maruskin, L. A., & Cassidy, S. E. (2010). Inspiration and the promotion of well-being: Tests of causality and mediation. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology, 98(3), 488–506. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017906

Thrash, T. M., Maruskin, L. A., Cassidy, S. E., Fryer, J. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Mediating between the muse and the masses: Inspiration and the actualization of creative ideas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 469–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017907

Thrash, T. M., Moldovan, E. G., Oleynick, V. C., & Markusin, L. A. (2014). The psychology of inspiration. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8/9, 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12127

Tilden, F. (1977). Interpreting our heritage. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Turek, E. M. (2006). Form follows function: Interpretive wisdom for environmental educators. Journal of Interpretation Research, 11(2), 47–51. Retrieved from http://www.interpnet.com/

Turner, J. C. (1975). Social comparison and social identity: Some prospects for intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology and Marketing, 5(1), 1–34.

US National Park Service. (2009). Denali National Park and Preserve education plan. Washington: US Department of the Interior. Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/dena/parkmgmt/ed-plan.htm

US National Park Service. (2018). Interpretive Skills: 21st Century National Park Service. Retrieved from https://mylearning.nps.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Foundations-of-Interpretation-v.2016.pdf

Uzzell, D., & Ballantyne, R. (1998). Contemporary issues in heritage and environmental interpretation: Problems and prospects. London, England: The Stationery Office.

Van Matre, S. (1979). Sunship Earth. Martinsville, IN: American Camping Association.

Van Matre, S. (2008). Interpretive design and the dance of experience. Greenville, WV: The Institute for Earth Education.

Vaske, J. J., & Kobrin, K. C. (2001). Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of Environmental Education, 32(4), 16–21. https://doi.org/dx.doi.org/10.1080/0095896019598658

Whatley, M. E. (2011). Interpretive solutions: Harnessing the power of interpretation to help resolve critical resource issues. US National Park Service.

Widner Ward, C., & Wilkinson, A. E. (2006). Conducting meaningful interpretation: A field guide for success. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing.

Wijeratne, A. J. C., Van Dijk, P. a., Kirk-Brown, A., & Frost, L. (2014). Rules of engagement: The role of emotional display rules in delivering conservation interpretation in a zoo-based tourism context. Tourism Management, 42, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.11.012

Williams, K., & Harvey, D. (2001). Transcendent experience in forest environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(3), 249-260. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0204

Wong, C. U. I. (2013). The sanitization of colonial history: Authenticity, heritage interpretation and the case of Macau’s tour guides. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(6), 915–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.790390